One of the most iconic images from the fall of Saigon did not happen in Saigon. It happened at sea where sailors pushed helicopters off their ships. They did so, due to the stubbornness of an incompetent diplomat.

The US began withdrawing troops from South Vietnam in 1973 with a final deadline of 1976. By 1974, however, President Gerald Ford realized they had a problem. Any South Vietnamese who had served the Americans would be targeted by the North Vietnamese when they took over. It was known the South would fall once the US left.

In April 1975 Secretary of State Henry Kissinger received a list of about 1.6 million at-risk people who needed to get out of Vietnam. Excluding Americans, their dependents, and other nationalities who worked for the American government, that left about 600,000 South Vietnamese.

Plans to evacuate the former had been ongoing for years and by the start of 1975, the military was ready to evacuate 8,000 of them.

As they could not possibly take 600,000 people out, the South Vietnamese allocation was lowered to 17,000; those who worked for the US Embassy, plus seven dependents each. Then they took a closer look at the embassy payroll and found the number was nearer 200,000. In the end, however, it did not matter.

By March 1975, the North Vietnamese were in South Vietnam. On April 1, the US Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps began camping out in Saigon’s Defense Attaché Office (DAO) compound to prepare for the evacuation. That was the signal for other embassies to get their citizens out. News agencies began ordering their reporters to leave, as did the CIA. One man, however, said no.

Graham Anderson Martin had been the American Ambassador to South Vietnam since 1973. Despite the advancing North Vietnamese, he was convinced that superior American firepower would deter them. Nor did Martin want people to think the US would run. He ordered his staff to stay put. Brigadier General Richard E. Carey, the Commander of the 9th Marine Amphibious Brigade, went to Vietnam on April 13 to reason with Martin – but it did no good.

Americans were told to stay tuned to the Armed Forces Radio. When they heard Bing Crosby’s “I’m Dreaming of a White Christmas,” they had to get to the evacuation centers ASAP!

Martin held to his convictions until April 28 when the North Vietnamese surrounded Saigon. At 6 PM that evening they bombed the Tan Son Nhut Air Base; right next to the airport. There would be no evacuations by plane – the preferred method as it was the easiest.

Martin had his wife flown out but still insisted the US Embassy staff stay at their posts; except those who had to escort his wife.

The following morning at 7, Defense Attaché Major General Homer D. Smith pleaded with the Ambassador to give the evacuation signal for Operation Frequent Wind; the new name for Operation Talon Vise. Martin refused, demanding to see the air base. Finally seeing little of it was left, he, at last, gave the go-ahead.

“White Christmas” was played on the radio, but it was too late. Thousands of panicked South Vietnamese had jammed the streets to flee further south. Others clogged foreign embassies pleading for last-minute visas. Buses and cars carrying Americans or other Caucasians were mobbed as they were stuck in traffic.

Americans who did get to either the US Embassy or to the DAO compound found the gates shut to stop the tide of panicked Vietnamese trying to get in. With no planes available, there was only one way out – military choppers.

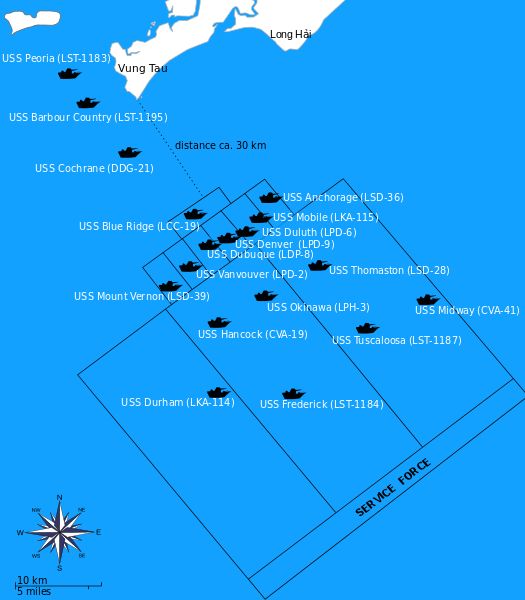

These took evacuees from both compounds out to sea where American warships were waiting. Escorting those choppers were AH-1J SeaCobra Helicopter gunships and other such nasties in case the North Vietnamese tried to shoot them down. They need not have bothered – the North Vietnamese wanted them gone.

For the next 18 hours, 81 overloaded and crammed helicopters piloted by exhausted men ferried people out to the ships regardless of whether they were on the approved list or not. They were not the only ones.

Members of the South Vietnamese military who could fly had similar ideas. Major Ba Van Nguyen had a wife and three kids. None spoke English or had a US visa, but as he served South Vietnam, they were all in trouble.

Nguyen stole a CH-47 Chinook helicopter from his base, flew to his neighborhood, and ordered his family and neighbors to get in. Unable to understand what the Americans were saying on the radio, and knowing the DAO and American Embassy compounds were busy, he took a gamble.

He flew toward the South China Sea. The gamble paid off when he spotted the USS Kirk, but as he approached, the crew on deck waved him away – his chopper was too big. If he tried to land, the rotors would destroy the upper deck and hurt or kill people.

Nguyen hovered over the ship and using sign language, begged the shocked sailors to catch his passengers. Then he flew out to sea, jumped out of his chopper, and hoped a boat would rescue him. One did.

A VNAF Cessna o-1 plane flew over the USS Midway and dropped a note: “Can you move these helicopter [sic] to the other side, I can land on your runway, I can fly 1 hour more, we have enough time to move. Please rescue me. Major Buang, Wife and 5 child [sic].”

Buang was the first person to land a VNAF on a carrier; several choppers having been shoved into the sea. A second followed several hours later.

As more Vietnamese helicopters arrived, the decks on all the ships became full. The servicemen knew what awaited the passengers if they stayed behind. There was only one solution.

Dump more choppers overboard. Several 45 UH-1 Hueys (worth about $10 million) and at least one other CH-47 Chinook ended up in watery graves, as a result.

By the end of Operation Frequent Wind on April 30, some 7,000 people were saved at the cost of two pilots. Thousands more were left behind including Americans who had heard Bing Crosby’s song too late.