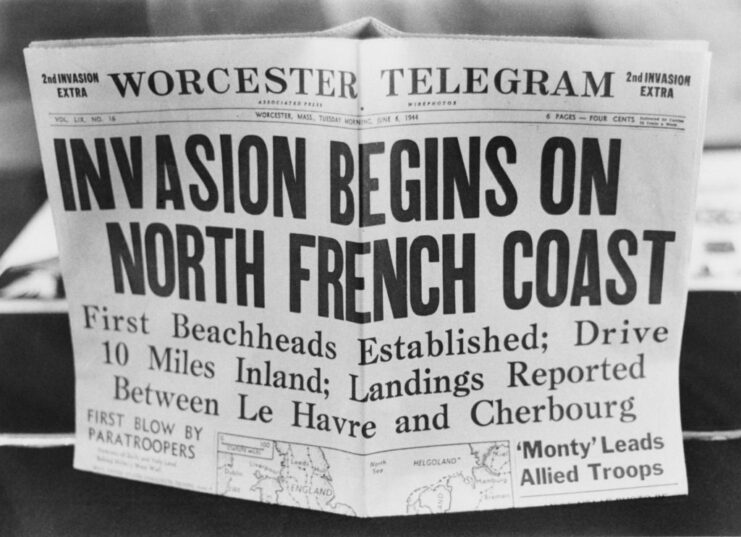

D-Day, which took place on June 6, 1944, remains one of the most pivotal moments of World War II. On that day, Allied forces—comprising U.S., British, and Canadian troops—launched a massive invasion across the English Channel. The goal was to break through the heavily fortified German defenses along the Normandy coast in France and begin the liberation of Western Europe.

The operation was immense, involving over 156,000 soldiers, supported by thousands of ships and planes. The meticulous planning that went into D-Day took months, with every detail accounted for. This operation was not only a major military campaign but also the beginning of the end for Germany’s control over Europe.

Here are some essential facts about the D-Day landings, highlighting their ongoing significance in history.

Nearly 160,000 Allied troops were involved in the D-Day landings

The D-Day landings, which significantly influenced the outcome of the Second World War, involved a massive force of well over 100,000 Allied troops. Of the approximately 160,000 soldiers who participated, 83,000 were British and Canadian, while 73,000 were American. In contrast, the German forces consisted of about 50,000 troops.

As Operation Overlord, or the Battle of Normandy, progressed, more than two million Allied soldiers contributed to the liberation of France.

Operation Bodyguard came before Operation Overlord

Before the D-Day landings, the Allies developed many strategies to ensure their success, including tricking the Germans through Operation Bodyguard. This plan was meant to fool German forces into thinking the main Allied attack would happen at Pas-de-Calais instead of northwestern France. As a result, the Germans moved troops and supplies away from the real D-Day landing sites.

One key part of Operation Bodyguard was Operation Copperhead, This involved hiring a lookalike to pose as Bernard Montgomery, a top British officer, in different Allied territories. The idea was to make the Germans question whether Montgomery was involved in D-Day planning since his supposed travels would suggest he wasn’t overseeing the operation. The impersonator also helped spread false information to support the larger deception strategy.

D-Day was initially slated to occur on June 5, 1944

While June 6, 1944, is etched in history, D-Day wasn’t initially planned for that date. The landings were originally scheduled for June 5, but were delayed by 24 hours after Irish postmistress Maureen Flavin Sweeney reported an approaching storm.

Supreme Allied Commander Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower made the critical decision to postpone the operation. This choice not only contributed to the mission’s success, but also saved countless Allied lives.

Thousands of ships and landing craft were involved in D-Day

D-Day was centered around amphibious landings, which means the troops needed vessels to get across the English Channel.

It’s reported that nearly 7,000 ships and landing craft were used to ensure the success of the landings. Of that total, 80 percent were supplied by the British and 16.5 percent came from the United States.

What does the ‘D’ in D-Day stand for?

For nearly 80 years since the Normandy landings, people have wondered: what does the “D” in D-Day actually mean? Surprisingly, the answer isn’t very exciting.

The “D” simply stands for “Day,” so “D-Day” literally means “Day-Day“. Not exactly the most natural-sounding name, right?

A fatal live-fire rehearsal

A lot of preparation went into the D-Day landings, much of which involved training troops for what they could expect upon arriving in German-occupied France. Several coastal villages were taken over and numerous rehearsals were held.

One practice run was the fatal Exercise Tiger, which resulted in the deaths of over 700 Allied troops. Many of the casualties were killed during a live-fire exercise, while many others perished during what became known as the Battle of the Lyme, during which E-boats operated by the Kriegsmarine attacked Tank Landing Ships (LST) in the English Channel.

What obstacles did the Allies face on the landing beaches?

Knowing the Allies were likely to attack France, the Germans fortified the coast with obstacles designed to slow down or kill invading troops.

One of the most famous defenses was the Czech Hedgehog—X- or L-shaped barriers made of metal or wood that could stop tanks from moving forward. In addition to these, the Germans placed tall wooden posts called Holzpfähle, standing 13 to 16 feet high, scattered across beaches and fields. Hidden throughout Normandy were teller mines—flat, disc-shaped explosives filled with 5.5 kilograms of TNT, set to explode under the weight of a soldier or vehicle.

No one wanted to wake the Führer…

As mentioned earlier, the Germans knew an Allied invasion was coming, but that didn’t mean they were ready to do everything possible to stop it. What’s one big example? Waking the Führer from his slumber.

Operation Overlord began in the early morning hours of June 6, 1944. When word of the landings reached the Führer’s headquarters—the Wolf’s Lair—at 4:00 AM, he was still asleep. Out of fear of his temper, no one woke him up. Without his approval, German forces didn’t take action, allowing Allied troops to move inland without immediate resistance.

By the time the Führer finally gave the order, it was already several hours too late.

Sixteen soldiers received the Medal of Honor

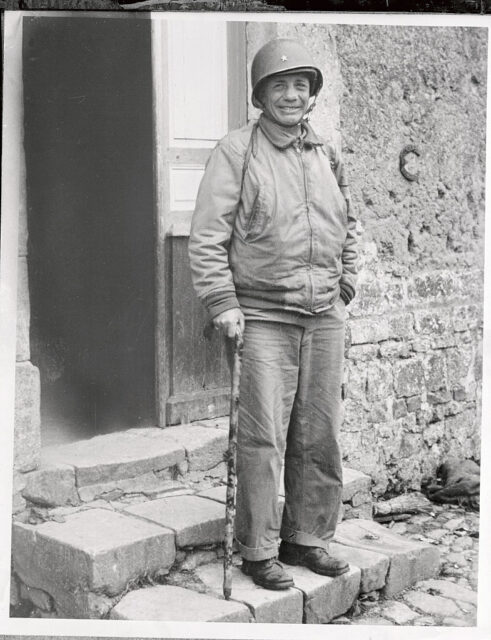

During the D-Day landings and the subsequent Battle of Normandy, 16 American soldiers were awarded the Medal of Honor for their extraordinary bravery, with nine of them receiving the medal posthumously. Among these, four medals were awarded for actions on June 6, 1944: Pvt. Carlton W. Barrett, First Lt. Jimmie W. Monteith, Jr., T/5 John J. Pinder, Jr., and Brig. Gen. Theodore Roosevelt, Jr.

The name Roosevelt may be particularly familiar, as Theodore Roosevelt, Jr. was the eldest son of U.S. Theodore Roosevelt. On D-Day, Roosevelt served a crucial role in leading the forces that landed on Utah Beach, ensuring the success of the beachhead and contributing significantly to the Allied victory.

Lt. Herbert Denham ‘Den’ Brotheridge

Have you ever wondered who the first Allied casualty of the D-Day landings was? According to reports, it was Lt. Herbert Denham “Den” Brotheridge, an officer in the British Army.

Serving with the 2nd Battalion, Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, he was killed while taking part in Operation Tonga, a mission undertaken by the British 6th Airborne Division to take control of and destroy the Merville Gun Battery. The site was approximately eight miles from Sword Beach.

While taking on German machine gunners, Brotheridge was hit in the back of the neck by enemy fire. While attempts were made to render medical aid, he perished.

Playing the bagpipes

Several notable individuals participated in the D-Day landings, but none were as unique as “Piper Bill” Millin, whose music led British Commandos from Sword Beach to Pegasus Bridge.

Millin played the bagpipes under Simon Fraser, 15th Lord Lovat, who’d been appointed the commander of the 1st Special Service Brigade (1st SSB). Under a hail of enemy and friendly fire, the former played his music, walking the entire length of Sword Beach three times, before moving toward the key bridge area.

How did he survive without a weapon, you ask? Well, according to a German soldier who spoke to Millin decades later, the enemy forces thought he was “off your head” – they didn’t want to waste their bullets on him!

Outnumbering the Luftwaffe 30:1

Approximately 11,000 Allied aircraft participated in the D-Day landings, a sizeable number, given the dwindling numbers of the Luftwaffe.

According to the BBC, the Allies outnumbered the Germans 30-to-one in the air. Given this, the latter failed to down any of the former’s aircraft in air-to-air combat.

How many casualties were suffered?

On June 6, 1944, alone, several thousand casualties were suffered by both sides. The Allies inflicted between 4,000 and 9,000 on the Germans, while they themselves experienced just over 12,000. According to the National WWII Museum, the breakdown for the Allies was:

- United States – 8,230

- United Kingdom – 2,700

- Canada – 1,074

Much of the footage was lost in the English Channel

Have you ever wondered why so little in the way of video footage exists of the D-Day landings? Well, the reason is it was accidentally dumped in the English Channel – true story.

American film director John Ford was tasked with capturing footage of the landings on Omaha Beach, with the assistance of the US Coast Guard. The majority of the film reels were subsequently placed in a duffel bag bound for Britain. However, on the way, the bag was accidentally dropped into the English Channel by Maj. W.A. Ullman, a junior officer.