Occurring on August 23, 1914, the Battle of Mons was an engagement between the British and the advancing Imperial German Army in Mons, Belgium. The British lost more than 1,600 soldiers in the offensive, while the Germans lost between 2,000 and 5,000 men.

The following are some need-to-know facts about the battle.

First major British offensive of World War I

The Battle of Mons was the first engagement involving the British Expeditionary Force (BEF). It was a subsidiary of the Battle of the Frontiers, where the Allies fought the Germans along the eastern frontier of France and into southern Belgium.

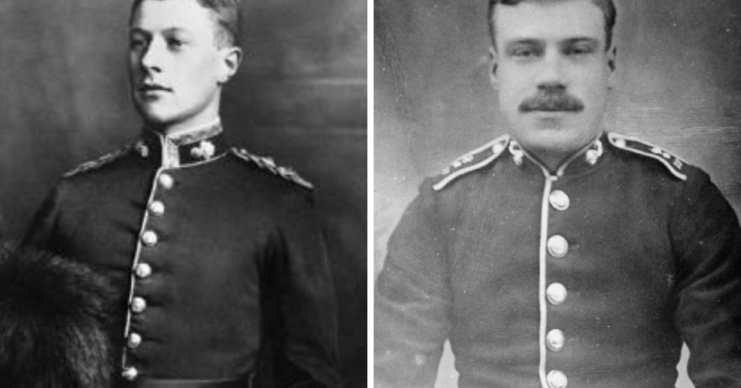

In Mons, the 4th Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers faced the heaviest fighting. For his mettle during the engagement, Lt. Maurice Dease was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross – the first of World War I.

How small was the British Expeditionary Force (BEF)?

At the start of World War I, the British Expeditionary Force had around 90,000 professional soldiers, made up of volunteers and reservists. While it was the best-trained and more skillful military force, it was also tiny in comparison to the French and German armies. Germany had over 3.8 million troops, while the French had about 1.3 million.

Death of the first British soldier of World War I

While the Battle of Mons didn’t begin until August 23, 1914, the first contact between the Germans and the British happened at Obourg on August 21. The 4th Battalion, Middlesex Regiment came across a German patrol and 17-year-old Pvt. John Parr was killed, becoming the first British soldier to lose his life to enemy action during World War I.

British heavy artillery mimicked machine gun fire

The real Battle of Mons began on August 23, 1914, when German artillery began firing on the British. The Germans tried to push across four bridges crossing the canal at Mons, which the British were holding.

They advanced on one bridge in a close column, but this meant they were easy targets for the British riflemen. The latter then fired upon the enemy from more than 1,000 yards away, and the rifle fire was so intense that the Germans believed they were facing machine gun fire.

First Victoria Crosses awarded during World War I

As aforementioned, Lt. Maurice Dease was the first British recipient of the Victoria Cross during World War I. He was leading a machine gun section and, at first, he and his comrades experienced success. However, the Germans quickly moved into an open formation and launched a second assault. This time, the looser formation made the British unable to mow the enemy down, and the Germans were more triumphant.

The British were quickly outnumbered and found it difficult to defend the canal crossings. At Nimy Bridge, Dease, having been shot several times, took control of his machine gun after the rest of his section had been killed in action (KIA) or wounded and continued to fire at the Germans. Once he was wounded a fifth time, he was taken to the battalion aid station, where he died.

Dease was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross. Pvt. Sidney Godley subsequently took over from Dease and covered the retreat, defending the bridge for two hours before running out of ammunition. He then incapacitated the machine gun, before being taken as a prisoner of war (POW). For his bravery, he was also presented with the Victoria Cross.

‘Great Retreat’

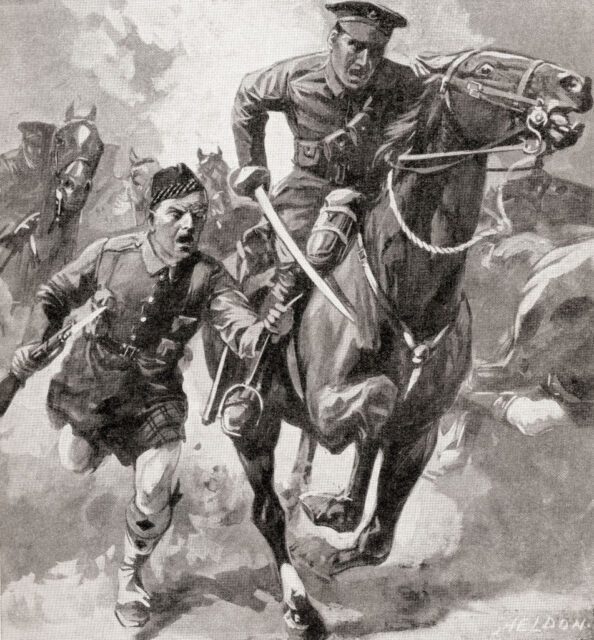

Both sides had new defensive lines through several villages, and the Germans had built bridges themselves over the canals, letting them approach the British Army. The French Fifth Army had also retreated by this time, exposing the British right flank. Unexpected orders to retreat from the defensive lines subsequently came through, and the British soldiers then had to fight sharp rear-guard actions against the Germans.

The losses suffered by the British were high, considering the size of the Expeditionary Force at the time. The 1st Battalion of the Cheshire Regiment declared at evening roll call that they’d lost 80 percent of their infantry. Despite this, at Wasmes, the British managed to hold off the Germans for a further two hours before retreating.

The BEF had no choice but to retreat after being outnumbered. It was a chaotic and confusing scene, as the troops settled into their new defensive lines. On August 25, 1914, a senior officer had even taken “leave of his senses and began firing his revolver down a street.”

The retreat became known as the “Great Retreat,” and it took place over two weeks. Covering 250 miles, the Germans quickly pursued the British, and both sides continued to have skirmishes along the way.

One of the greatest engagements fought by the British

Despite being outnumbered by the Germans and having to retreat, the Battle of Mons was still a big success for the British. They achieved their objective (preventing the French Fifth Army from being outflanked) and that in and of itself was a morale victory for the Expeditionary Force.

The engagement had been the nation’s first on the European continent since the Crimean War, and people were unsure as to how the BEF would do. The troops felt they had had the upper hand during the battle, despite having to retreat.

Even the Germans were aware they’d taken a hit. Novelist and infantry officer Walter Bloem wrote, “We had been badly beaten, and by the English – by the English we had so laughed at a few hours before.”

Battle of Mons was also a success for the Germans

The Germans had managed to gain a lot of ground, despite being initially pushed back by the British, so the Battle of Mons was a strategic success for the enemy. While they’d failed to eliminate the British threat, they were able to cross the Mons-Condé Canal and begin their push into France.

Becoming a mythical engagement

The Battle of Mons gained mythical status in Britain, with the Expeditionary Force experiencing unlikely success against incredibly overwhelming odds.

There’s also a mythical tale that the “Angels of Mons” came to help fight the Allied soldiers. These were angelic warriors, some supposedly phantom longbowmen from the Battle of Agincourt (another unlikely win for the British) and they managed to save the BEF by stopping the German troops from advancing any further.

A cemetery was built on the site of the Battle of Mons

The Germans built the St. Symphorien Military Cemetery at the site of the Battle of Mons, to commemorate both the British and German soldiers who’d died. Originally, 245 German and 188 British soldiers were interred there, with more graves moved there from both sides. Soon, more than 500 soldiers had been laid to rest at the site.

More from us: 20 Photos That Show the Remnants of World War I Scattered Across Europe

Want War History Online‘s content sent directly to your inbox? Sign up for our newsletter here!

There are also several special memorials to different soldiers within the cemetery. Pvt. John Parr is buried there, as is Canadian Pvt. Walter Gordon Price. They were the first and last men on the Allied side to be killed in the First World War.