If there’s one new consistent in the world today, it’s disappointment due to changed plans. But that might not be such a bad thing overall for a person’s psyche, according to Gary Beikirch, 72, an elite former Green Beret Army medic who lives today near Rochester, New York.

Beikirch learned important lessons from a historic self-imposed season of isolation he undertook after coming home from the Vietnam War.

Today, as people around the world wrestle with loss and life-changing uncertainties, the lessons Beikirch learned are more important than ever.

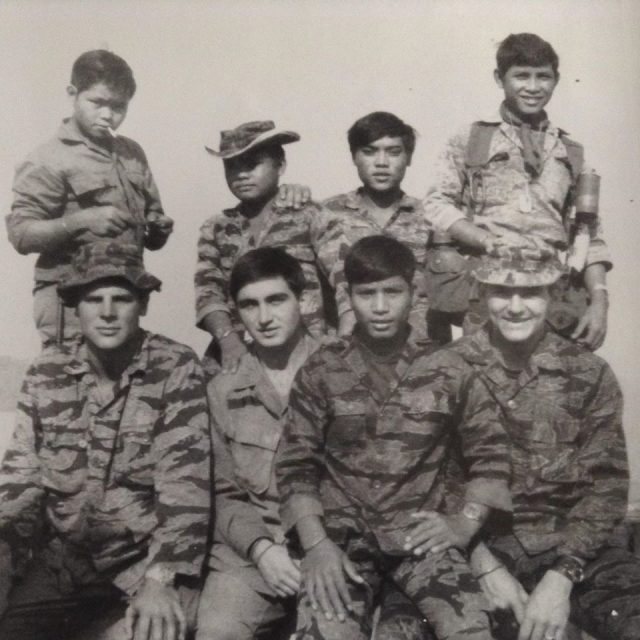

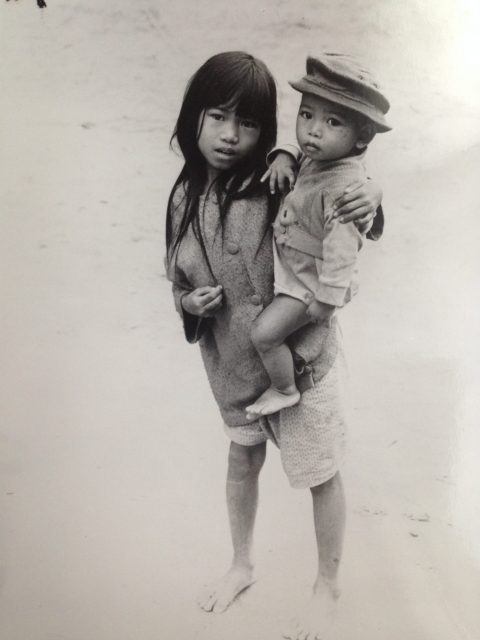

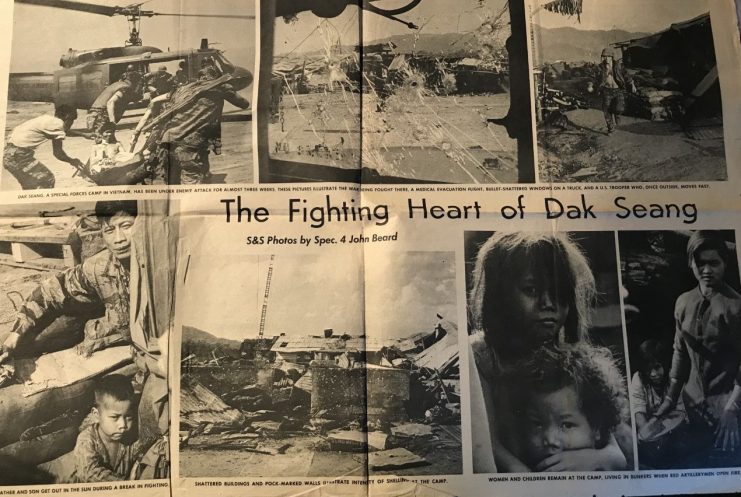

Beikirch was severely wounded during a devastating firefight in Vietnam’s Central Highlands region. On April 1, 1970, he and some 400 Montagnard soldiers and 12 Green Berets were shellacked by enemy fire while trying to protect 2,300 women and children inside a tiny village called Dak Seang.

Some 10,000 enemy soldiers had surrounded the village in secret, intent on wiping it off the face of the map. The Green Berets and indigenous fighters fought back with all they had. Still, they were outnumbered 24 to 1.

Inside the village, the carnage was horrific. Soldiers were getting hit and dying—and so were the women and children.

Beikirch was hit three times in his stomach, hip, and back, and paralyzed from the waist down. His war should have been over. But as the medic lay bleeding on the battlefield, he knew he still had a job to do. With the battle still raging, he called two helpers to his side and ordered them to carry him.

For hours, still under a hail of fire, Beikirch was dragged from person to person as he continued to do his job, administering aide to the wounded, helping anyone he encountered.

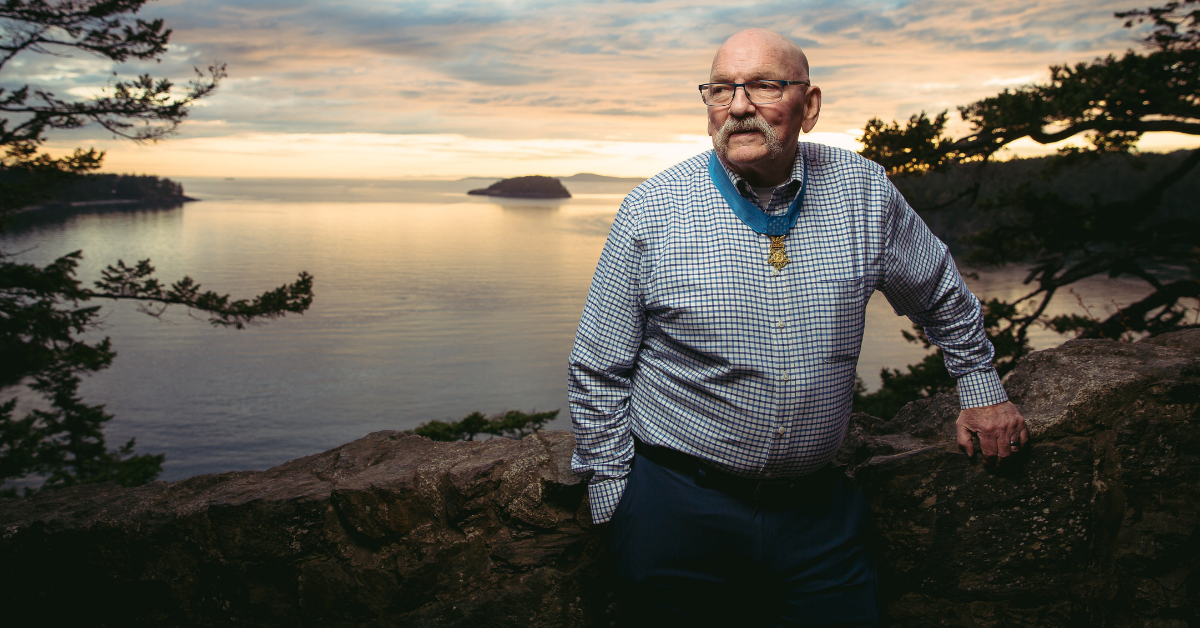

For his selfless actions above and beyond the call of duty, Beikirch would later receive the Medal of Honor, the United States’ highest and most prestigious military distinction for acts of valor.

You would think Beikirch would have received a hero’s welcome and ticker tape parade when he came home. But like so many of his generation of military personnel, that was far from the case.

After being medivacked off the battlefield to a series of hospitals and then flown back to the United States, Beikirch eventually healed in body and learned to walk again. But he was still wounded in spirit from his combat horrors.

The trauma was only compounded when he returned to university. He was called names, shoved in the hallways, literally spit upon, and harassed just for being a veteran.

So Beikirch took a cue from Thoreau. With disappointment mounting and threatening to unravel his tenuous mental and emotional state, Beikirch decided to “drop out” of society.

He grabbed a notebook and his guitar and hiked far out into the craggy, vastly-treed Northern Appalachians.

There, for 18 months, he lived inside a cave. Yes, you read that correctly. Inside his self-imposed mountain seclusion, Beikirch endured two frigid winters.

He bathed in streams, ate army rations, and talked to the walls about the dismay inside of him. It was social distancing of the rawest kind.

To be clear, Beikirch’s disappointment stemmed from responses of fellow citizens who didn’t understand or respect his service, not from missed opportunities while social distancing.

But the solution to overcoming disappointment ended up emerging from his radical change of plans. Only by avoiding people, canceling life as he knew it, and hunkering down inside protective walls, was he buffeted into the person he was meant to be.

His goals were clarified. His vision and perspective were redefined. The same can be true for us, Beikirch said today. Disappointment can actually become a professor, teaching us life’s richest lessons.

For instance, late one autumn during his season of living in the cave, Beikirch hiked toward the summit of Mount Adams. The trail felt slippery.

Early snow nearly froze his gloved fingers. In steep places, he needed to climb boulders hand over hand, and Beikirch initially cursed the obstacles. The boulders were cold and unyielding, surely an impediment to his progress.

Yet when the summit came into view at last, so did a new awareness. As Beikirch looked down the trail from the top of the mountain, he saw how the very challenges he had cursed had actually helped him succeed.

The boulders in his way hadn’t been obstacles after all. During the slippery climb, the boulders had acted as rungs on a ladder. The perceived disappointments had actually given him traction, boosting him to reach his goal.

Later, back at the cave, Beikirch found a serious blizzard brewing. Temperatures plummeted. The wind shrieked. Anxiety welled up within the young veteran, but he chose to stay calm. During Green Beret training, he’d learned not to complain no matter his circumstances.

Complaining only compounded hardship and eroded confidence. So now he simply shook the blood to his extremities, bundled up in his sleeping bag, and hoped for the storm to pass. He couldn’t control the blizzard. But he could control his response.

“If I had chosen to complain, it would have only undermined my strength and motivation,” Beikirch said. “That’s the same for any of us today, too. Complaining only hurts yourself, not to mention the morale of the people around you.

The key is to focus on what you can do—on what you can control. Then you’ll find the determination to go forward.”

Today, as the COVID-19 pandemic continues to impact lives worldwide, Beikirch said he’s comforted by the thought that despite the massive disappointment and life-altering changes, people are pulling together.

When the 101st Airborne Saved Friend and Foe

He admits that dealing with disappointment is seldom easy, even though he learned important lessons and grew from his time inside the cave. He hopes that people will win their mind-and-heart battles by perspective and faith.

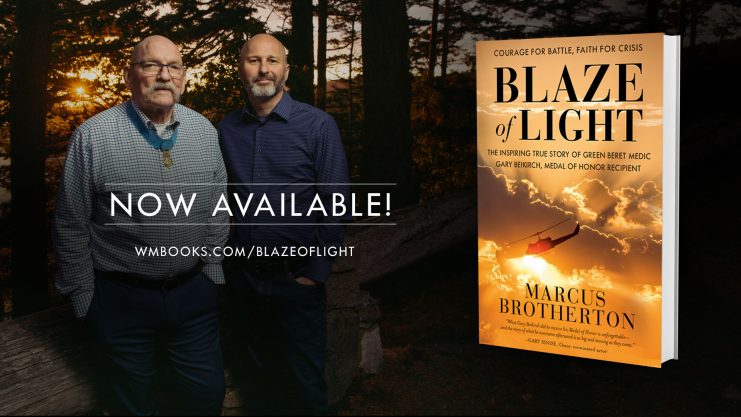

Marcus Brotherton is a four-time New York Times bestselling author.

His newest book, Blaze of Light, is a biography of Medal of Honor recipient Gary Beikirch. You can purchase the book here: Amazon / WMBooks

And he wears the Medal of Honor in tribute to something far greater than himself, with the hope of encouraging anyone who’s ever fought through a battle or sheltered in a cave.