While the 2026 Winter Olympics turn Cortina d’Ampezzo into a global postcard, the mountains around the finish area are holding a second story—one carved into rock, ice, and silence. The women’s Alpine races are running on Cortina’s Tofane Alpine Skiing Centre, on the legendary Olimpia delle Tofane course.

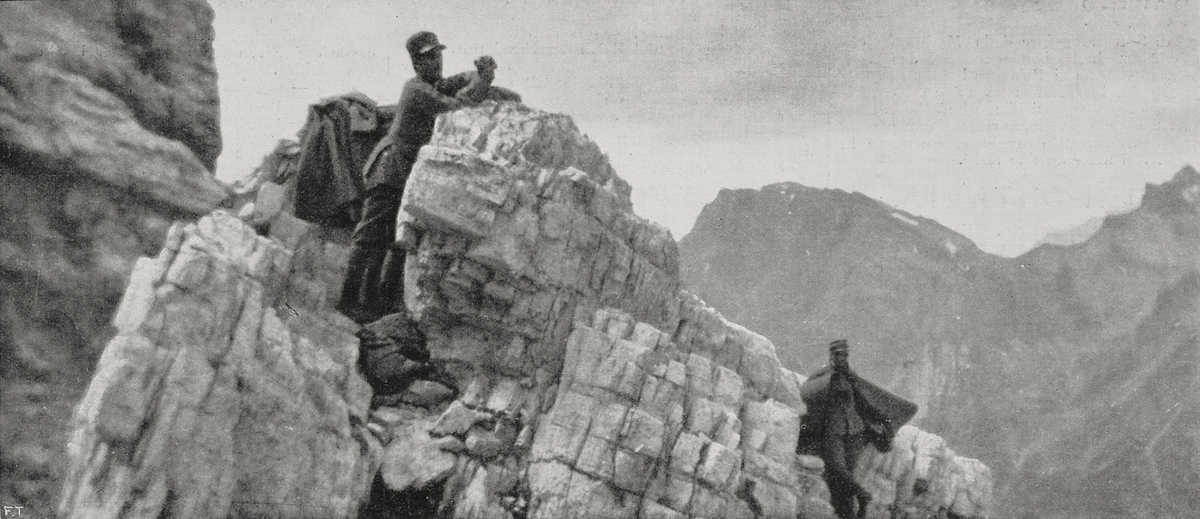

Look up from those bright banners and timing lights, and the Dolomites don’t just feel dramatic—they feel watched. Because just beyond the Olympic corridors, tucked into ridgelines and passes, sit the remains of the “White War”: World War I positions built at extreme altitude, where soldiers didn’t simply fight each other, but fought the mountain itself.

When Snow was the Battlefield

From 1915 to 1918, this section of the Italian Front became infamous for the brutality of the fighting in the Alpine conditions—hence the nickname “White War.” Men lived in high-elevation trenches, dug shelters into cliffs, and tunneled through ice and stone. Cold, altitude, and avalanches were constant threats, and they shaped daily survival as much as bullets did.

That’s what makes the contrast so striking today: the same geography that now hosts elite sport once forced soldiers into a kind of engineering desperation—building underground “fortresses” because the surface was too exposed to artillery and too deadly to hold for long.

Lagazuoi: A Fortress inside the Mountain

If there’s one place that captures the White War in a single breath, it’s Mount Lagazuoi—a peak not far from Cortina’s orbit, where the “battlefield” is literally inside the mountain. During the war, Italian and Austro-Hungarian forces turned Lagazuoi into a rockbound stronghold by carving out shelters, galleries, and firing positions.

Today, those spaces form the Lagazuoi Open-Air Museum, where restored tunnels, trenches, and emplacements can still be visited. You’re not looking at a recreated exhibit—you’re moving through the actual geometry of fear and necessity: narrow passageways, rough stairs, openings cut into cliff faces, and viewpoints chosen because they controlled valleys below.

Fort Tre Sassi: The “Gatekeeper” on the Pass

Then there’s Forte Tre Sassi, a squat, battered fortress near the Valparola Pass that once guarded a strategic approach route. Built around the turn of the 20th century, it was heavily targeted early in the war and later became part of a wider network of preserved Great War sites in the Dolomites.

What hits you here isn’t just the structure—it’s the logic behind it. These forts weren’t romantic castles; they were built to control roads, passes, and supply lines in terrain where a single choke point could decide weeks of fighting.

Monte Piana: An Open-Air Museum where the Lines were Meters Apart

For a different kind of chills, Monte Piana offers a “museum without walls”: trenches, tunnels, and positions spread across a high plateau where the opposing sides sat only a few meters apart in places.

Standing there makes modern speed and spectacle feel oddly fragile. The Olympics celebrate mastery over slope and gravity; the White War sites show what happens when humans try to master a mountain for survival—and the mountain refuses to care.

Why It Feels Relevant in 2026

These places matter now because they remind us that landscapes aren’t just backdrops—they’re archives. The Dolomites are currently framed for the world as Olympic terrain (and NASA has even spotlighted Cortina as a 2026 venue surrounded by steep peaks), but the same cliffs also preserve a century-old lesson about conflict, ingenuity, and vulnerability.

So if you’re watching races this week and thinking, How can anything exist up there?—it already did. Not in luxury lodges or finish-line grandstands, but in tunnels cut by hand, forts battered by artillery, and trenches fought over in the snow. The Olympics give these mountains a spotlight. The White War proves they’ve carried weight long before the cameras arrived.

If you enjoyed this story, you may enjoy the remarkable story of a woman pilot who flew missions in WWI: