The fall of France to German invasion in 1940 put the British in an uncomfortable position. It led to one of Great Britain’s most controversial actions of the war – an attack against the French fleet.

The Importance of the French Fleet

Control of the seas was vital to Great Britain. Without it, she would not be able to import vital food and industrial materials or defend her coast against German invasion.

In June 1940, France was on the verge of surrender to Germany. The French army was in ruins but her navy was still intact. If it fell into German hands, it would more than double the power of the German fleet.

With control of naval bases on the French west coast and in North Africa, Germany would be able to control the Mediterranean and compete with the British for dominance in the Atlantic.

The British watched tensely, waiting to see what would happen.

The Navy and the Armistice

Mid-June saw a series of tense negotiations, not all of them between the French and the Germans. Pro- and anti-surrender factions were vying for control of the French government. French representatives were negotiating with their British allies about the conditions under which they could surrender.

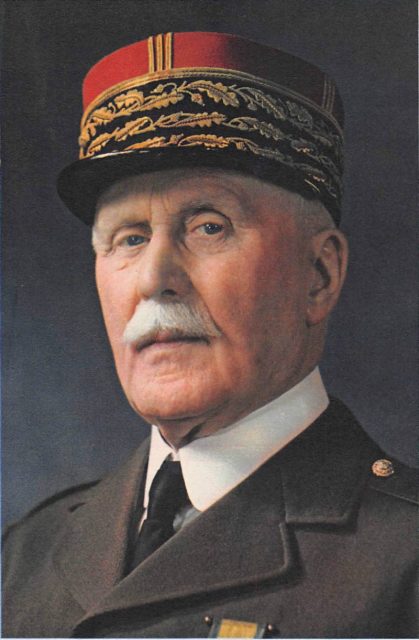

The British said that they would accept a French surrender as long as the French fleets first sailed to British ports. But elements in the French government more favorable to the Nazis, led by General Pétain, gained dominance in the internal negotiations.

The French agreed to surrender with their ships still in French-controlled ports. There, the ships would be allowed to disarm, taking them out of action.

An Uncomfortable Operation

The British did not know about this last condition. Even if they had known, they could not have trusted the Germans not to seize the fully armed ships once the surrender was complete. Hitler had repeatedly shown that his word meant nothing, even when it was part of a formal treaty.

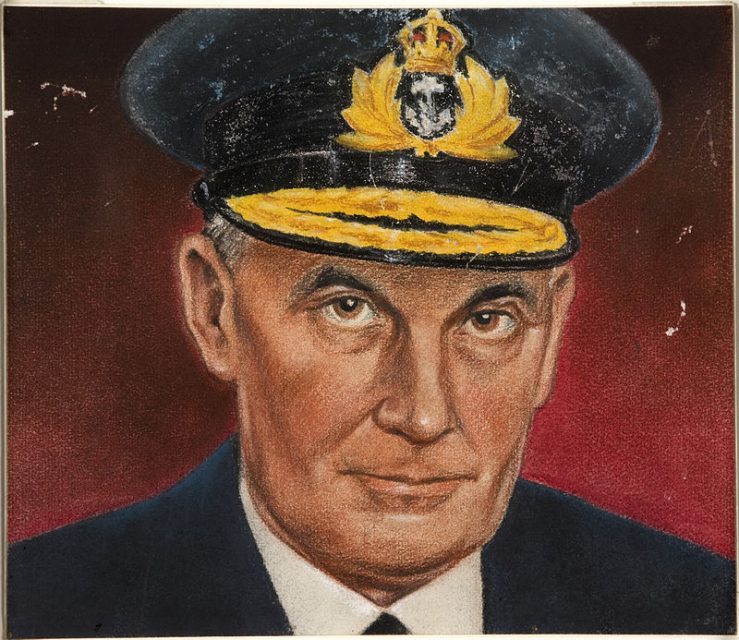

British politicians decided that they had to stop the Germans from getting these ships, by force if necessary. On June 28, a newly formed naval formation called Force H and led by Vice-Admiral Sir James Somerville set out to enforce the government’s will.

It was an uncomfortable operation for Somerville and his men. Weeks before, the French had been their allies, fighting together against a common cause. They would prefer almost any other option to attacking them.

Stand-Off at Oran

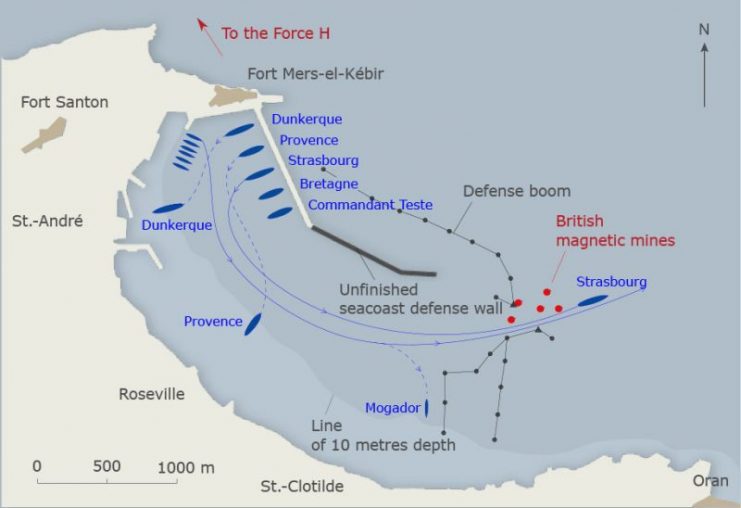

By now, a large part of the French fleet was in harbor at Oran in Algeria and the nearby naval base of Mers el Kébir. Somerville sent Captain Holland, former British naval attaché in Paris, to negotiate with the French Admiral Gensoul, to try to arrange his surrender.

As the negotiations progressed, tensions rose. The British mined the harbor mouth to prevent a French escape, aggravating Gensoul. Then British intelligence intercepted a message summoning reinforcements to help the French.

Late in the afternoon on July 3, negotiations ended. Somerville informed Gensoul that unless the French agreed to his terms, he would attack. Holland returned to the British fleet.

Talking had failed.

Opening Fire

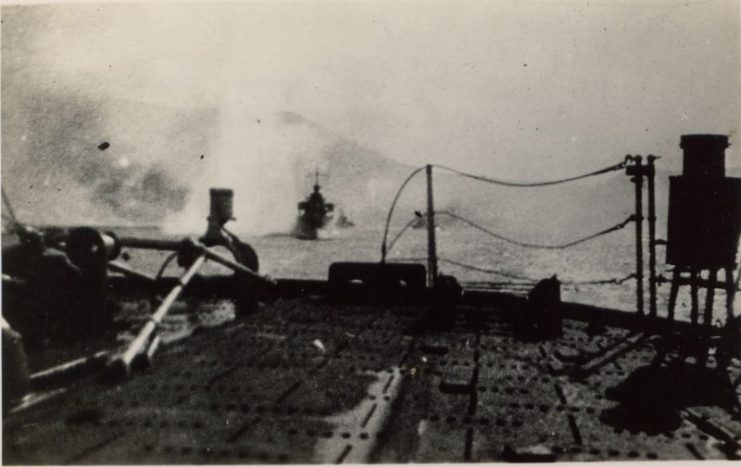

Just before six in the evening, the British opened fire.

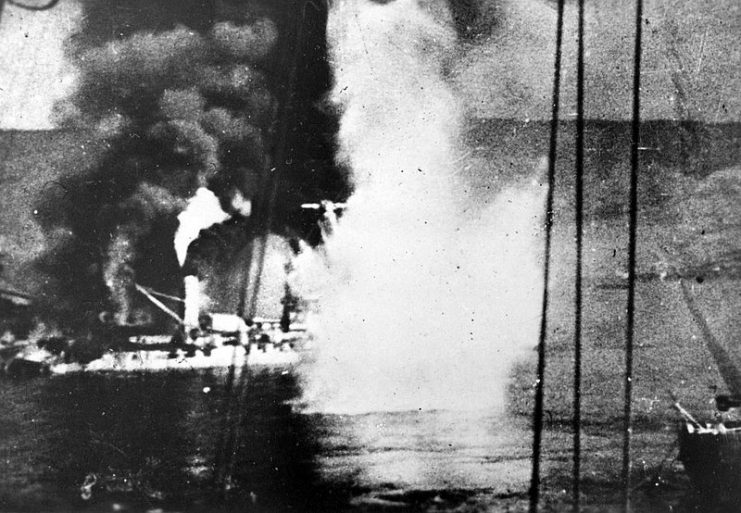

Caught in the harbor, the French struggled to avoid their fate. As they rushed to get moving and out to sea, British shells came screaming down on them.

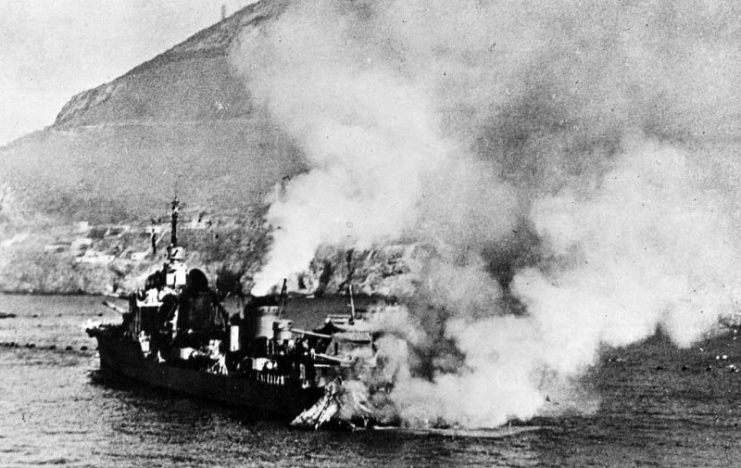

The battleship Bretagne was torn open by a huge explosion, capsized, and sank. Several other ships were badly damaged and over a thousand men killed, while the British fleet was almost entirely unscathed.

Dodging the mines in the harbor entrance, several French ships managed to escape. Others were forced to run aground.

In Great Britain

Meanwhile, back in Great Britain, a different sort of operation was underway.

Before dawn on July 3, armed parties from the Royal Navy boarded French warships in Portsmouth and Plymouth. They seized control of the ships rather than risk relying on the loyalties of the French crews.

There were few casualties – one French officer killed and two British wounded. Some of the French crewmen joined the Free French forces assembling in Great Britain, but most were sent to internment camps, adding to growing resentment at the behavior of their supposed allies.

Further Attacks

Over the following days, Force H carried out more attacks against French ships in North Africa. An aerial attack at Mers el Kébir badly damaged Gensoul’s flagship, the Dunkerque, putting her out of action for a year. A similar attack at Dakar crippled the battleship Richelieu, which also took a year to repair.

Alexandria – Avoiding Bloodshed

At Alexandria, events played out very differently. Here, the French and British squadrons had worked together and there were good relations between their officers. Vice-Admiral Godfroy, the British commander, wanted to avoid bloodshed. He also feared that sinking the French ships would block the harbor.

At first, the French agreed not to leave the harbor. But the attack at Oran undermined that deal, leading to several days of tense negotiations. The French considered heading out to sea, but Godfroy managed to talk them out of it. He sent British officers to appeal directly to the French crews, winning them over.

On July 7, an agreement was reached. The British agreed not to use force. In return, the French would de-fuel and disarm their ships.

Aftermath

The attack on the French fleet, together with the internment of their crews in Great Britain, embittered many French people against the British and hardened the resolve of collaborators to join the Germans.

It also led to a distrust that would cause problems when Allied forces invaded French North Africa in 1942. And on a simpler level, the Allies had lost men and ships that might have fought for them.

Read another story from us: The Start of the BIG campaigns 73,000 Strong – Operation Torch

Alexandria showed that force could have been avoided at Oran, as did later actions by French captains. But for Somerville, the fate of his nation was at stake, and he didn’t have the benefit of hindsight. His decision now looks like the wrong one, but amid the tensions of those terrible days, with the forces of Fascism swarming across Europe, it was understandable.