During WWII, thousands of Allied soldiers, sailors, and airmen were captured by the Axis powers. However, it did not mean they were cut off from the war effort. British military intelligence went to great lengths to open secret lines of communication with those men and used them in their fight against the enemy.

Why the Messages Mattered

Before getting into how the intelligence services communicated with prisoners, it is worth considering why such communication was so important. There were two main reasons – one based on the information going into the camps; the other on the information coming out.

The flow of information into the prison camps supported the efforts of the PoWs to resist and escape their captors. As the film The Great Escape so dramatically showed, many PoWs considered it their duty to cause trouble for the enemy. If they escaped to Allied territory, they could once again join the war. Even if they broke out and were recaptured, they would tie down Axis resources in chasing them; resources that might otherwise have been used in the fighting.

By opening up communication channels, British intelligence provided advice and information to support escapes. They even sent materials to help.

The information coming out of the camps, though less dramatic in the stories it inspired, was equally valuable to the war effort. By definition, PoWs were men who had seen action. They might, therefore, have valuable information about enemy equipment, tactics, and positions. Those who had escaped and were recaptured might know about what was happening in the local area. Gossip overheard in the camp could be valuable. All of it was fed back to British intelligence.

One particularly important example happened in 1942. A British radar expert, captured by the Germans, sent coded information to Britain about the radar equipment of German night-fighters. It helped to inform the work done by R. V. Jones, MI6’s scientific expert.

The Dotty Codes

How were these valuable lines of communication set up?

It began with what the intelligence analysts referred to as “dotty codes.” They were set up in advance between soldiers and their wives to enable them, if captured, to liaise without their guards understanding. The personal codes often used dots to show where the start and end of a coded message were – hence the “dotty” name.

The system had initially been set up for personal communication. It allowed prisoners to send private messages to their loved ones knowing they would not be censored. When the intelligence services found out about the system, they started using it to exchange less personal info.

Moving On From Dotty

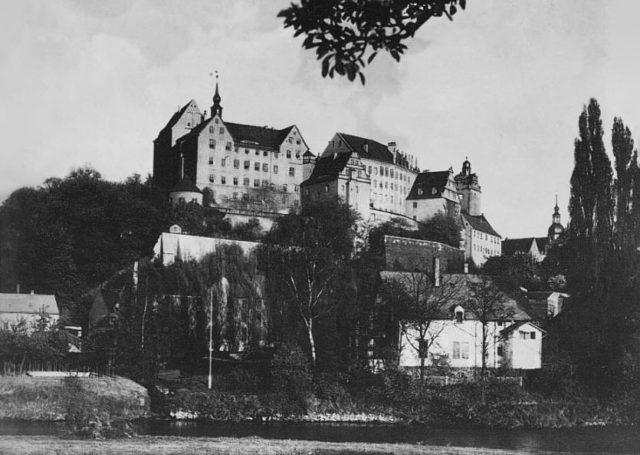

MI9, the department responsible for communication with PoWs, used the dotty codes as a starting point for a more developed system of covert communication. Using dotty codes, they provided prisoners with the information needed to start using other, more sophisticated forms of cryptography. For example, a set of codes was sent on handkerchiefs to Captain Rupert Barry, who spent four years as the coding officer for the PoWs inside Colditz Castle, the prison for persistent escapees. A message encoded in a letter from Barry’s wife told him to wash the handkerchiefs, revealing the code hidden on them.

MI9 developed a range of codes for communicating with prisoners. They wrote letters, apparently dealing with mundane or personal issues, to hide messages in them. As they did not have a lot of staff, they brought in people to write the letters. That way, they removed the risk of prison censors recognizing the same handwriting on letters to several different prisoners and become suspicious.

As with so much covert work, the devil was in the details.

HK

Developed in 1940, HK was an example of the sort of simple code that could be so effective in communicating with prisoners. MI9 devised it in collaboration with the Foreign Office, who supplied an expert to assist in its implementation.

In the HK system, the way the date on a letter was written sent a message to the prisoner. It told him where in the letter the hidden message was. The opening words were then used to covertly inform which part of the HK code was being used. With that information, the prisoner could decode the message, but it was impenetrable to the guards.

The BBC

Despite the best efforts of the guards, most groups of PoWs had access to a radio. They were either smuggled in or assembled in the camp using the skill of the captives. They could be used to receive news and entertainment from home.

Knowing that prisoners were listening in, MI9 started hiding messages in programs broadcast on the BBC. An especially popular choice was Radio Padre’s Forces program on Wednesday nights. The Very Reverend Dr. R. Selby began his broadcast in different ways. If the first words from him were “Good Evening, Forces,” then the prisoners knew there would be a coded message. They used shorthand to take down the content of the transmission, then decrypted it afterward.

Special Parcels

The ultimate in covert communication was smuggling materials into the camps. In May 1943, 47 of the 413 messages received by MI9 were acknowledgments that such parcels had got through.

To ensure packages containing covert materials were not searched, messages were sent telling prisoners which ones were important. They looked out for the marked parcels and got them out of mailrooms through slight of hand or bribes to guards. Such packages could provide coding materials, escape tools, or radio equipment, essential to the prisoners’ ability to communicate.

By the beginning of 1942, communications had been set up with every officer POW camp in Germany. Hundreds of messages were sent back and forth without the enemy knowing. PoWs continued to contribute to the war.

Source:

Ian Dear (1997), Escape and Evasion: PoW Breakouts In World War Two;