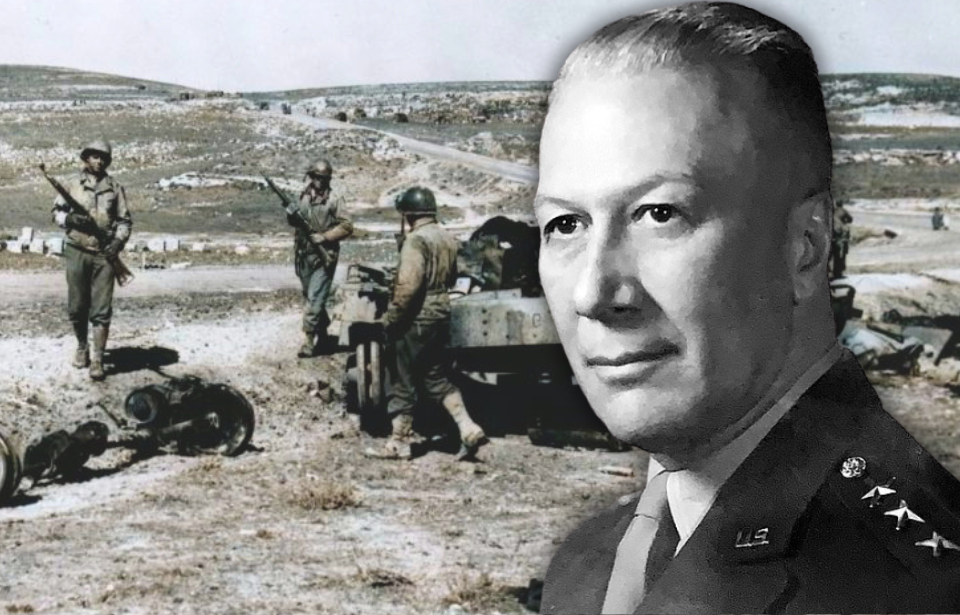

The US military is an institution built on order and service. While the majority who enlist abide by these values, others choose to disregard the chain of command, resulting in disastrous consequences. This is true of Lloyd Fredendall, whose actions hurt Allied operations following the landings in North Africa.

Lloyd Fredendall’s beginnings in the US military

Lloyd Fredendall was born on Fort D.A. Russell, near Cheyenne, Wyoming, on December 28, 1883. His father was a member of the Quartermaster Corps during the Spanish-American War and remained active in the military until his retirement in 1914. He re-enlisted during World War I to supervise the construction of bases in the western United States, and retired at the end of the conflict, having reached the rank of lieutenant colonel.

His father’s connections enabled Frenendall to secure a recommendation from Sen. Francis E. Warren (R-WY) to enter the class of 1905 at the US Military Academy West Point. He was dismissed after one semester. He was allowed to rejoin, but dropped out. While Warren was willing to appoint him a third time, the USMA refused to re-admit Frendendall.

In 1906, Frenendall took the officer’s qualifying exam and scored first out of 70 applicants. A year later, on February 13, 1907, he received his commission in the US Army as a second lieutenant in the Infantry Branch.

Service during World War I and peacetime

After serving in the Philippines and in other assignments, Lloyd Fredendall was sent to the Western Front with the 28th Infantry Regiment. He instructed at the US Army’s schools in France, where he built a reputation as an excellent teacher and trainer.

When World War I came to an end, he was assigned to training duties. He was both a student and an instructor at the US Army Infantry School, and, in 1923, graduated from the US Army Command and General Staff School. He further increased his status within the Army upon graduating from the US Army War College in 1925.

Fredendall also completed multiple tours of duty in Washington at the Statistics Branch, the Inspector General’s Department and as executive officer at the Office of the Chief of the Infantry.

Allied invasion of North Africa

Lloyd Fredendall was promoted to brigadier general in December 1939, and given command of the 5th Infantry Division. A year later, he was promoted again, this time to major general. He was subsequently given command of the 4th Infantry Division, and he held the position until July 1941.

In preparation of the Allied Invasion of North Africa – known as Operation Torch – Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander in North Africa, chose Fredendall to command the 39,000-strong Central Task Force. Once there, he was assigned command of the US II Corps in its advance into Tunisia.

At the time, the II Corps served under the British First Army, commanded by Lt. Gen. Kenneth A.N. Anderson, who found Fredendall to be incompetent, as he used slang when addressing troops and made up confusing codes, instead of using the standard military map grid-based location designators.

Allied advance on Tunisia

In January 1943, German and Italian troops serving as part of Panzerarmee Afrika, under the command of Generalfeldmarschall Erwin Rommel, retreated 1,400 miles westward into Tunisia. Bulked up by reinforcements, a force of 30 panzers broke through at Faid Pass on January 30 and struck the French positions there.

The French reached out to the American forces for help, but the unit was too small and failed to push back the Germans. During this, Lloyd Fredendall remained 70 miles away, overseeing the construction of the II Corps headquarters by a company from the 19th Engineer Regiment.

Obsessed with the possibility of an air assault by the German forces, Fredendall built underground bunkers and anti-aircraft guns at the site. Brig. Gen. Omar Bradley later called the headquarters “an embarrassment to every American soldier,” while Dwight D. Eisenhower used it as an opportunity to remind senior officers of the importance of appearing on the front.

Fredendall refused to heed Eisenhower’s orders and remained at II Corps headquarters. He rarely visited the frontlines, opting to issue orders over the radio, and disregarded advice from those on the front. As such, he split up units and scattered them too far apart to support each other or be effective. This left them vulnerable to an attack by the Axis forces.

Panic at the Battle of Sidi Bou Zid

On February 14, 1943, the Germans launched an offensive at Sidi Bou Zid. Lloyd Fredendall refused to move from his location at II Corps Headquarters. His hilltop defensive positions at Djebel Lessouda and Djebel Ksaira were too far apart to provide mutual support, meaning the Americans could only sit back and watch the German onslaught.

A counterattack was launched the next day, but failed. As such, the Americans abandoned Sidi Bou Zid, but they were cut off at Djebel Lessouda and Djebel Ksaira. The result was a mass panic while the Germans launched Junkers Ju-87 attacks.

Of the 900 men sent into battle, only 300 returned. Demoralized by the defeat and pushed back 50 miles, the Americans fell back to the Kasserine Pass, providing the Germans a pathway through which they could break through Allied rear areas.

Battle of Kasserine Pass reveals Lloyd Fredendall’s incompetence

The Battle of Kasserine Pass occurred from February 19-24, 1943. After heavy fighting, the Germans broke through the pass, but the arrival of Allied reinforcements, paired with issues within the enemy command, stopped the assault. In just 10 days, the US forces had lost 183 tanks and 7,000 troops, of which 300 were killed (KIA) and another 3,000 listed as missing (MIA).

Dwight D. Eisenhower sent Maj. Gen. Ernest N. Harmon of the 2nd Armored Division to report on the fighting. He was also tasked with assisting the Allied commanders – including Lloyd Fredendall – and determining whether he or his 1st Armored Division commander, Maj. Gen. Orlando Ward, should be replaced.

Harmon learned Fredendall and Anderson rarely saw each other and failed to coordinate those forces under their command. He also found out he wasn’t on speaking terms with Maj. Gen. Ward, whom he’d intentionally left out of operational meetings after the pair had a difference of opinion regarding the distribution of his command.

While interviewing field commanders and troops, Harmon discovered Ferdendall was doling out commands contrary to Anderson, causing confusion on the front, and that positions were such that units couldn’t support each other. The field commanders, in particular, felt Fredendall was out-of-touch and a cowardly leader.

Concerned, Harmon requested permission to go to the front and shore up Allied defenses.

Lloyd Fredendall is replaced by George Patton

Following the events at Kasserine Pass, Dwight D. Eisenhower visited II Corps headquarters to confer with Omar Bradley, who’d spoken with division commanders and received the same responses as Ernest Harmon. It was thus decided that Lloyd Fredendall had to be replaced.

While 18th Army Group commander, British Gen. Sir Harold R.L.G. Alexander, informed Eisenhower that he would happily take Fredendall’s place, the latter approached Harmon, who declined, citing it would be unethical to appear to personally benefit from his assessment of Fredendall.

In the end, control of the II Corps was given to Maj. Gen. George Patton, who assumed the position on March 6, 1943. Under his command, the unit was transformed, as he implemented a strict uniform policy and training regiment. The turnaround resulted in a morale-boosting victory at El Guettar, just 10 days after.

Due to the events of the Battle of Kasserine Pass, Fedendall went down in history as one of the most unsuccessful generals of the Second World War. While not completely to blame for the Allied failure, as US troops were largely green and overconfident, his inability to follow the command structure and his withholding of information are largely to blame.

Closing years of World War II

Lloyd Fredendall returned to the United States at Dwight D. Eisenhower’s recommendation. Despite his mistakes, Eisenhower’s refusal to formally reprimand Fredendall allowed him to receive a promotion to the rank of lieutenant general, meaning he was now eligible for three-star assignments, which he duly received. He returned to the US with a hero’s welcome.

Eisenhower’s aide made a report to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, where it was communicated, without elaboration, that the former wished for Fredendall to be reassigned to a training command. This recommendation was followed and Fredenall spent the remainder of World War II working training assignments across the country.

More from us: 34 Miles of Tunnels Were Dug By the British Military Beneath the Rock of Gibraltar

Fredendall continued to serve in the US Army through to the end of the conflict. He retired on March 31, 1946.