On Thanksgiving Day in 1968, while families across America gathered for turkey and celebration, six elite MACV-SOG operatives were waging a silent battle in the dense jungles of Vietnam. Tasked with a mission behind enemy lines, they were up against staggering odds—30,000 North Vietnamese troops surrounded them.

Far from the warmth of home and the comfort of a holiday meal, these men spent Thanksgiving in total darkness, relying on their training, grit, and each other to survive. For them, the holiday wasn’t about feasting or football—it was about staying alive in one of the most dangerous places on earth.

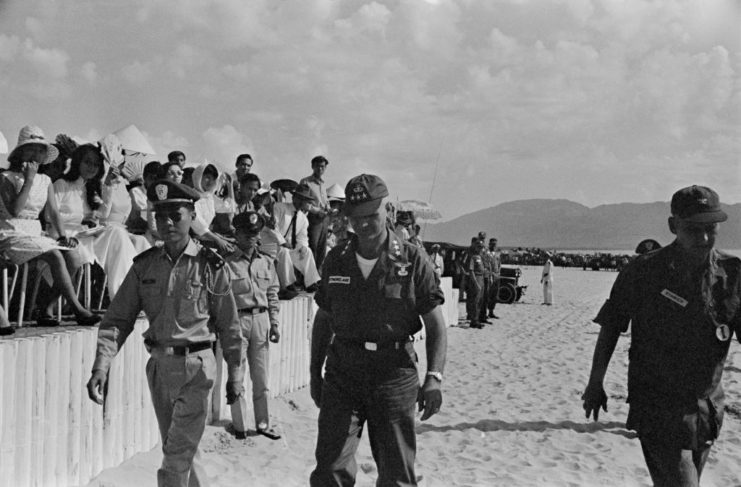

Military Assistance Command, Vietnam

MACV-SOG (Military Assistance Command, Vietnam – Studies and Observations Group) was one of the most elite and secretive units of the Vietnam War. Formed in 1964, it brought together highly skilled volunteers from various branches of the U.S. military—Green Berets, Navy SEALs, Air Force Commandos—as well as CIA operatives and allied local forces.

Their missions were classified and extremely dangerous, often taking them deep into enemy territory across Laos, Cambodia, Thailand, and North Vietnam. This was kept under wraps because the U.S. government claimed its military operations were limited to South Vietnam. To maintain this cover, MACV-SOG members were prohibited from wearing anything that could link them to the United States—no flags, no name tags, no standard-issue uniforms.

A major part of their work involved covert recon and sabotage along the Ho Chi Minh Trail, a vital network used by North Vietnamese forces to move troops and supplies into the South. Disrupting this route was critical—and deadly.

John Stryker “Tilt” Meyer

John Stryker “Tilt” Meyer was one of the fearless men who volunteered to be an operative with MACV-SOG. He initially enlisted with the US Army in 1966, and soon after was accepted to Airborne School, where he was airborne certified.

By the following year, he’d graduated from the Special Forces Qualification Course, eventually becoming a member of MACV-SOG’s Spike Team (ST) Idaho. Meyer detailed much of his time in Vietnam in two books, Across the Fence: The Secret War In Vietnam (2003) and On the Ground: The Secret War in Vietnam (2007).

He was also one of the MACV-SOG commandos involved in the Thanksgiving Day mission in 1968, serving as a reconnaissance leader for a team of six. Aside from Meyer, ST Idaho consisted of four local mercenaries – Sau, Hiep, Phuoc and Tuan – as well as fellow American, John “Bubba” Shore.

30,000 missing enemy troops

By November 1968, U.S. intelligence was still focused on tracking the movements of the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) after the Tet Offensive earlier that year. The offensive, which started in January, involved surprise attacks by the NVA and Viet Cong on cities and towns. Their goal was to stir up rebellion among South Vietnamese civilians and pressure the U.S. to reduce its military presence in the region.

After the Tet Offensive, U.S. officials became alarmed when three NVA divisions suddenly disappeared, leading to an urgent mission to find them. This task was assigned to ST Idaho. The missing divisions—the 1st, 3rd, and 7th—had around 30,000 troops and were part of a larger NVA force of about 100,000 soldiers being closely monitored by U.S. forces. Their sudden disappearance near the Cambodian border raised fears that they were preparing to launch an attack on Saigon.

MACV-SOG’s Thanksgiving mission

The task was simple enough: ST Idaho would enter Cambodia and locate the missing troops, after which they’d relay the information back to headquarters.

On Thanksgiving Day 1968, Meyer and his men waited in Bù Đốp Special Forces Camp, where the MACV-SOG team were delivered a Thanksgiving feast of turkey, gravy, mashed potatoes and cranberry rolls. A helicopter then arrived to deliver the men to Cambodia. This presented its own challenges, as they were only allowed to be brought 10 kilometers into the country via air and would then need to travel the remaining two kilometers on foot.

ST Idaho quickly disembarked the Huey and began their mission, searching for the missing NVA troops in the dense jungle. It didn’t take long for them to notice smoke, which they confirmed was from the soldiers they were looking for. The camp appearing empty, the MACV-SOG commandos began taking pictures and searching for important documents.

It appeared as though they’d successfully completed their mission – and rather quickly. Unbeknownst to them, however, they’d just walked into the middle of a 30,000-strong NVA encampment.

30,000 North Vietnamese versus six commandos

Sau was the first to warn Meyer about the approaching danger, urgently saying, “Beaucoup VC! Beaucoup VC!” Even though Meyer had only been with MACV-SOG for five months—compared to Sau’s three years—he trusted his judgment.

Moments later, North Vietnamese troops advanced from both sides and opened fire. The MACV-SOG team quickly set up a Claymore mine and fell back. The enemy gave chase, but ST Idaho fought back with grenades and trip-wired Claymore mines placed strategically to slow them down.

Help soon arrived in the form of Bell UH-1P Huey helicopters from the U.S. Air Force’s 20th Special Operations Squadron. The choppers laid down suppressing fire with M60 machine guns and M134 miniguns, holding off the enemy. As the helicopter reached the pickup zone, the six men rushed aboard, setting one last Claymore mine at the edge of the landing area as they departed.

Making it out of the Thanksgiving Day mission alive

Meyer later described the mad dash in his book, writing, “We had been moments away from a very violent death and we killed an untold number of NVA soldiers – soldiers who continued to earn our undying respect. I took no pleasure in killing the enemy. It was simply us or them.” They made it, however, with the Huey taking off before the NVA troops could reach them.

More from us: US Navy SEAL? Deadly Sniper? Debunking the Rumors About Mister Rogers’ Military Service

Successful in their mission, although a little worse for ware, the first thing ST Idaho did upon their return to base was visit the mess hall for a well-deserved second Thanksgiving dinner. Soon after, they were tracked down by the MACV-SOG officer who’d sent them on the mission, asking if they would join him for yet another Thanksgiving feast and discuss the mission. Meyer and Shore obliged, debriefing him over the well-earned meal.