Roughly 14,000 ships pass through the Panama Canal annually, but more than half can barely squeeze through the over 100-year-old locks, which are only 110 feet wide. Serving as a bridge between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, the relatively small size of the canal means strict regulations have been put in place to avoid potential incidents.

Known as “Panamax,” the requirements for each vessel passing through have become a major challenge for those on the larger side, particularly naval ships.

History of the Panama Canal

The Panama Canal is considered one of the greatest marvels of the modern world and was one of the most difficult engineering projects ever undertaken. The earliest recorded inquiry into building a canal across the Isthmus dates back to 1534. Just 21 years prior, in 1513, Spanish explorer Vasco Núñez de Balboa was the first European to discover the small channel separating both the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Spain was hoping to seize control of the area, to gain an advantage over Portuguese ships.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, several philosophers and scientists attempted to figure out how to build a canal along the Isthmus of Panama. Even US President Thomas Jefferson suggested the Spanish should build the canal, which would allow for safe passage between the oceans.

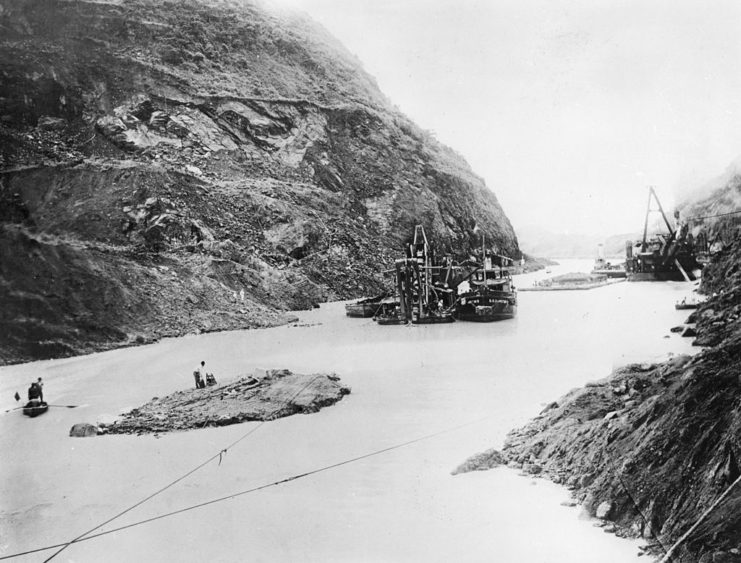

The French were the first to undertake the construction effort in 1881, funded by investors who had already seen the success of the Suez Canal, which opened in 1869. Ferdinand de Lesseps, who led the project, set his sights on the Panama Canal, but vastly underestimated the harsh climate, sprawling jungles and flooding issues along the Isthmus.

de Lesseps intended to build a sea-level canal, just like the Suez, but he’d only visited Panama in the dry season. As such, his men were not prepared for the flooding of the rainy season, which transformed the Chagres River into a raging current. They also had to contend with the surrounding jungle, which was home to venomous snakes and insects (the latter transmitted malaria and yellow fever). Worker mortality rate skyrocketed, with 22,000 men dying from disease and poor working conditions.

Lesseps’ effort went bankrupt in 1889, after spending $287,000,000 million US dollars. Eight hundred thousand investors lost their money, and the project was ultimately abandoned.

In 1903, the United States signed a treaty with the newly-formed Panamanian government, following the Thousand Days’ War. Before the dust had settled and the treaty was in effect, the US brought in engineers to begin planning the canal’s construction. President Theodore “Teddy” Roosevelt famously claimed, “I took the Isthmus, started the canal and then left Congress not to debate the canal, but to debate me.”

Learning from France’s mistakes, the Americans prioritized proper housing, infrastructure and disease management for workers, and after a decade of construction, on August 15, 1914, the Panama Canal officially opened. Its ownership was fully transferred from the US to Panama several decades later, in 1999.

How does the Panama Canal work?

When ships approach from the Atlantic Ocean, two sets of locks lift the vessel up to Gatun Lake, which was artificially created during the construction of the Panama Canal, to make the excavation process easier. It lies 85 feet above sea level, and lowers ships into the Pacific Ocean. The original locks were 110 feet wide, meaning no ship wider than 100 feet could pass through.

In 2007, a third, wider lane of locks was constructed, to increase the Panama Canal’s commercial potential. This allowed the passageway to accommodate larger vessels.

What is Panamax?

Panamax refers to a set of guidelines that restrict the size of ships passing through the Panama Canal. They’ve been in place since 1914 and have shaped how large vessels are built, including those used by the military.

Panamax states that each ship must fit the size of the locks. Vessels must also fit underneath the Bridge of the Americas, and can be no taller than 190 feet from their highest point to the water.

When the wider locks were opened in 2016, a second classification known as New Panamax was developed. New Panamax ships, developed by naval architects, take into account the larger dimensions of the new locks.

How does Panamax affect the US Navy?

According to Forbes, the US military has been slow to take advantage of the wider lock system of the Panama Canal, which has played a vital role in the transit of naval ships between oceans.

The limited size and space meant naval engineers had to cram as much firepower as possible into smaller ships, resulting in a number of vessels passing through with only an inch or two to spare, as seen with Iowa-class battleships during the Second World War. The US also tried to surpass Panamax restrictions with its Midway-class aircraft carriers, which featured a 37-meter beam – four meters over what was allowed.

Even though larger ships can now move through the Panama Canal, thanks to its improved lock system, many US Navy vessels are sticking to the original Panamax restrictions. The future John Lewis-class replenishment oilers and Flight II of the San Antonio-class amphibious transport docks will have beams measuring around 32 meters wide, even though the new restrictions allow for up to 55 meters.

Will bigger ships appear in the future?

Now that the physical barriers around naval innovation have been widened, will the US take advantage of the opportunity to dream bigger, or are other barriers still standing in the way? The answer may not be as simple as you’d think.

More from us: Veterans Saved the USS Batfish (SS-310) By Moving It to a Soybean Field

Panamax not only informs the size of vessels, but also shapes the infrastructure and design processes that allow them to be built. If the Navy wanted to manufacture larger ships, it would first have to overhaul its shipyards. This would also mean other military ports would need to be widened, to fit the larger ships.