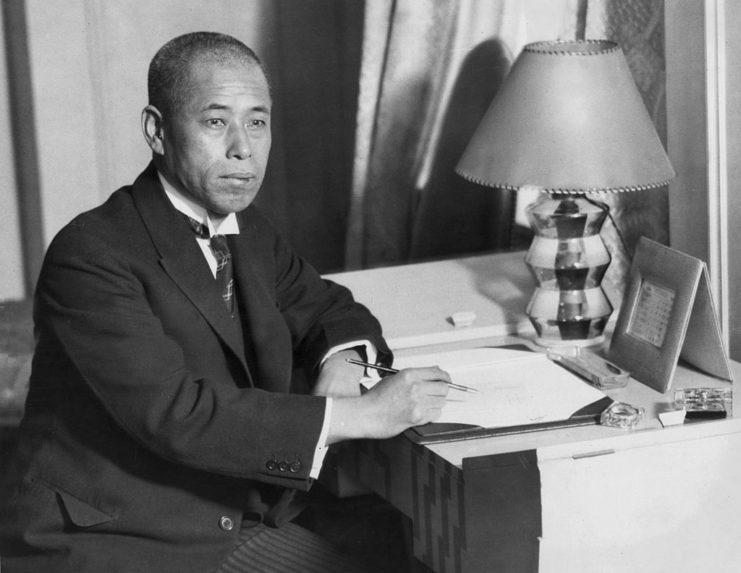

Isoroku Yamamoto, a senior admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy, was uniquely positioned to understand the United States—its culture, its people, and most importantly, its military and industrial power. His years spent in America, including time as a naval attaché in Washington, D.C., left him with a profound respect for the country’s capabilities and a deep awareness of the risks involved in confronting it militarily.

Yet, despite his personal reservations and appreciation for American strength, Yamamoto ultimately devised the plan for the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. Bound by loyalty to Japan’s high command and pressured by the nation’s strategic ambitions, he used his firsthand knowledge of the U.S. to carry out what he hoped would be a decisive blow. Though he understood the danger of awakening a formidable opponent, Yamamoto followed through with one of the most infamous surprise attacks in military history.

Isoroku Yamamoto’s upbringing and early career

He graduated from the Imperial Japanese Naval Academy in 1904 and saw combat in the Russo-Japanese War. At the pivotal Battle of Tsushima, Yamamoto sustained injuries that cost him the index and middle fingers on his left hand—a sacrifice that earned him recognition for bravery and accelerated his rise within the naval ranks.

By 1916, he had attained the rank of lieutenant commander, and just three years later, he was promoted to commander, solidifying his place among Japan’s rising military elite.

Experience in the US, rivalry with the Japanese Army

Yamamoto spent a fair amount of time in the US during the 1920s and ’30s. He was a student at Harvard University from 1919-21. He also had two postings as a naval attaché in America, where he learned to speak fluent English. Yamamoto created controversy in 1937 when he apologized to the US for Japan’s 1937 bombing of the gunboat USS Panay.

The Imperial Japanese Army was significantly more aggressive and pro-war than its Navy, and was angered by Yamamoto’s opposition to a pact with Germany and Italy. Following his apology to the US, he received death threats, to which he said:

“To die for Emperor and Nation is the highest hope of a military man. After a brave hard fight the blossoms are scattered on the fighting field. But if a person wants to take a life instead, still the fighting man will go to eternity for Emperor and country. One man’s life or death is a matter of no importance. All that matters is the Empire.”

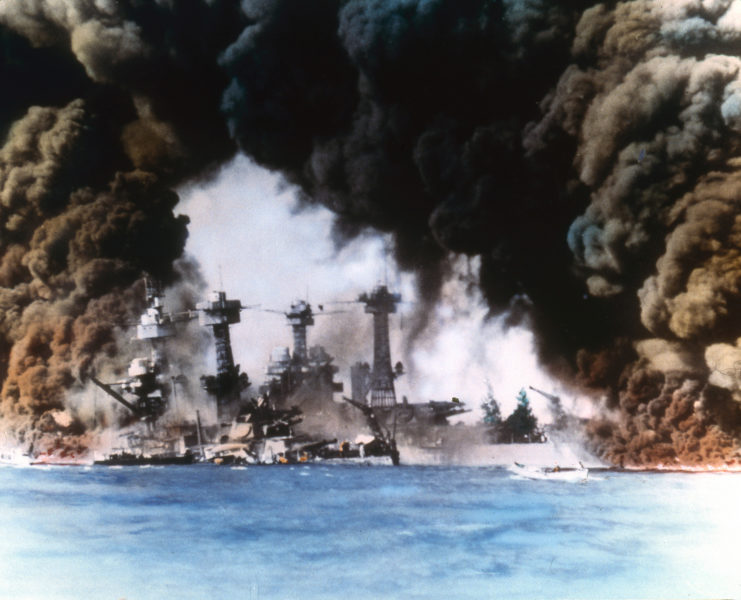

Attack on Pearl Harbor

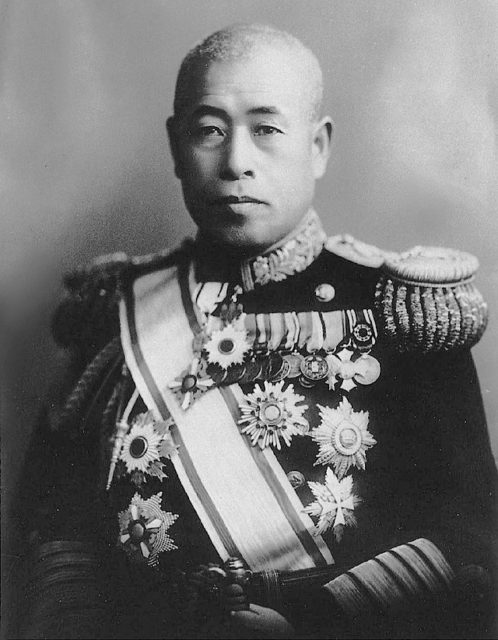

Isoroku Yamamoto’s rise through the ranks of the Imperial Japanese Navy was marked by his sharp intellect and disciplined approach to warfare, culminating in his promotion to admiral in November 1940. Though his forward-thinking strategies often put him at odds with Japan’s Army leadership, Yamamoto was well-regarded within naval circles and benefited from the influential support of the Imperial family.

Privately, Yamamoto harbored serious doubts about engaging in war with the United States. He understood that Japan’s industrial limitations made a long-term conflict unwinnable. His plan for the attack on Pearl Harbor reflected this grim calculus: deliver a swift, overwhelming strike that would cripple U.S. naval power, shock the American public, and create a window for Japan to secure dominance in the Pacific.

In purely tactical terms, the attack achieved its goals, destroying four battleships and nearly 200 planes in one devastating morning. But the strategic fallout was exactly what Yamamoto feared. Rather than forcing America to the negotiating table, it ignited a unified and unrelenting war effort. The very resolve and industrial might Yamamoto had respected now turned fully against Japan—a response he had predicted, but could not prevent.

Battle of Midway and Yamamoto’s death

Despite initial Japanese successes after Pearl Harbor, Yamamoto advocated for continued attacks on the US Fleet. The Battle of Midway in June 1942 was intended to maintain Japanese offensive momentum. However, prior to the operation, US forces were able to break the Japanese Naval Code. This intelligence allowed Admiral Chester Nimitz to prepare effectively, resulting in a decisive US victory that shifted the course of the war.

Following setbacks and defeats at Guadalcanal and Midway, Yamamoto embarked on a morale-building tour for his forces. US intelligence intercepted and decrypted details of his itinerary, enabling American pilots to shoot down his plane on April 18, 1943. Posthumously, Yamamoto was honored with the title of Marshal Admiral and awarded the Order of the Chrysanthemum by Japan. Additionally, he received Germany’s Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross.

Yamamoto’s legacy

Yamamoto has been featured in a number of films about Pearl Harbor and World War II. Moviegoers may remember him for the Tora! Tora! Tora! (1970) line that he may or may not have uttered: “I fear that all we have done is to awaken a sleeping giant and fill him with a terrible resolve.” The line was also referenced in 2001’s Pearl Harbor.

Historians, however, are not sure he ever actually made this observation.

Yamamoto was also portrayed by legendary actor, Toshiro Mifune, in three separate films: Rengo Kantai Ichokan Yamamoto Isoroku (1968), Gekido no showashi ‘Gunbatsu’ (1970) and Midway (1976).