Despite the large array of medals and decorations created to honor those who perform incredible acts of bravery, many are never recognized for their actions. This is often due to prejudice, political opinions and nationality getting in the way. One such case of this is the service of William Henry Johnson, a soldier with the first African-American unit in the US Army to see action during World War I.

More commonly known as Henry Johnson, the serviceman would go above and beyond the call of duty, fighting in hand-to-hand combat against overwhelming odds, while saving a fellow soldier in the process.

Henry Johnson enlisted in the New York National Guard

Henry Johnson’s early life is clouded in mystery, even to him. He claims to have been born July 15, 1892, in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, but whether this is true or not is unknown, as he also used different dates on various documents. In his early teens, he worked as a railway porter, carrying goods and luggage.

Johnson enlisted into the US Army in mid-1917, after learning that the New York National Guard’s 15th Infantry Regiment was recruiting. This regiment was known for only recruiting Black soldiers. He and his fellow infantrymen were deployed to France, arriving in January 1918.

Assigned to the French Army’s 161st Division

From the get-go, the eager regiment – at that point renamed the 369th Infantry Regiment and later becoming known as the “Harlem Hellfighters” – was relegated to menial tasks, such cleaning and moving goods. They were temporarily assigned to the 161st Division of the French Army by Gen. John J. Pershing. It’s believed the reason was that Pershing wanted to give African-American soldiers a chance to advance in leadership, which they couldn’t do in the segregated US Army.

The French Army had no such issue and gladly accepted the men as reinforcements, kitting them out with equipment. Johnson and his regiment were deployed to Outpost 20, near the Argonne Forest.

A nighttime raid was Henry Johnson’s chance to be a hero

On the night of May 14, 1918, Henry Johnson was unaware that he was about to experience the fight of his life. He, along with fellow soldier Needham Roberts, were on sentry duty on the edge of the forest. Their sentry shift was due to finish at midnight.

Two soldiers approached the pair to relieve them of their watch. Johnson, quickly recognizing the young men’s inexperience, opted to stay with them, rather than leave. Roberts returned to his trench to sleep, but Johnson soon heard movement, rustling and the clipping of wire cutters.

Suddenly, out of the darkness, a swarm of German troops attacked his position. Calling for help, Roberts ran to Johnson’s aid, but was struck by shrapnel and put out of action. He wasn’t completely out of the fight, however, as he passed hand grenades to his fellow American, who threw them at the advancing Germans.

Once the grenades ran out, Johnson opened fire with his rifle, being hit himself in the side, head and hand in the process. His weapon eventually jammed, becoming a hand-to-hand implement instead, being swung like a bat into the enemy.

Fighting for his life, Johnson was caught on the head with a devastating blow. Falling to the ground, dazed and beside his now-shattered rifle, he got back up and unsheathed his 14-inch bolo knife. He thrust, hacked and chopped with the blade, killing one man with a single strike. Noticing the Germans attempting to drag away the injured Roberts, he leaped upon them, stabbing one in the ribs, before fending them off.

Overall, the gruesome exchange lasted for around an hour. When reinforcements finally arrived, the Germans fled. Johnson’s incredible effort had saved the lives of both himself and Roberts, who received medical attention for their wounds.

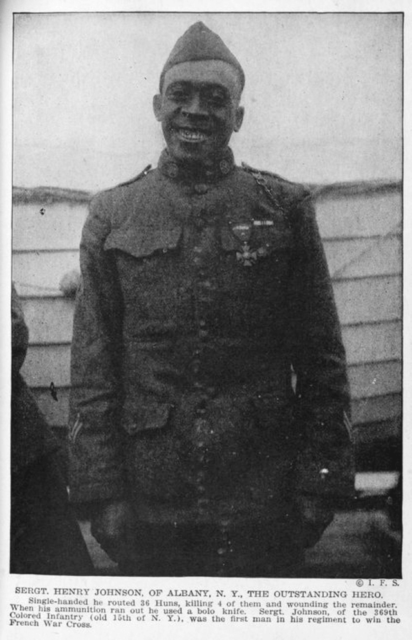

The morning sunrise illuminated the scene, revealing pools of blood, equipment and four dead German soldiers – it’s estimated Johnson inflicted injuries to another 25–30. Word of his legendary stand spread quickly, earning him a promotion to sergeant and the nickname “the Black Death.”

Awarded the Medal of Honor nearly a century later

For his efforts, the French awarded Henry Johnson the Croix de Guerre, one of their highest awards, before sending him back to the US. At the end of the First World War, the Harlem Hellfighters participated in a victory parade, with Johnson upfront. Still, they were not allowed to parade alongside the White troops.

After such an ordeal, many soldiers would return home to a hero’s welcome, which Johnson did, to an extent, but it was a bittersweet achievement. Many publications quickly glossed over his race, or avoided mentioning it at all. He gave his all and returned to a country celebrating his efforts while still regarding him as an inferior citizen.

More from us: John Simpson Kirkpatrick: The ‘Man with the Donkey’ in Galipoli

The final years of Johnson’s life mirrored the first, slipping into obscurity after the war, while receiving disability payments from the US government. It remains unclear how much his injuries affected his later life and job opportunities. He passed away on July 1, 1929 of myocarditis. The full extent of his actions weren’t appreciated until he was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart in 1996 and the Medal of Honor by then-US President Barack Obama in 2015.