Ten years after the disastrous defeat of the French Army in its former Asian colony of Indochina, the divided Vietnam once again captured the world’s attention.

While the US was openly supporting the South Vietnamese government, the North, supported by the Soviet Union and China, was posing as an open threat to US interests. What started as a proxy war between military superpowers turned into a US-led intervention after a suspected false flag operation referred as the Gulf of Tonkin Incident which occurred in August 1964.

Just a year earlier, in 1963, a coup was staged in South Vietnam, with the help of CIA, which resulted in an execution of the president of the Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam). President Ngô Đình Diệm was at first appointed as a trusted ally of the United States, but he later became involved in a power struggle that threatened to destabilize the US position in Southeast Asia.

After the coup, the country was basically beheaded and the US seized the opportunity to join the conflict. It became known that the CIA used various tactics to provoke the North Vietnam into direct conflict.

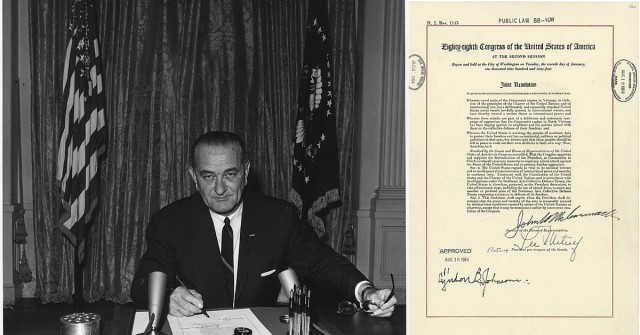

Many historians believe that the events that happened on August 2nd and especially August 4th, 1964, were partly staged to push the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, a document that justifies US military actions in Vietnam, without the official declaration of war against the North Vietnamese government.

Specifically, the resolution authorized the President to do whatever necessary to assist “any member or protocol state of the Southeast Asia Collective Defense Treaty.” This included involving armed forces.

In July 1964, the South and North Vietnam were practically at war due to South Vietnamese commando raids and airborne operations that inserted intelligence teams into North Vietnam, as well as North Vietnam’s military response to these operations. The US was still in an intelligence gathering stage, patiently waiting for the moment to openly invade.

The First Attack

On August 1st, USS Maddox on a covert electronic warfare support measures mission as part of the wider operation called DESOTO, that was intended to gather intelligence concerning North Vietnam. The ship was ordered to keep a safe distance of eight miles from the North Vietnamese shore. Aware of its presence in their territorial waters, the North Vietnamese launched a search party of three torpedo boats.

Intercepted communications indicated that the vessels intended to attack the Maddox, so the American ship began to retreat. On the second day, the patrol boats caught up with the USS Maddox who, in return, fired three warning shots. The Vietnamese responded with a full-scale attack. The attack occurred in waters claimed by the North Vietnam, but the US didn’t recognize this and saw the incident in the context of international waters.

The US aircraft carrier, USS Ticonderoga, which was stationed nearby, launched jets to assist Maddox after the attack had occurred. Maddox suffered only minor damage from a single 14.5 mm bullet from a P-4’s KPV heavy machine gun into her superstructure, even though two torpedoes were fired. After returning fire from its 127 mm guns, the Vietnamese boats started to retreat.

The jets from the Ticonderoga arrived 15 minutes after the warning shots were fired and chased the boats, claiming that they sunk one and heavily damaged the second. The third was reportedly undamaged. After the incident, the Vietnamese claimed differently ― one torpedo allegedly hit the ship, and one jet was shot down. The State Department denied these claims. After the incident, some inconsistencies were evident.

For instance, President Johnson insisted that the Vietnamese fired first, even though reports were filed in which it stated clearly that the Maddox fired warning shots first, which could have been interpreted as attack shots by the Vietnamese. There is also the question of territorial waters. Maddox, when confronted, was approaching Hòn Mê Island, three to four nautical miles (nm) (6-7 km) inside the 12 nautical miles (22 km; 14 mi) limit claimed by North Vietnam.

This territorial limit was unrecognized by the United States. After the skirmish, President Johnson ordered Maddox together with USS Turner Joy to stage daylight runs into North Vietnamese waters, testing the 12 nautical miles (22 km; 14 mi) limit and North Vietnamese resolve.

These runs into North Vietnamese territorial waters coincided with South Vietnamese coastal raids and were interpreted as coordinated operations by the North, which officially acknowledged the engagements of August 2nd, 1964.

The Second Attack

On August 4th, USS Maddox together with the USS Turner Joy was instructed to continue its intelligence operation, this time respecting the North Vietnam’s sea border. During an evening and early morning of rough weather and heavy seas, the destroyers received radar, sonar, and radio signals that they believed heralded another attack by the North Vietnamese navy.

For some four hours, the ships fired on radar targets and maneuvered vigorously amid electronic and visual reports of enemies. Despite the Navy’s claim that two attacking torpedo boats had been sunk, there was no wreckage, bodies of dead North Vietnamese sailors, or other physical evidence present at the scene of the alleged engagement.

President Johnson received a series of cables that didn’t exactly confirm that the skirmish actually happened, but they didn’t deny it either. That same day, Johnson used the “hot line” to Moscow assuring the Soviets that he had no intent of opening a broader conflict in Vietnam, but rather to launch retaliatory attacks concerning the phantom events.

Later it was confirmed that the second incident was caused due to a radar error and that there were no Vietnamese boats present at the time of the incident. Nevertheless, President Johnson held a speech addressing the event directly, in which he emphasized that the battle occurred in international waters, that it was an act of aggression and that the US government is in obligation to help South Vietnam in its war against their communist neighbors.

He gained popular support, and the press distorted the August 4th incident to a ridiculous extent, often guessing and inflating the size of the Vietnamese phantom fleet. The war was imminent.

It was later discovered that US Secretary of Defense, Robert McNamara, was feeding selected information to the President. McNamara was known as a strong supporter of the military intervention, so the second event, which finally led to the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, was God-sent for him. After the war, he openly admitted that there was never a second incident concerning the Gulf of Tonkin events:

“The fundamental issue of Tonkin Gulf involved not deception but, rather, misuse of power bestowed by the resolution.”