Around the U.S., and around many nations across the world, there are monuments to WWII collaborators, and to people who directly committed terrible acts against humanity. Why do these exist? Why are they celebrated, despite what we now know? As always with history, its much more complex than it first appears.

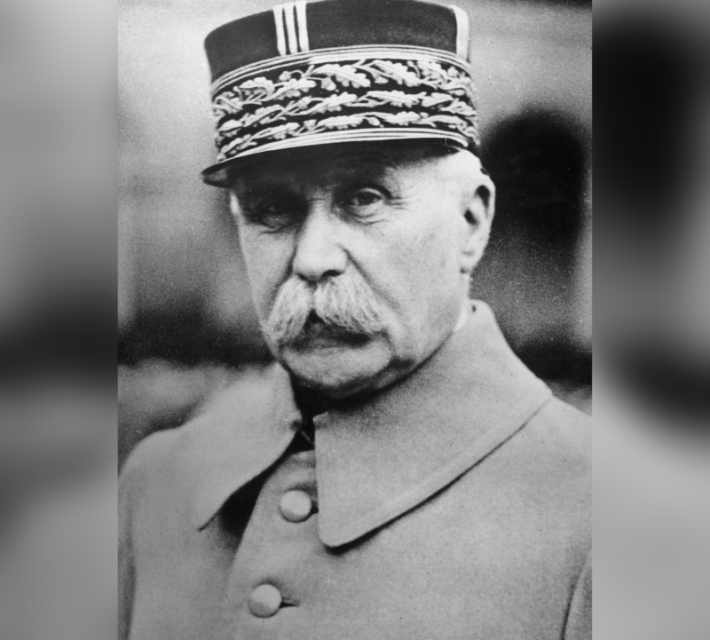

Philippe Pétain: WWI hero, WWII collaborator

On Broadway, in New York City, there is a plaque honoring Philippe Pétain, who lived from 1856 to 1951. Pétain was the leader of the Vichy government, an authoritarian state and ally of the Third Reich after the fall of France in 1940. France would be completely controlled by Nazi Germany by 1942. During his time as the head of this government, Pétain helped establish anti-Semitic and anti-Bolshevik attitudes.

Pétain approved anti-Semitic laws that allowed the deportation of 76,000 Jews to concentration camps around Europe, most of whom went to Auschwitz. He agreed with much of the Nazis’ ideology and even met with Hitler himself.

This paints a simple picture of Pétain, that he is one of history’s bad guys and one not to be celebrated. So why does he have a plaque dedicated to him in New York? Why would there ever be monuments to WWII collaborators?

As mentioned, it’s complicated.

Before the chaos of WWII tore through Europe, Pétain was a hero. He had been appointed Commander in Chief and restored the French Army’s confidence, leading them to victory at the Battle of Verdun.

This earned him a ticker-tape parade in New York in 1931, which his plaque on Broadway, placed in 2004, was meant to remember. It is therefore hard to write off a historical figure with such a complex life, who was both a celebrated hero in one war, and a man who supported one of the world’s most deplorable ideologies in another.

Streets named after Pétain in France have slowly been removed, but Parisian plans to memorialize him once again were raised in 2018, before being quickly shut down after international protest.

Adolfas Ramanauskas, anti-Soviet resistance fighter with a checkered past

More recently, a memorial to Adolfas Ramanauskas, a Lithuanian resistance member, was erected in Chicago, sparking controversy over the life of who it was dedicated to. Ramanauskas was a prominent member of the Lithuanian resistance against the Soviet Union’s occupation of the country after WWII. He climbed the ranks, eventually becoming the chairman of the Union of Lithuanian Freedom Fighters.

Living a life on the run, he was eventually captured and executed by the KGB. Since then, he has been regarded as a national hero.

However, like Pétain, Ramanauskas is not without controversy. It is believed that he was a prominent member of the Latvian Activist Front, a group that had anti-Semitic views, in the early days of the Nazi occupation of Lithuania. It is claimed that Ramanauskas led a gang of vigilantes that actively persecuted the Jewish community.

At the time of the Nazi invasion, there were around 220,000 Jews living in Lithuania. Just a few months later, there were only 40,000 left.

After the announcement of the memorial, it received significant push-back, especially from Russia, which claims the memorial is insulting, in part due to its unveiling date landing in close proximity to the Holocaust Remembrance Day.

Video: A museum to disgraced monuments

The Lithuanian government insists that the claims are baseless, as there isn’t any evidence Ramanauskas actually killed anybody. They also insist that the claims date back to Soviet propaganda from the 1950s.

The Jewish human rights organization the Simon Wiesenthal Center has voiced its opinion on the matter, agreeing that while there isn’t any evidence that he directly participated in the killing, Ramanauskas himself has admitted to his involvement in the group in his own memoirs.

The Wiesenthal Center also referenced the case of Jonas Noreika, another Lithuanian who was executed by the Soviets and elevated to the rank of a national hero, before his granddaughter revealed he was a Nazi collaborator who had done “monstrous things.”

More from us: Why Did the French Army Collapse So Quickly? – Omnibooks Magazine, 1942

Just with these two cases, it’s quite clear to see that while on the surface the answer may seem obvious, once the layers are peeled back, a far more complex story emerges. This often clouds our expectations of historical figures, who we often assume must either be good or bad, without considering that they may be both.

Should monuments to WWII collaborators exist? And is there a way to memorialize what good these historical figures might have done without seeming to celebrate their terrible deeds?