Escort carriers played a unique role during World War II, particularly in the Pacific Theater, where they faced attacks from above, below and from other vessels. They were sometimes used to defend troops tasked with launching attacks, and commonly served as defensive barriers for ships carrying important cargo. One of these carriers was the USS Johnston (DD-557), which was under the command of Ernest Evans during the Battle off Samar in October 1944.

Ernest Evan’s service in the US Navy prior to World War II

Ernest Evans was born on August 13, 1908 in Pawnee, Oklahoma. After graduating high school, he attempted to enlist in the US Marine Corps, but was denied because of a knee injury. The following year, after winning a fleet competition, he was allowed to join the US Navy, attending the US Naval Academy.

Following his graduation in 1931, he was assigned to Naval Air Station San Diego (today known as Naval Air Station North Island). He remained there until August 7, 1933, after which he served on a number of vessels. In order, Evans served aboard the USS Colorado (BB-45), Roper (DD-147), Rathburne (DD-113) and Pensacola (CA-24).

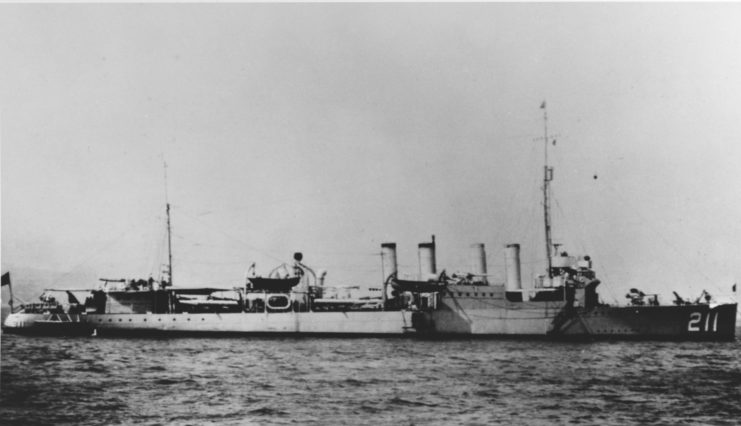

On the latter, he served as an aviation gunnery observer, after which he was assigned to sea duty aboard the USS Chaumont (AP-5), Cahokia (ATA-186), Black Hawk (AD-9) and Alden (DD-211).

The United States enters the Second World War

Ernest Evans remained onboard the USS Alden after the United States entered the Second World War. He became the ship’s commanding officer on March 14, 1942, serving in this capacity until July 7, 1943. Details of his wartime service during this period are vague. However, it’s known he served in operations in New Guinea, the Dutch East Indies, Australia and the Caribbean, where Alden was primarily used to escort troop and supply convoys.

When Evans’ time onboard Alden came to an end, he was ordered to serve aboard the USS Johnston. He assumed command of the destroyer on October 27, 1943, following her commission. During the ceremony, Evans declared to his crew and onlookers, “This is going to be a fighting ship. I intend to go in harm’s way, and anyone who doesn’t want to go along had better get off right now.”

Little did he know how accurate this statement would prove to be.

USS Johnston (DD-557)

The USS Johnston was a roughly 2,100-long ton Fletcher-class destroyer and served as an improved version of the destroyers that took part in the early years of the Second World War. She operated at a maximum speed of 38 knots, and had ample armaments to defend against submarines, aircraft and other ships, including anti-aircraft guns, torpedo tubes, depth charge throwers and racks, and dual-purpose naval guns.

Ernest Evans and Johnston were assigned to the US Pacific Fleet, primarily sailing the Marshall Islands and the Leyte Gulf. Her service during the conflict included attacking the beaches of Kwajalein and Eniwetok atolls during the Gilbert and Marshall Islands Campaign, shelling the military fortifications on Kapingamarangi Atoll and patroling the waters around the Solomon Islands. She was also part of the convoy that participated in the Battle of Guam.

In September 1944, Johnston acted as a defender for the escort carriers providing air support during the Battle of Peleliu, before sailing to the Leyte Gulf to serve in a similar capacity.

Ernest Evans’ bravery during the Battle off Samar

In October 1944, Ernest Evans and his crew joined the US 7th Fleet’s Escort Task Unit (TU) 77.4.3 – better known as “Taffy 3.” They were tasked with defending the Leyte beachhead and the area north of Leyte Gulf, as Gen. Douglas MacArthur had traveled back to the Philippines.

On October 25, a pilot gave word of a large Japanese contingent – which included the battleship Yamato – traveling through the San Bernardino Strait, directly to the area where Taffy 3 was located. Unfortunately, the American forces were significantly outnumbered, as most of the vessels in the US 7th Fleet had left two days earlier to defend against an alleged enemy force in a different location.

Some sources claim Evans told his crew, “A large Japanese fleet has been contacted. They are fifteen miles away and headed in our direction. They are believed to have four battleships, eight cruisers, and a number of destroyers. This will be a fight against overwhelming odds from which survival cannot be expected. We will do what damage we can.”

Evans led the American attack with the USS Johnston. He ordered his crew to create a smokescreen to hide the escort carriers from enemy gunfire, after which he led Johnston into a solo torpedo attack on the Japanese fleet. Evans and his crew knocked out a Japanese cruiser and damaged some of the other ships, but in doing so sustained extensive damage to Johnston, which had taken direct hits from powerful 14-inch guns.

They held out against the attack for approximately three hours, after which they lost power and were completely surrounded. By then, a severely injured Evans ordered his men to abandon ship, doing so shortly before Johnston went under. Of the 327 crew onboard, 186 died. Along with Johnston, three other American vessels sank during the battle: the USS Hoel (DD-533), Gambier Bay (CVE-73) and Samuel B. Roberts (DE-413).

Ernest Evan’s legacy

In what became known as the Battle off Samar, the Americans achieved an incredible and unexpected victory, stopping the Japanese fleet from breaking through and attacking the Leyte Gulf. For her incredible defense, the USS Johnston was awarded the Presidential Unit Citation, as well as six battle stars for her overall war service. The destroyer’s wreck wasn’t discovered until October 2019, lying over 21,000 feet below the ocean’s surface – the second deepest shipwreck ever surveyed.

It’s believed Ernest Evans survived Johnston‘s sinking; he was seen in the water, but never heard from again, and his body was never found. He was posthumously given the Medal of Honor, and was also awarded the Bronze Star with Combat “V,” Purple Heart, China Service Medal, American Defense Service Medal, Fleet Clasp, Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with six engagement stars, the World War II Victory Medal, and the Philippine Defense and Liberation Ribbons with one star.

More from us: Manila American Cemetery Is Home to More US WWII Dead Than Any Other Site

In 1955, the USS Evans (DE-1023) was named in his honor, although the vessel was decommissioned in 1968. Of Evans’ command of Johnston, Ensign Robert C. Hagen said, “The Johnston was a fighting ship, but he was the heart and soul of her.”