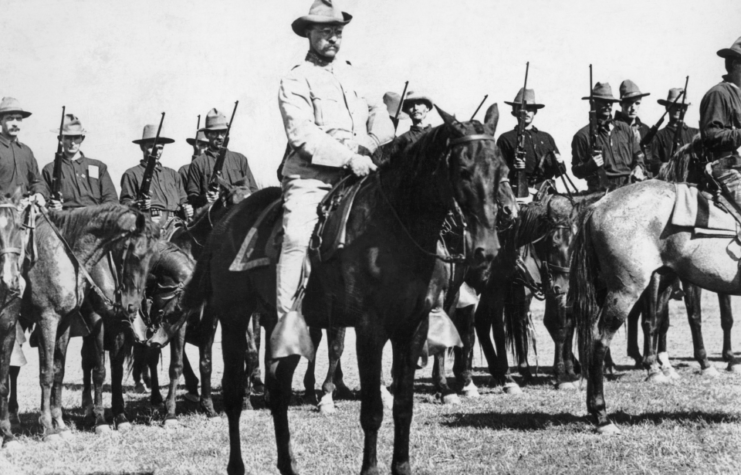

It’s a well-known fact that the United States officially entered the First World War in April 1917, but if it had been up to Theodore “Teddy” Roosevelt, the country would have entered the conflict much earlier. The former US president made no secret of his desire to personally start fighting alongside fellow Allied nations in the trenches – in fact, he tried to accomplish this by offering to raise volunteer troops to fight the Germans on the Western Front.

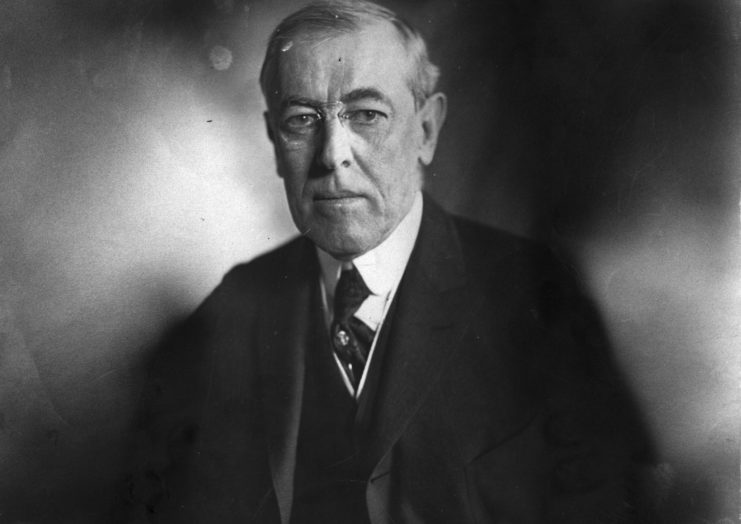

Ultimately, his request was turned down by President Woodrow Wilson.

Teddy Roosevelt wanted America to immediately join the Great War

When the First World War broke out in 1914, Teddy Roosevelt strongly supported the Allied cause and demanded a harsher policy against Germany from President Woodrow Wilson, especially regarding submarine warfare.

The former US president couldn’t believe Wilson did nothing when Belgium’s neutrality was violated, exclaiming, “We [America] should have interfered, at least to the extent of the most emphatic diplomatic protest and at the very outset, and then by whatever further action was necessary.”

Roosevelt believed that early action in the early years of the conflict could have stopped it in its tracks – or, at least, prevented its expansion.

Woodrow Wilson had other ideas

While Teddy Roosevelt wanted to go to war as early as 1914, Woodrow Wilson had other ideas, advocating for American neutrality at the outset of the conflict. During the 1916 presidential election, Roosevelt put Wilson on blast for not entering the war over the sinking of the RMS Lusitania, which claimed the lives of 128 Americans.

Increasingly, Roosevelt saw Germany as an aggressor, meaning the nation should be opposed and punished for crimes committed throughout the conflict. He viewed Wilson’s neutrality as a great moral issue, stating that “more and more I come to the view that in a really tremendous world struggle, with a great moral issue involved, neutrality does not serve righteousness; for to be neutral between right and wrong is to serve wrong.”

Teddy Roosevelt wanted to raise a volunteer fighting force

By early 1917, it was becoming increasingly likely the United States would be entering the Great War. In early 1917, Congress, with support from US Senator and future President Warren G. Harding, gave authority to raise four divisions to deploy to France, very similar to what Teddy Roosevelt had done when he raised the 1st United States Volunteer Cavalry.

Roosevelt’s proposed plan was to lead a volunteer company, including a cavalry brigade, after six weeks of stateside training, followed by “more intensive” instruction in France. The Congressional legislation approving four volunteer divisions did not mention the former president by name, but it was apparent that it was written with him in mind.

According to Sen. Henry Cabot Lodge, “his [Roosevelt’s] presence, there would be a help and an encouragement to the soldiers of the allied nations.”

Forming the volunteer divisions

The proposed volunteer divisions were to be organized and recruited by Maj. Frederick Russell Burnham. On the surface, it would appear that Teddy Roosevelt, even if not mentioned by name, would finally see some action in Europe. Speaking to the power he could bring to allied troops, Henry Cabot Lodge wrote, “He is known in Europe as no other American… His presence there would be a help and an encouragement to the soldiers of the allied nations.”

In Edmund Morris’ 2010 biography, Colonel Roosevelt, the former president’s determination is highlighted as an era of fatalism. “I shall not come back,” he told fellow Republicans in New York when speaking of his hopeful return to the battlefield.

Immediately following news, nearly 2,000 men wrote to Roosevelt every single day, offering up their services to his cause. He was able to recruit former Rough Rider John Campbell Greenaway, as well as Louisiana lawmaker John M. Parker and frontier marshal Seth Bullock, to help lead his charge. It appeared that his reputation with forming the Rough Riders was ready to pay off.

A short-lived endeavor

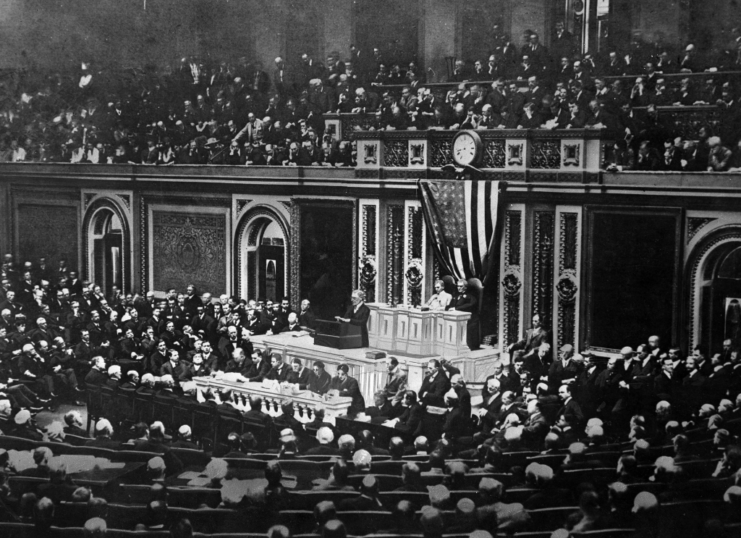

Teddy Roosevelt’s plan to raise a volunteer army was short-lived. On May 18, 1917, Woodrow Wilson signed the Selective Service Act, which gave him the power to conscript men ages 21-30, as well as the option to call up 500,000 volunteers. In a very public, but very polite statement, he announced that Roosevelt’s four special volunteer divisions would no longer be necessary.

In his justification for favoring the draft over Roosevelt’s volunteer divisions, Wilson said conscription would ensure a “people’s army” that was more representative of the nation as a whole.

After the announcement, Wilson sent Roosevelt a telegram, claiming he’d based his decision on “the imperative considerations of public policy and not upon personal or private choice.” The former, however, didn’t buy this and, in 1917, Roosevelt published The Foes Of Our Own Household, in which he indicted Wilson, stating he was largely disqualified to lead a country in its hour of need.

Angered by what he saw as a double-cross, Roosevelt responded in a private letter by calling the president “an utterly selfish, utterly treacherous, utterly insincere hypocrite.”

Teddy Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson’s relationship

In the years following the First World War, there was much discussion regarding the relationship between Teddy Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson.

In his 1958 Pulitzer-prize winning biography, Woodrow Wilson, author Arthur Walworth wrote that the former president thought Roosevelt would recruit the US Army’s best officers to “make up for his own shortcomings.” Other recollections have claimed that Wilson feared Roosevelt would return to America a war hero, allowing him to reclaim the White House.

More from us: How Marie Curie Brought X-Ray Technology to the Front During World War I

Want War History Online‘s content sent directly to your inbox? Sign up for our newsletter here!

Roosevelt was never able to forgive Wilson for denying him the opportunity to raise his volunteer divisions. His sons joined the military and were deployed during the conflict. His youngest son, a pilot, was shot down and killed in July 1918. When Wilson learned of the death, he telegrammed Roosevelt his condolences. The former president died six months later, in January 1919.