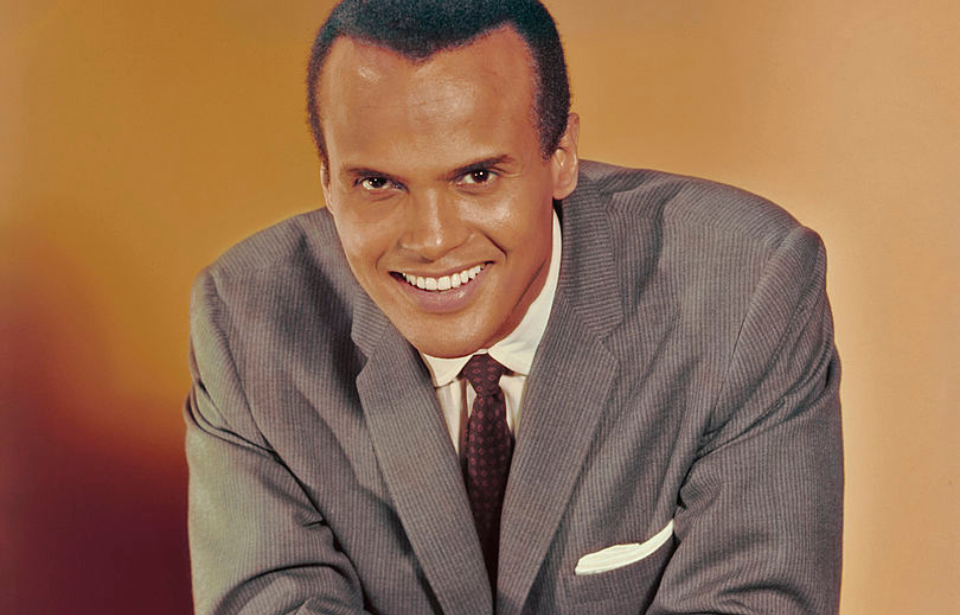

Harry Belafonte passed away in April 2023, ending a decades-spanning career that forever changed the faces of music, cinema and activism. Prior to becoming a household name, the famed calypso singer served in the US Navy. Enlisting in 1944, he was assigned to Port Chicago shortly after the base saw one of the worst disasters to occur in the United States during World War II.

Harry Belafonte grew up in poverty

Harold “Harry” Belafonte was born on March 1, 1927 to a chef father and a housekeeper mother. Growing up, the former was hardly in the picture, meaning Belafonte and his little brother were technically raised by a single mom. He resided in Harlem during the Great Depression, describing this time in his life as one of poverty.

Between 1932-40, Belafonte lived in Jamaica with one of his grandmothers. During this time, he attended Wolmer’s Schools.

Narrowly avoiding the Port Chicago Disaster

Upon returning to the US, Harry Belafonte attended George Washington High School, in New York City. While in his mid-teens, he watched the World War II-era propaganda film, Sahara (1943), which prompted him to leave school and enlist in the US Navy. It was just one day after his 17th birthday.

The US military wasn’t a kind place for African Americans at the time Belafonte enlisted; Black servicemen faced institutionalized racism. Members of the Navy, in particular, were relegated to support roles, rather than deployed overseas. Belafonte received the same treatment and was assigned to Port Chicago, just a few miles from San Francisco.

The future singer arrived at the base shortly after the Port Chicago Disaster. On July 14, 1944, a large explosion occurred while the SS Quinault Victory and E.A. Bryan were being loaded with munitions. Of the 320 killed that day, two-thirds were Black. Another 390 individuals were injured. The total is believed to account for 15 percent of African American casualties during the war.

Following the disaster, 328 ordnance battalion sailors refused to return to work until conditions at Port Chicago improved. Fifty of them were court-martialed and charged with mutiny. They were convicted and sentenced to 15 years in prison and hard labor, on top of receiving a dishonorable discharge. All 50 men were released in 1946, following the end of the conflict.

Belafonte later spoke out about how the sailors – dubbed the “Port Chicago 50” – were treated, saying, “It was the worst homefront disaster of World War II, but almost no one knows about it or what followed.” He added, “The Port Chicago mutiny was one of America’s ugliest miscarriages of justice, the largest mass trial in naval history, and a national disgrace.”

Of his 18 months of service, Belafonte spent two weeks in the naval prison in Portsmouth, Virginia for minor offenses. During this time, he saw German prisoners of war (POWs) being treated better than Black service members, a sight that “sickened” him and led him to become “radicalized,” politically.

Harry Belafonte used his GI Bill benefits to kickstart his career

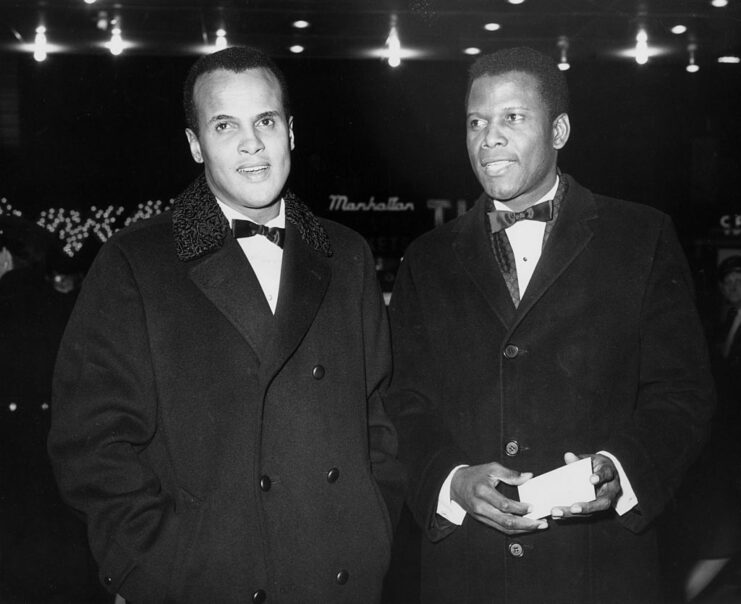

Throughout the 1940s, Harry Belafonte worked as a janitor’s assistant. One day, a tenant gave him two tickets to the American Negro Theatre as a tip, prompting him to attend a show. He fell in love with the medium, and even met and befriend future Academy Award-winning actor Sidney Poitier.

Toward the end of the decade, Belafonte used his benefits under the GI Bill to attend acting classes at New York City’s The New School. Among his classmates were Poitier, Bea Arthur, Tony Curtis, Marlon Brando and Walter Matthau. He also performed at the American Negro Theatre during this time.

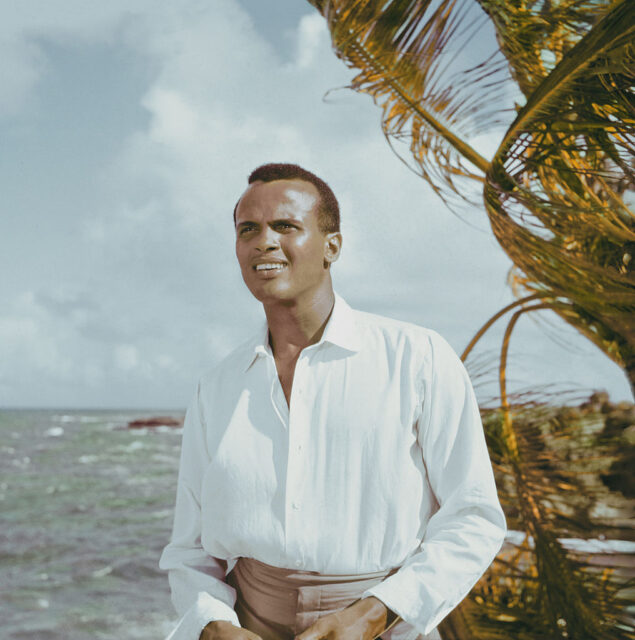

Becoming the ‘King of Calypso’

Harry Belafonte began his music career as a club singer in New York City, at one point being backed by the Charlie Parker Band. He signed his first record deal in 1949, and three years later joined RCA Victor’s roster. It was under this label that he released the majority of his music, including the crowd favorite “Matilda.”

While building his music career, Belafonte continued to act, winning a Tony Award for his appearance in the 1954 Broadway revue, John Murray Anderson’s Almanac. Two years later, he released Calypso, the album that skyrocketed him to fame, in no small part due to its hit single, “Day-O (Banana Boat Song).”

The release introduced the wider American public to calypso music, and Belafonte was dubbed the “King of Calypso.” It was so successful, in fact, that it became the first LP to sell one million copies worldwide.

Harry Belafonte’s career had its highs and lows

As Harry Belafonte’s star continued to grow, he further expanded his resume. He starred in a number of films throughout the 1950s, many of which were controversial for the time period. Among them was 1957’s Inside the Sun, starring alongside Joan Fontaine. He was offered the role of Porgy in 1959’s Porgy and Bess, but disliked the racial stereotyping and denied the offer.

That same year, Belafonte starred in Revlon Revue: Tonight With Belafonte, for which he won an Emmy, making him the first Jamaican American and Black performer to win the award. He appeared in a number of television specials after this, alongside Julie Andrews, Lena Horne and Petula Clark, the latter of which saw him perform the anti-war song, “On the Path of Glory.” He also guest hosted a few episodes of The Tonight Show (1954-present) in 1968, filling in for Johnny Carson.

A highlight of Belafonte’s career was when Frank Sinatra recruited him to perform at President John F. Kennedy‘s inaugural gala, alongside the likes of Mahaila Jackson and Ella Fitzgerald.

His popularity began to see a slight decline in the 1970s, leading him to spend the majority of the decade on tour. He released his final calypso album in 1971 and didn’t follow it up with a release until ’88’s Paradise in Gazankulu. Belafonte starred alongside John Travolta in 1995’s White Man’s Burden, and eight years later performed his last concert. A decade after, in 2018, he appeared in his last theatrical role, Spike Lee’s BlacKkKlansman.

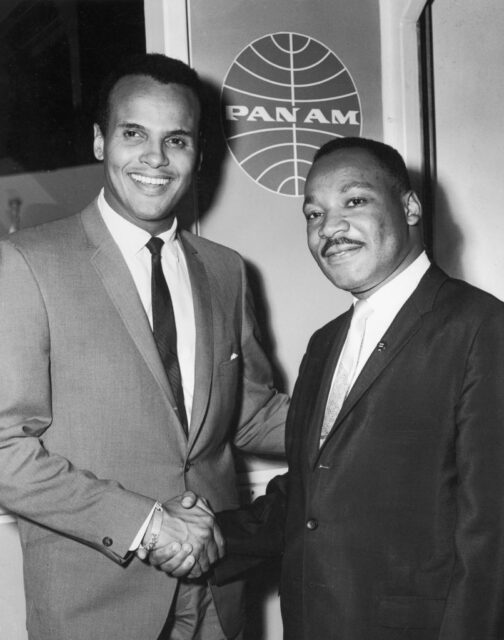

Close friends with Martin Luther King Jr.

Harry Belafonte was a close confidant of Martin Luther King Jr. The pair shared similar views when it came to the civil rights movement, with the former going so far as to not perform in the American South between 1954-61.

Belafonte met King in 1956 and immediately aligned himself with the civil rights leader. He helped support his family, and even went out of his way to bail King out of the Birmingham, Alabama jail during 1963’s Birmingham Campaign – he even raised $50,000 to secure the release of other leaders within the movement. On top of that, he also helped organize the 1963 March on Washington.

The pair’s connection led to Belafonte being blacklisted during the McCarthy Era.

Harry Belafonte’s activism spanned decades

Later in life, Harry Belafonte commented that “I wasn’t an artist who’d become an activist. I was an activist who’d become an artist.” He was largely inspired by Paul Robeson, who was not only against racial discrimination in America, but also Western colonialism in Africa – sentiments Belafonte echoed.

Outside of his campaigning for the civil rights movement, the singer also voiced his opinions on political issues and the rights of those across the world. Comments about the US invasion of Grenada and the arrests of the Rosenbergs were seen as controversial.

In 1985, Belafonte helped organize “We Are the World,” the Grammy-winning, multi-artist song that aimed to raise money for Africa. Two years later, he was named a UNICEF Goodwill Ambassador, a title he held until his death. His efforts were forever immortalized in the 2011 documentary Sing Your Song, and he received an Academy Award for his humanitarian work in ’14.

Loss of the ‘King of Calypso’

In the final decades of this life, Harry Belafonte suffered from a number of health issues. He was diagnosed with and beat prostate cancer in the 1990s, and, in 2004, suffered a stroke, which resulted in him losing his inner-ear balance.

More from us: Henry Fonda Served In the US Navy During WWII – He Didn’t Want to ‘Be a Fake In a War Studio’

During the last four years of his life, Belafonte reportedly began to lose his sight, leading him to largely withdraw from public life. On April 25, 2023, at the age of 96, he passed away at his home in Manhattan’s Upper West Side. His cause of death was deemed to be congestive heart failure.