In the closing phase of World War II, the rules outlined in the Geneva Convention were increasingly set aside. In newly occupied regions of Germany, many surrendered troops were deliberately not granted official prisoner-of-war status, a decision that allowed Allied forces to bypass the usual legal and humanitarian requirements associated with POW treatment.

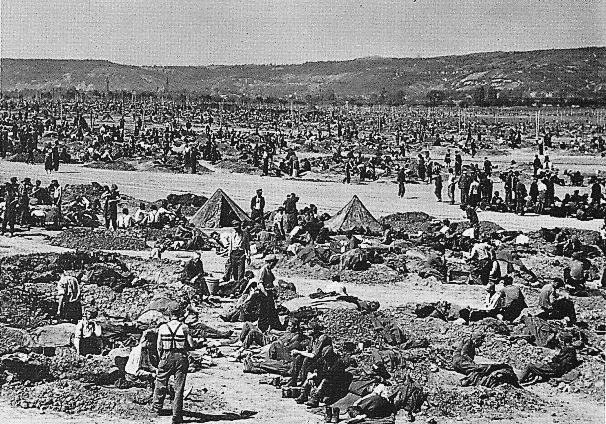

Consequently, large holding sites sprang up throughout western Germany. These improvised detention areas—collectively called the Rheinwiesenlager, or Prisoner of War Temporary Enclosures (PWTE)—confined hundreds of thousands of German servicemen. Severe overcrowding, inadequate sanitation, and shortages of basic necessities made conditions extremely difficult as the conflict came to an end.

Even with their enormous scale and human toll, the Rheinwiesenlager have faded into relative obscurity in the narrative of Europe’s postwar period.

Allied success in Europe following the D-Day landings

After the success of D-Day, Allied forces pushed through occupied areas and into Germany. Although they met some resistance, many German soldiers surrendered, and the Allies became responsible for housing and caring for them.

At first, both British and American forces shared this responsibility. But by early 1945, the British refused to accept new prisoners due to limited space in their camps. This left the Americans with the full responsibility of handling the increasing number of POWs as the war continued.

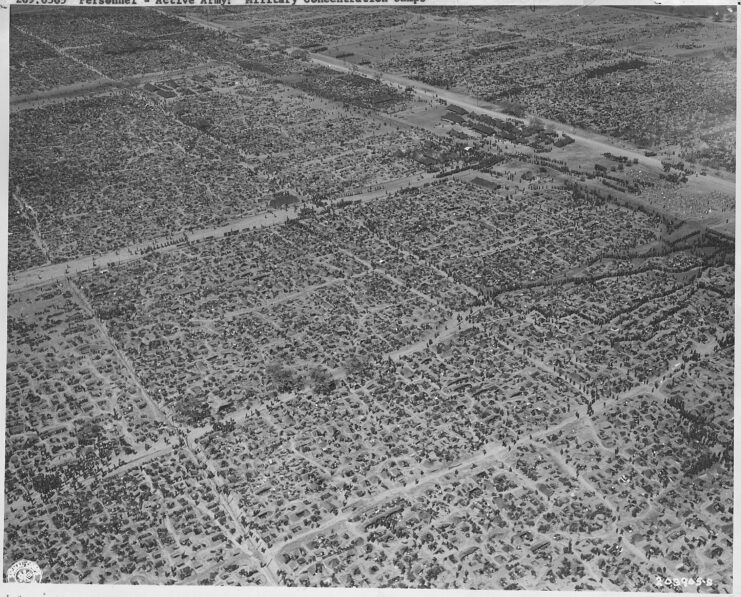

To manage the growing number of captives, the U.S. Army set up the Rheinwiesenlager—a group of prison camps located throughout Allied-occupied Germany. These camps began operating in April 1945 and became even more important after Germany’s surrender in May, helping prevent any possible uprisings during the early days of the occupation.

Layout of the Rheinwiesenlager

The Rheinwiesenlager camps were established on farmland in western Germany under Allied control, strategically positioned near rail lines to facilitate prisoner transport. Each camp was fenced with barbed wire and divided into sections designed for 5,000-10,000 people. In practice, however, populations quickly exceeded these capacities, with some camps swelling to over 100,000 prisoners. Overall, estimates suggest that between 1 and 1.9 million individuals passed through the Rheinwiesenlager system.

Most of those interned were regular Wehrmacht soldiers who had surrendered at the war’s end. Higher-ranking officers, SS members, and other prominent figures were typically removed from these camps and sent elsewhere for interrogation, prosecution, or further investigation.

There were no shelters for living quarters

Inside the Rheinwiesenlager, prisoners were largely responsible for their own survival. With little hands-on oversight, they organized work details, tended to the wounded and ill, and stretched the meager food rations as far as possible. A handful of detainees were appointed to uphold camp rules and keep order—duties that occasionally came with the small advantage of slightly larger rations. Although separate sections existed for cooking, medical treatment, and administrative tasks, these facilities could not be used as living spaces. Most men were forced to build their own shelter, scraping out shallow dugouts or fashioning makeshift coverings from whatever scraps they could find. Exposed to weather and lacking even basic necessities, daily life demanded constant ingenuity and sheer resilience.

Disarmed Enemy Forces (DEFs)

The harsh conditions faced by these prisoners, reflected in their crude outdoor shelters, highlighted the severe treatment they received from their captors. This treatment was allowed because they were designated as Disarmed Enemy Forces (DEFs) rather than prisoners of war (POWs).

Before the Rheinwiesenlager camps were created, Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower introduced this new classification, stripping away the protections guaranteed to POWs under the Geneva Convention on Prisoners of War (1929). American forces defended this decision by asserting that these individuals belonged to a state that no longer existed, thereby justifying alternative forms of mistreatment.

Was the inhumane treatment intentional?

Under this classification, authorities could “legally” block Red Cross visits and withhold humanitarian aid. The Geneva Convention was specifically designed to prevent the abuse of POWs, but without its protections, DEFs were exposed to mistreatment with little accountability for their captors.

These events have led many to view the actions of Eisenhower and those in charge of the Rheinwiesenlager as intentional acts of inhumane treatment.

Rheinwiesenlager conditions

Overall, the conditions in the Rheinwiesenlager were horrific.

Historian Stephen Ambrose investigated many claims made about the camps, and concluded, “Men were beaten, denied water, forced to live in open camps without shelter, given inadequate food rations and inadequate medical care. Their mail was withheld. In some cases prisoners made a ‘soup’ of water and grass in order to deal with their hunger.”

Begging for more food wasn’t an option either, as those prisoners were often shot as “escapees,” should they have gotten near the barbed wire fences. Reports also claim locals would be shot if they tried to provide aid to the POWs.

Legacy of the Rheinwiesenlager

Given the living conditions of the Disarmed Enemy Forces, it’s no wonder the death toll was high. However, because they weren’t officially known as prisoners of war, few records were kept. Instead, many Germans would simply go missing from roll call, never to be seen again.

Due to the lack of records, death estimates vary, depending on who you ask. The official statistics from the US Army state that around 3,000 people died while in the Rheinwiesenlager. German estimates, however, provide a figure of 4,537.

James Bacque, the author of Other Losses: An Investigation Into the Mass Deaths of German Prisoners at the Hands of the French and Americans After World War II, alleges the number is between 100,000 and one million. However, his claims have been discredited by his peers.

More from us: The Battle of Cologne Saw a Legendary Standoff Between a Panther and a Pershing

Regardless of the overall death toll, the treatment of DEFs has been heavily criticized, despite it going largely unnoticed in more recent years. Many have pointed out that the Americans violated a host of international laws on the treatment of prisoners, even though they weren’t classified as POWs, particularly in their feeding – or lack thereof.p