The 1944 Nuremberg Raid almost share the same date with the Great Escape in Stalag Luft III. In fact the events are just days away from each other. But why is the other remembered and the other not?

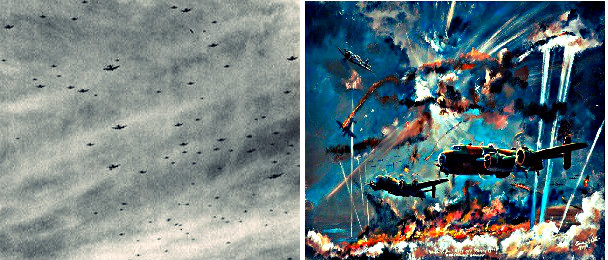

There was so much bloodshed that time even old pros were left stunned. Massacres of whole squadrons happened before the very eyes of their comrades. A number of aircraft blew up mid-air like fireworks in the night as each was packed with three tons of bombs and 1,500 gallons of aviation fuel. Sadly, the blown-up planes also too with them the lives of the crew inside – the lives of seven brave men in each craft.

Pilots of the remaining war planes need not only to dodge enemy night fighters outfitted with the Germans new, secret yet deadly weapon, searchlights and the anti-aircraft guns all firing for them. They also had to steer clear away from the parachutes of their buddies, those who managed to bail out from their fired up planes. There were those who made it to land in one piece. However, the land offered new dangers for them.

That same week, Hitler ordered the deaths of 50 Allied airmen who took part in the Great Escape.

But even in the most horrible times like the 1944 Nuremberg raid, some airmen did not fail to show heroism.

Tom Fogaty gave out orders for his crew to bale out when his controls got busted. But when the flight engineer’s backpack malfunctioned out of reach, he gave his own parachute staying with the falling plane. Miraculously, though, he survived.

Bombarded by enemy planes, the Halifax bomber 22-year-old Cyril Barton piloted was sure not to come out unscathed. His crew had baled out through the confusion but the young pilot continued on to his target. Cyril Barton went on to receive the Victoria Cross for the bravery he showed that night on the Nuremberg raid. But then, he also died that fateful time.

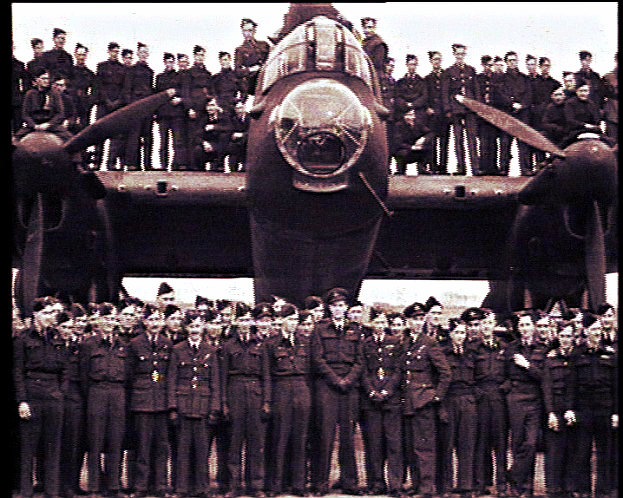

Rear gunner Flight Sergeant Bob Gill was aboard a Lancaster bomber from 35 Squadron which was part of a Pathfinder unit that night of the Nuremberg raid. Their main responsibility was to be in the front line leading the way.

Now 90 years old and with a Distinguished Flying Medal in his name, the WWII veteran summed up the whole campaign in this short sentence: it was a disaster.

And to that, Bob Gill was right. The 1944 Nuremberg raid was the worst night in the whole Royal Air Force’s history and continues to be stamped into many minds until this day. And come the 70th year commemoration of the bloody campaign, these men will once again be remembered anew with wreaths and little messages on the new Bomber Command memorial sitting in a Hyde Park Corner in London.

For one, the family of Victoria Cross recipient Cyril Barton never fails to cherish the memories left by the young wonderful man who was admired by his crew even to their dying days.

Last March 31, his family was in Tyne & Wear to reopen the hospital wing where their brother died from his injuries. The said wing was named Barton Center in honor of the late WWII soldier.

Harold Panton and his family is also one of those who remembered the death of a loved one due to the Nuremberg Raid. Last March 30, they gathered in the disused RAF Skipton-on-Swale Control Tower and held a private service for Harold’s brother, Chris Panton. The service was done at exactly 21:49, the time he took off from the same RAF airfield Nuremberg bound for the last time.

Despite of these private commemorations, however, neither the Royal Air Force nor the Ministry of Defense has shown any inclination of marking the Nuremberg Raid anniversary in any way. For families of those lost airmen who are in as far as Australia and North America, that part of WWII should not be buried and forgotten.

The Nuremberg Raid was a night when over 100 Allied bombers who were on the same mission died. Morning dawned with over 700 men missing and as many as 545 of that number dead. Over 160 of those who participated in the raid went down and became POWs.

Fact is, the Royal Air Force lost more men than in the whole Battle of Britain.

With casualties these high, why did the government chose to skim over the Nuremberg Raid and forget it?

before that fateful night, months for the bomber boys had already been uncertain. Hundreds of war planes carrying thousands of men had already been lost due to the sustained attacks the Allie had been doing on Germany’s industrial interiors.

But WWII was in its fifth year and victory for the Allies was still unsecured. They had to make a secure foothold on the Continent. With the Bomber Command boys taking the war to the enemies, they were an asset to boosting up Britain’s morale aside from the critical strategic importance they had for the army.

Arthur Harris, the bomber boys’ commander-in-chief, still held to his belief that hammering German infrastructure, blocking its supply lines and draining its people’s will was the only way the Allies could gain victory.

But that strategy came with a colossal price. Almost half of the men who served under Harris died – 55,573 from the original 125,000.

Harris, who was knighted but was never given the peerage acknowledged to other wartime officials, later divulged in his writings that if the Navy fought two or three major battles in a war and the Army’s amounted to a dozen, the Bomber Command had to lay over a thousand in the three and half years he served as its commander.

Soldiers and sailors will undoubtedly question his summations but the above statement would surely explain why no one from his senior staff questioned his decision the night of the Nuremberg Raid. He had outlined his plan for the night earlier on and wanted a colossal force – about 700 bombers – to rain down 2,600 tonnes of explosives on the German industrial city.

Nuremberg had been a hub of industrial activities during Nazi Germany with several tank and engine factories based there. Most importantly, it had a symbolic importance to the enemy. Hitler staged many of his rallies here and even called it at one point as the most German of all German cities. Nuremberg had also been left untouched for months.

As pilots and navigators gathered into their briefing rooms, some sighed in relief that they wouldn’t be running into any other deadly air defenses in Europe going to Berlin. Many of them had lost their friends in the recent months to raids in the German capitals.

However, as their new mission was explained, some began to form doubts as they saw the long red line stretched out across the map. Their route took them directly across Germany for 265 miles. Sound judgment would have had them on zigzag route causing confusion to the enemy. But then, that would take more fuel, thus, resulting to carrying lesser bombs.

The other thing that raised the men’s doubts a notch higher was the weather – the moon was almost full and there was little sign of cloud covers. A bright moon meant they were easy prey for the night riders of the Luftwaffe.

Future Chief of the Air Staff Sir Michael Beetham (sky commander during the Falklands War) commented how he expected for the mission to be called off but when it wasn’t they had no choice but to go on.

Commander Arthur Harris, however, laboring based on his view that this was his last try lashing deep into Germany before the shorter nights set in limiting his bombers’ nocturnal range and the coming invasion on Normandy that would shift his attention to France.

He had commanded four diversionary raids which involved 162 bombers to trick the Germans that the Allies were targeting Hamburg or even, perhaps, Berlin. However, the enemy was not tricked for long since the coming force into Nuremberg stretched for 70 miles across the sky in one straight line. The night was clear. It was easy to spot them. And with the RAF vapor trails so clear, the German did really spot them.

John Nichol in his throbbing new account of the Nuremberg Raid, The Red Line, pointed out that upon spotting them, 200 night-fighters Ruhr and the Rhine sped up the sky to meet them. Unknowingly, many of the enemy’s war planes were equipped with something new and deadly. They had new guns which pointed upwards. They could shoot down from below allowing them to hide while firing up the bomber’s exposed underbelly.

Bob Gill later recalled that while it was easy to see up at night, seeing down was a feat. Clearly, the Germans had the upper hand.

German ace Martin Becker nicked six kills just within 30 minutes. The explosions shook the RAF crews. because of the good weather and the full moon, they were offered a good view of other bombers firing up killing off their friends. As Reg Payne, Sir Beetham’s wireless operator, puts it, it was a shock seeing the shower of flames and smoke coming from a dying aircraft occurring in front of his own eyes. What was more disturbing was that he knew there were seven people inside that plane, his comrades, and they were dead.

To add to the bombers’ difficulties were the strong winds blowing them off course. The flying fleet was pushed north to its red line closer to the heavy defenses the Germans put up in Ruhr.

BOAC pilot Jeff Gray, now 91, admitted that he and his crew missed Nuremberg, their target, by miles. When they got to where the German city was supposed to be, they couldn’t see anything. When a searchlight opened, they dropped their load on it and soon, it went out.

Above it all, that Nuremberg Raid in 1944 only did little damage on the city. Only 256 buildings were destroyed with 75 enemies killed – a mere fraction to what the RAF suffered.

60 bombers were destroyed on the way out, 35 got lost upon their return and 11 more crashed into Britain’s own soil.

Cyril Barton only had half of his crew, without radio and flying on one engine when he persisted to drop off the bombs his plane was carrying. He was able to do that but he and his crew had to pass through Germany, Belgium and the North Sea with only the stars as their guide.

They were unable to radio contact with anyone. Reaching British soil, their own side fired out at them forcing Cyril to fly back to the North Sea and look for another approach. He came in again in the coal mine village of Ryhope but unfortunately, ran out of fuel. Doing his best to fly clear away from the miners’ abodes and the pithead equipment, he was able to land. His crew survived but he did not.

Joyce Voysey, Cyril’s sister who is now 79 years old, recounted how her family never wanted him to fly and how her mother never got over her brother’s death.

March 31 saw Joyce and her sister Cynthia visit Ryhope and awaiting them was a warm welcome. Cyril is considered one of the village’s own and is always remembered in their own war memorial.

Bob Gill went on to complete 47 operations before being shot down on his 48th. Jeff Gray expected a scolding for not dropping the bombs he carried right on the target but when he got to the base, he saw that his superiors were just to relieve to see him and his crew alive.

It was indeed a shock throughout the RAF bases hearing Alvar Liddell of BBC announcing that ninety-six of RAF’s aircraft failed to return. That number did not include those that went down within British lands like Cyril’s. However, the remaining RAF bombers had little time to dwell on the deaths and the carnage which ensued at the 1944 Nuremberg Raid.

There was a war they had to continue fighting in.

Tens of years after that disastrous campaign against Nuremberg, politicians and and historians would be locked in a never-ending debate if dropping those tons of explosives on German lands night after night were right or wrong.

RAF shows no signs of commemorating the Nuremberg Raid in anyway. As a matter of fact, the new memorial in honor of those who went down that night was only put up two years ago with the trustees still struggling on the final payment bills of the said monument.

Until now, they need help.

If you want to make a donation that will help pay for the memorial, kindly check this site: rafbombercommand.com