During the Civil War, Confederate blockade runners evaded Union blockades set up to prevent war supplies and other goods from reaching the South. They used “the most sophisticated engines that England could put out,” said underwater archaeologist Billy Ray Morris. “They were wickedly fast.”

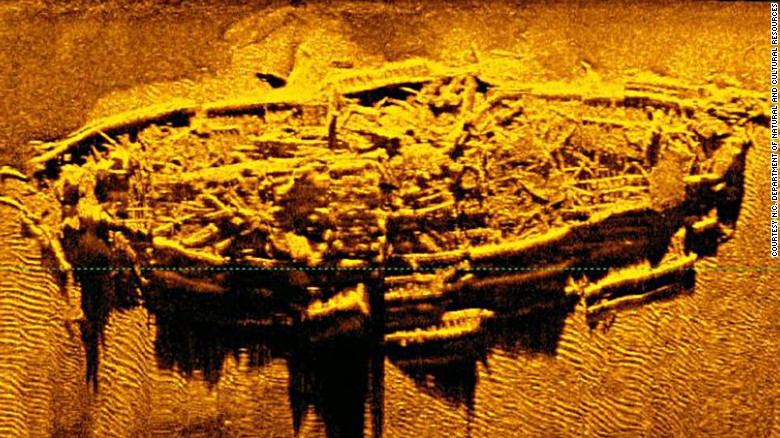

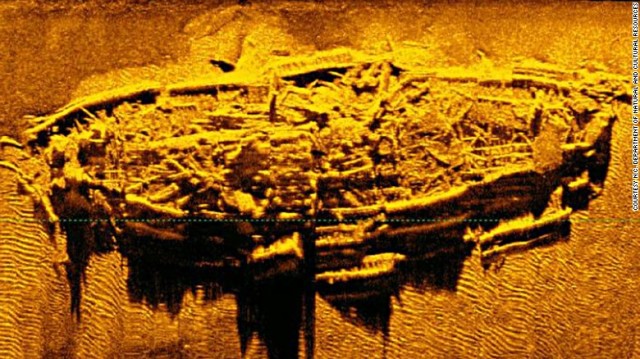

On February 27, an iron-hulled steamer was found 400 yards off the beach near Oak Island in North Carolina. The Civil War-era wreck may be the remains of one of three blockade runners believed to have run aground in the area, according to Morris.

The Agnes E. Fry, Spunkie, and Georgianna McCaw are all known to have sunk in the same area about 18-20 feet deep in the Atlantic. Morris says that the Fry is the most likely match to the newly discovered shipwreck because its length is the closest correlation. Approximately 225 feet of the remains are exposed.

This is the first Civil War-era ship found in the area in decades, about 27 miles downstream from Wilmington, near the mouth of the Cape Fear River. Morris will be diving with others on March 16 and expects to positively identify the ship.

Shortly after President Lincoln announced the Union strategy of blocking Confederate imports and exports, the blockade runners took to the water. It was a good business, carrying fine wines, dresses, and household and war goods, to the Confederate elite and wealthy Plantation owners.

One completed trip could pay for your ship, Morris said.

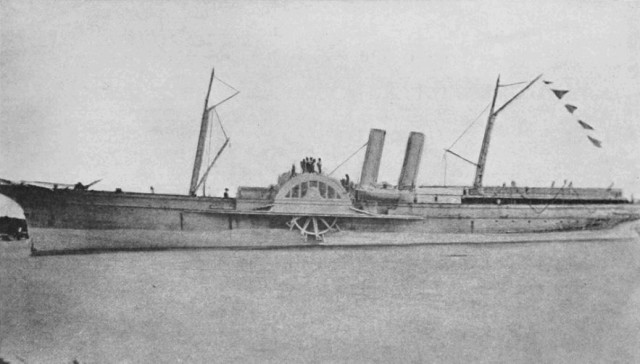

Originally called the Fox, the Agnes E. Fry was built in 1864 on the River Clyde in Scotland. It was renamed after the captain’s wife.

Historians know that the Agnes E. Fry made runs to Cuba and possibly Bermuda and the Bahamas.

Blockade runners typically were unarmed and painted gray to avoid attention. The three ships wrecked in the area of the discovery were all designed to get past the Union blockade to reach Wilmington, a port city and crucial trade entryway.

“Fortifications protected both entrances to the Cape Fear River from the Atlantic and were critical in keeping open a lifeline to the Confederacy,” according to the North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources. With the fall of Fort Fisher, just outside Wilmington, the city was quickly brought to its knees and this greatly contributed to the defeat of the Confederacy.

The Fry crew ran the ship aground to avoid it falling into enemy hands. Salvage operations over the years have removed many of the parts for scrap, including the engines and paddle wheels.

Scientists looking for the three ships had narrowed the search using historical records and a predictive model. They were funded in part by the National Park Service and assisted by the Institute for International Maritime Research.

“These wrecks cover and uncover. Right now, we are in an uncover phase,” said Morris. The wreck currently extends 6-8 feet above the sand and is submerged an equal amount below.

People are welcome to check out the site. “It is against the law to take stuff off of it, but it is not against the law to look,” according to Morris. He does not know what the cargo holds. He’s not as concerned about that as he is about identifying the ship. The only items that will be brought to the surface will be those used to answer questions about the ship.

More research will tell us about the technology used at the time. “She would have been a state-of-the-art blockade runner,” said Morris.

Image from By Unknown – Barnes, James (1911): The Photographic History of The Civil War in Ten Volumes: Volume Six, The Navies, p. 20, The Review of Reviews Co., New York. 1911.Additional source: U.S. Naval Historical Center [1], Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15013043