When it comes to American military history, few units are as storied and famous as the Harlem Hellfighters. Officially the 369th Infantry Regiment, this all-Black unit from New York fought with extraordinary bravery during the First World War, earning the respect of those on the battlefield, despite continuing to fight racism at home.

Despite facing segregation and discrimination, the Hellfighters distinguished themselves in Europe, spending more time in combat than any other American unit.

Formation of the Harlem Hellfighters

The 369th Infantry Regiment began as the 15th New York National Guard Regiment of the New York Army National Guard. It was officially organized in June 1916 in New York City and composed of African-American enlisted men, with Black and White officers.

New York Gov. Charles S. Whitman appointed Col. William Hayward to command the unit, who set high standards for integrated leadership and respect. Recruitment efforts focused on Harlem’s African-American community (at the time, around 50,000 of Manhattan’s 60,000 Black residents lived in Harlem), but volunteers also came from upstate New York, New Jersey, Connecticut and Pennsylvania.

By mid-1917 the regiment mustered roughly 2,000 men, ranging from teenagers to middle-aged working-class volunteers, all motivated to serve and prove their loyalty in World War I.

Training in the United States

On 25 July 1917, the 15th New York National Guard Regiment was called into federal service for World War I. The men trained in basic soldiering at Camp Whitman, New York, and performed security duties guarding raillines and construction sites around the state.

In October 1917, the regiment was moved to Camp Wadsworth, South Carolina, for advanced training. There, they encountered open racism under Jim Crow conditions; local businesses and even some White soldiers harassed the Black troops.

In one incident, Lt. James Reese Europe, the regiment’s Black bandleader, and Pvt. Noble Sissle were refused service at a hotel newsstand and assaulted by a White proprietor. Scores of soldiers from the 15th and sympathetic White New York National Guardsmen from a neighboring unit converged, prepared to retaliate, but Europe intervened to defuse the situation until military police arrived.

Such hostility prompted William Hayward to urge the War Department to get his unit out of the South before violence erupted. The 15th left Spartanburg, and, by late December, were bound for Europe.

Assigned to the French Army

The 15th New York National Guard Regiment sailed from New York and arrived in France shortly after Christmas. Upon their arrival in France, the 15th was initially relegated to labor duties behind the lines, despite their infantry training. Throughout January 1918, the men toiled at Saint-Nazaire and other depots, unloading ships, laying railroad tracks and digging trenches – a common fate, as nearly 90 percent of African Americans in the US Army were assigned to service roles, rather than combat.

Frustrated at being kept from the front, William Hayward petitioned the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) command for a combat assignment. Meanwhile, the Allied high command faced a manpower crisis after the bloody campaigns of 1917 and urgently requested American reinforcements. Gen. John J. Pershing, reluctant to break up White American units, agreed to the transfer of the 15th to French command to bolster the exhausted French ranks.

Redesignated the 369th Infantry Regiment

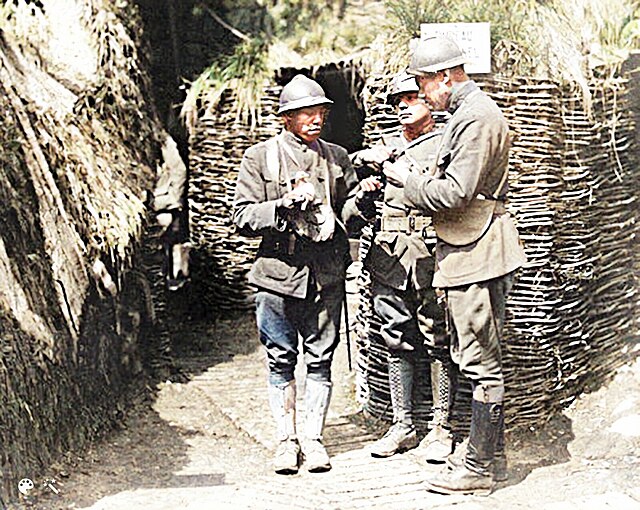

On March 1, 1918, the regiment received a new federal designation – the 369th Infantry Regiment – as part of the provisional 93rd Division. A few weeks later, the entire 369th was formally reassigned to the French Armed Force’s 4th Army, joining the 16th Division under Gen. Henri Gouraud. The men turned in their American rifles and were issued 8-mm rifles, Chauchat automatic rifles, bayonets, gas masks, helmets and other kit to integrate seamlessly with French forces.

However, they continued to wear US uniforms, but now with French horizon-blue helmets and equipment.

The US Army’s segregationist policies went so far as to distribute a secret memorandum, drafted by an American staff officer, Col. J.L.A. Linard, warning French commanders not to treat Black American soldiers as social equals, using racist lies to discredit the troops. The French largely ignored this. Having employed colonial African units for decades, they were accustomed to soldiers of color and generally treated the 369th as they did any other combat unit.

Entering combat on the Western Front

In May 1918, the 369th Infantry Regiment (nicknamed the “Harlem Rattlers”) entered frontline trenches under French control, seeing their first combat in the spring of 1918. On May 8, the regiment went into the line in the Champagne sector. From that point on, they’d serve an astonishing 191 continuous days in thee trenches, longer than any other American regiment in the First World War.

The regiment’s baptism of fire came in the quiet Argonne Forest and Champagne region, conducting patrols and raiding parties against German positions. In the predawn hours of May 15, 1918, Pvt. Henry Johnson and Pvt. Needham Roberts were on sentry duty at an isolated observation post on the edge of the Argonne Forest when a German raiding party attacked their position.

Johnson and Roberts fought back ferociously in close-quarters combat. When Roberts was badly wounded by a grenade, Johnson ordered him to lie low, then singlehandedly engaged the Germans with his rifle, grenades and a bolo knife once he was fully out of ammunition. Johnson killed at least four of the enemy and wounded dozens of others, sustaining 21 wounds himself.

The pair’s stand thwarted the German raid and prevented Roberts from being taken prisoner. News of this spread, and both men received France’s Croix de Guerre for gallantry, making them the first American soldiers in World War I to earn the honor.

The 369th’s early combat actions, including aggressive patrols, earned respect from French high command and infuriated the Germans, who reportedly began calling these relentless fighters Hellfighters, hence the moniker, “Harlem Hellfighters.”

Throughout June 1918, the 369th remained in brutal trench warfare in Champagne. They endured daily artillery bombardments, gas attacks and small-scale skirmishes while holding their sector. The regiment was under constant fire, with no relief rotation for more than two months. By early July, the entire unit was exhausted, but hardened. On July 3, they finally pulled back to the rear for a brief rest and to integrate a draft of replacement troops.

Harlem Hellfighters and the Champagne-Marne Defensive

The respite was short. On July 15, 1918, Germany launched its final major offensive on the Western Front: the Second Battle of the Marne. The Harlem Hellfighters, now attached to the French 161st Division, were thrown back into action.

They occupied positions along the Marne and in the Champagne region as the German forces struck hard. The 369th endured “murderous shelling” from enemy artillery during the defensive fighting, but stood firm and held the line against the onslaught; not a single Hellfighter position yielded.

Once the German offensive was blunted by late July, the Allies swiftly went on the counteroffensive. The 369th marched south and west with the 161st, pressing the retreating Germans. In mid-to-late August, they saw continuous combat as the French and American militaries advanced.

By August 19, after over three months on the front without relief, the 369th was finally withdrawn for rest and to absorb more replacements. Enemy propaganda leaflets were dropped over their lines, urging the African-American soldiers to abandon a nation that oppressed them, but the Hellfighters ignored these attempts at subversion. Their discipline and morale remained intact, despite the constant hardship.

Major casualties suffered in the fight for Séchault

Freshly refitted, the 369th Infantry Regiment returned to the fight for the final Allied push of the Great War. On September 25, 1918, the French 4th Army launched a major offensive in concert with the American drive in the Meuse-Argonne sector. The Harlem Hellfighters advanced resolutely against well-entrenched German positions in the Champagne-Argonne region. In late September, they fought their most famous and costly battle.

On September 29, the 369th Infantry assaulted and captured the strategic village of Séchault, in the Ardennes, spearheading the French 161st Division’s attack. The unit pushed nearly 14 km into enemy territory, at one point advancing faster and farther than the French units on its flanks.

However, this achievement came at a devastating price. The fight for Séchault and the surrounding hills inflicted some of the heaviest casualties suffered by any American regiment in World War I. In just a few days of combat, the 369th had incurred approximately 850 casualties among its men. Entire platoons and companies were cut down by machine gun fire and shelling.

One company that took Séchault in a bayonet charge entered the battle with 250 men and mustered barely five dozen able-bodied survivors afterward. By the end of September, the regiment had lost about 144 killed and nearly 1,000 wounded in the Meuse-Argonne offensive. These losses, roughly half the regiment’s combat strength, made the Hellfighters one of the most bloodied US units of the entire war.

End of World War I

Badly mauled and exhausted, the 369th Infantry Regiment was pulled out of the line in early October 1918, as the French 161st Division was relieved. Their courage at Séchault didn’t go unrecognized: for its role in the offensive, the entire regiment earned a French unit citation. Gen. Georges Lebouc pinned the coveted Croix de Guerre ribbon to the 369th’s regimental colors.

After a short rest, the Hellfighters returned to duty in late October, this time in a relatively quiet sector. They were shipped to the Vosges Mountains in eastern France, where the action was less intense. They manned forward positions through the final days of the war.

When the Armistice took effect on November 11, 1918, the 369th were still standing guard on the Vosges frontline, triumphant but battered. Not content to rest after a grueling war, just six days after the Armistice, the regiment joined the march into Germany as part of the Allied occupation force.

On November 26, 1918, they reached the banks of the Rhine, with William Hayward leading the column. The 369th was the first Allied unit to pierce into Germany after the ceasefire. For a brief time, these Black American soldiers proudly stood on German soil as victors, a fact laden with irony given that many back home still denied them basic rights.

What honors did the Harlem Hellfighters receive?

In total, the 369th Infantry Division sustained approximately 1,500 casualties (killed, wounded or missing) by the end of the First World War I – the highest casualty count of any US regiment in the conflict. Despite this, they achieved an undefeated record on the battlefield: they never lost a trench, never yielded an inch of ground and never had a man taken prisoner by the enemy. Every objective assigned to them was held or taken.

The 369th earned widespread recognition for its heroism. This included 171 Croix de Guerre medals awarded to individual troops for acts of gallantry in battle. Dozens of other Hellfighters received the US Distinguished Service Cross or other decorations from the American command for their bravery.

In addition, the entire 369th Regiment was decorated with a unit Croix de Guerre by the French government for its outstanding performance in the Champagne and Meuse-Argonne campaigns.

Return to the United States

After the Armistice, the 369th Infantry Regiment prepared to return home. In mid-December 1918, they traveled to a French port to embark for New York. An incident there underscored the continued bigotry they faced: the men were scheduled to leave aboard the US Navy transport USS Virginia (BB-13), but the ship’s White captain refused to let the African-American troops aboard.

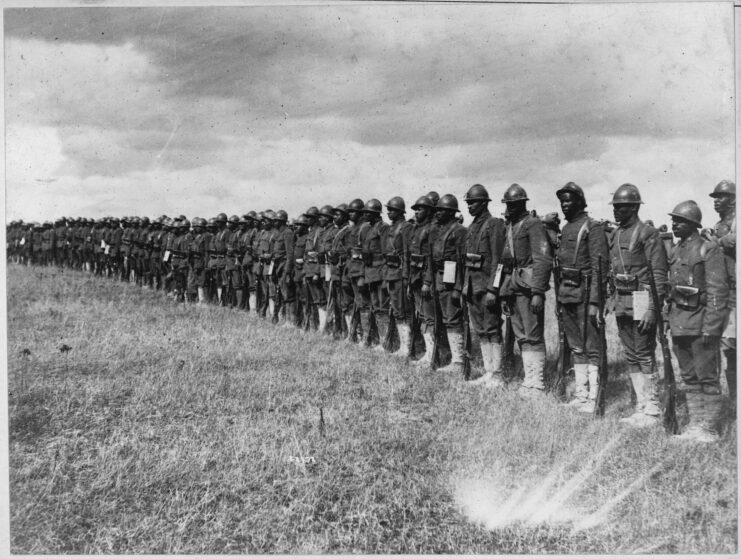

The Hellfighters were forced to await alternate transport. Eventually, they departed Europe and arrived back in New York in early 1919. On February 17, 1919, the 369th was welcomed home with a massive victory parade in Manhattan. That morning, thousands of spectators of all races lined Fifth Avenue, from Midtown to Harlem, waving flags and cheering in celebration.

Led by their famed regimental band playing joyous marches, the Harlem Hellfighters proudly marched 16 abreast in French-style formation, with war-weary faces set like stone. New York’s mayor and dignitaries reviewed the parade, and newspapers hailed the Black soldiers as heroes who’d fought with unrivaled courage. The event ended at the Armory, the regiment’s home station, where the men formally passed in review and were dismissed.

More from us: Tuskegee Airmen: The African-American Pilots Who Broke Barriers in World War II

Two weeks later, the 369th was officially demobilized at Camp Upton, New York. The Harlem Hellfighters had returned to American soil with their heads high.