The final years of World War II saw Germany fighting a defensive battle against the Allies. The country’s forces had been pushed out of North Africa and were steadily losing ground in Italy. To reinstate control, they erected a defensive wall spanning the width of Italy, dubbed the Gothic Line.

Inception of the Gothic Line

The Gothic Line resulted from plans to construct a defensive line in the northern Apennine Mountains. This was to protect the Po Valley, which allowed mechanized military units to move easily across the terrain. It also afforded a significant portion of the food supply used by the Axis powers.

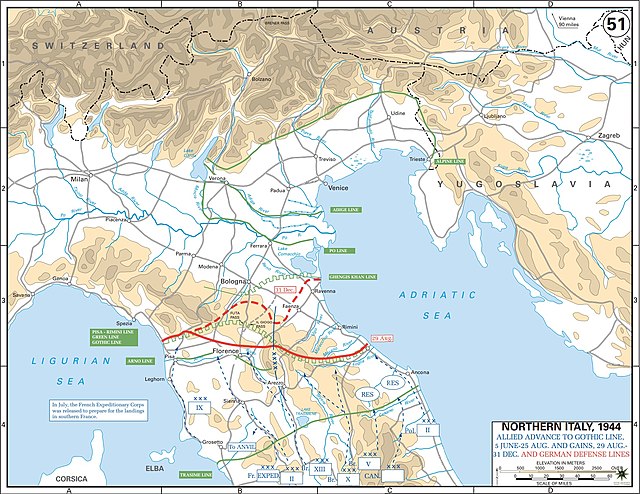

Organisation Todt, Germany’s paramilitary engineering unit, began erecting fortifications in the spring of 1944. With conscripted Italian workers, they produced a 200-mile-long wall beginning at the naval base in La Spezia, across the Apennine Mountains and the Foglia Valley, all the way to the Adriatic port city of Pesaro.

The Gothic Line was reinforced with numerous defensive measures. These included over 2,000 machine gun nests, concrete bunkers, air defense installations, observation posts, artillery positions, anti-tank ditches and casemates.

Allied plan of attack

The original Allied plan for storming the Gothic Line came from Gen. Harold Alexander, Commander-In-Chief of the Allied Armies in Italy. He felt it best to storm the line from the center, where the majority of his forces were already stationed.

Lt. Gen. Oliver Leese, commander of the British Eighth Army, wasn’t convinced, as the Allies had lost their French mountain troops to Operation Dragoon. He felt their strength lay in any tactics combining infantry, guns and armor, which couldn’t be employed in the Apennines. They needed a land assault, so he developed Operation Olive.

The mission called for an Eighth Army attack up the Adriatic coast, to draw reserves from the center. The US Fifth Army, led by Lt. Gen. Mark Wayne Clark, would subsequently launch an assault against the weakened central Apennines, north of Florence and toward Bologna. As the same time, the British XIII Corps would fan out toward the coast on the right side, creating a pincer movement.

To ensure the success of the plan, a secondary mission, codenamed Operation Ulster, would have the bulk of the Eighth Army transferred to the center of the Gothic Line, to trick Generalfeldmarschall Albert Kesselring into thinking the Allies would be attacking there.

Attacking the Gothic Line

The Allies had to contend with the German 10th Army’s LXXVI Panzer Corps, which consisted of three primary divisions – the 1st Parachute, 71st Infantry and 278th Infantry Divisions – along with 51st Mountain Corps units and the 90th Panzer Grenadier and 26th Panzer Divisions on reserve.

The offensive began on August 25, 1944, with the V Corps and the 1st Canadian Corps crossing the Metauro. The Eighth Army then launched its attack against the Gothic Line’s outposts, taking the Germans by surprise. Kesselring was wary of assigning a large force to the area, assuming troops were needed in Bologna, where the Fifth Army would be attacking. After three days, he realized they were needed along the Adriatic front.

The Canadian and British Corps reached the Foglia and continued to defeat the Germans as they pushed further inland. However, just as the Allies began making progress, they experienced pushback from the 1st Parachute Division. This, paired with the area’s poor weather, saw them unable to take the ridge at the river.

The Eighth Army was poised to outflank the eastern portion of the Gothic Line. Their first goal was to neutralize Montegridolfo, while the Polish regiment, under British command, took on the Germans at Pesaro. By September 3, they’d moved inland 10 miles, compromising German defenses along the Adriatic coast. This was followed by a push to overrun Coriano Ridge, which was eventually captured, as well.

The Fifth Army drew up to the Gothic Line on September 12. They aimed to take control of Il Giogo Pass via Monticelli and Monte Altuzzi. Two battalions with the 91st Division’s 363rd Infantry Regiment began their ascent up the western slope of Monticelli and were met with heavy fire. Eventually, the Americans were able to take control and penetrate the center of the Gothic Line.

Poor weather at the Battle of Rimini

The next step was to gain control of Rimini, a German stronghold along the Adriatic coast. After taking Coriano Ridge, the 1st Canadian Corps defeated the Germans at San Fortunato Ridge, making it impossible for them to defend the city. The Allies had succeeded, despite the effort being made difficult due to the poor terrain and weather.

Allied efforts to push through the Gothic Line were continually hampered by poor weather, allowing the Germans to reinforce vulnerable areas. Things weren’t much better in the air, as the Fifth Army’s air support had to contend with heavy fog.

Focus moves to Bologna

By the end of September, Bologna was only 24 miles from the II Corps’ position, while the Po Valley was just 10 miles away from the British troops fighting at Monte Battaglia. The city was intended to become a base for the Fifth Army upon its capture.

On October 1, US Gen. Geoffrey Keyes ordered the II Corps to take up an offensive position against the 4th Parachute and 362nd Grenadier Divisions. The Germans pulled back into the Livergnano Escarpment, preventing the Americans from accessing the area from Highway 65. However, this didn’t stop them from trying to overrun the escarpment. The 91st Division managed to hold the attention of the German forces stationed there.

However, the unprecedented strength of the counterattack put things behind schedule, and the Allies didn’t secure the area until October 13. The Fifth Army then gathered itself for one last effort to take Bologna on October 16, despite being low on munitions. At the same time, other Allied units made efforts to gain control of key roadways – specifically, Highways 9 and 65.

Extension of Allied efforts along the Gothic Line

In November, Alexander extended Allied operations in Italy until December 15, 1944. This began with the 4th and 46th Divisions attacking Forli, a German communications center along Route 67, aided by diversionary efforts by the 56th Division. At the same time, the Polish 5th Kresowa Infantry Division made moves toward Montemaggiore.

The Poles outflanked the Germans in Forli, while, just six miles northeast, the 12th Lancers captured Coccolia, the last German stronghold along the Bidente-Ronco. This was subsequently followed by the V Corps’ capture of Faenza and a brief back-and-forth for Montefortino.

The Fifth Army’s focus was to dislodge the Germans from their artillery positions. These were key to the Germans preventing the Allies crossing into the Po Valley, toward Bologna. Using Brazilian forces and the US 92nd Infantry Division, they attacked these points one by one, but failed to obtain positive results.

Winter weather puts the offensive on pause

By mid-December 1944, word of a German offensive against the Allies in France, Luxembourg and Belgium reached the Italian front. Later known as the Battle of the Bulge, it prevented reinforcements from arriving on the front.

This was made worse by the German 10th Army establishing itself on the banks of the Senio, preventing the Eighth Army from crossing in the increasing winter conditions.

The Germans attacked the Allies on December 26. Codenamed Operation Winter Thunderstorm, it targeted the 92nd Infantry Division, which gave way under the assault and opened a 500-yard gap. The Germans continued with a final attack on the left wing of the Fifth Army in the Serchio Valley.

By the time reinforcements arrived, they, with the help of Italian troops, had captured Barga.

More from us: Kildin Island Incident: When a Russian Submarine Surfaced Right Under an American Spy Sub

Want War History Online‘s content sent directly to your inbox? Sign up for our newsletter here!

After seizing the town, the Germans pulled back, as their mission was complete. With the weather becoming more hazardous, it was decided the Fifth Army’s drive to Bologna would wait until April 1945 and the Eighth Army’s advance would be put on hold.