Following the Allied success in Normandy after the D-Day landings in June 1944, Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower had managed to push his forces further into Germany’s defensive frontier, using supply problems and the weather to his advantage. All sections of the German Army were struggling in some capacity, with the Luftwaffe suffering fuel supply and veteran pilot shortages.

Hoping to regain aerial dominance, Germany concocted a plan to attack Allied airfields and aircraft, so as to hinder their success along the Western Front. On September 16, 1944, Generalleutnant Werner Kreipe, chief of the Luftwaffe‘s General Staff, was charged with planning such an offensive.

The original plan was developed by General of Fighters Adolf Galland and approved by the commander-in-chief of the Luftwaffe. It detailed assaults on airfields in France, Belgium and the Netherlands, in support of the Ardennes Offensive. This was refined by Generalmajor Dietrich Peltz, who stated a single, coordinated blow would be more effective, as it would prevent engagements between well-trained Allied pilots and the lesser-skilled German airmen.

A number of units were pulled from active service on the Western Front, so they could be involved in what became known as Operation Bodenplatte. The primary aircraft would be Messerschmitt Bf 109s and Focke-Wulf Fw 190s, with medium bomber and night-fighter units serving as pathfinders.

Initially scheduled to occur on December 16, 1944, the start of the Battle of the Bulge, the aerial assault was postponed a number of times over the following weeks due to poor weather. As conditions became more favorable, the decision was made to launch Operation Bodenplatte on New Year’s Day, 1945, as support for Operation Nordwind.

Operation Bodenplatte

Instead of celebrating the dawn of a new year on the evening of December 31, 1944, the Luftwaffe pilots involved in Operation Bodenplatte were instructed to head to bed early, while ground crews prepped their aircraft. In the early hours of January 1, 1945, they took off from base, with 17 airfields as their targets: Ursel, Deurne, Woensdrecht, Asch, Evere, Volkel, Grimbergen, Sint-Truiden, Ghent, Metz, Melsbroek, Ophoven, Eindhoven, Heesch, Le Culot, Gilze en Rijen and Maldegem.

A later review of the plans would conclude that a number were incorrectly attacked.

Maintaining radio silence in the dark and led by the flares from Junkers Ju-88 and -188s, the plan was to strike at dawn, which was equivalent to around 9:20 AM local time, given the time of year. When they launched their attack, the Germans were aided by the element of surprise, as none of the Allied airfields had been anticipating an aerial assault. While British Intelligence had recorded increased Luftwaffe movement and buildup in the region, it hadn’t realized an attack was imminent.

Upon arriving at the airfields across the Low Countries, it became apparent that many Royal Air Force (RAF) squadrons were away on missions, with some locations deserted altogether. This was evident in Grimbergen, where the Jagdgeschwader 26 (JG.26) were met with an empty airfield, the 132 Wing RAF having recently moved to Woensdrecht. The aircraft that remained were protected by flak crews, meaning the Luftwaffe suffered more aircraft losses than the Allies on the ground.

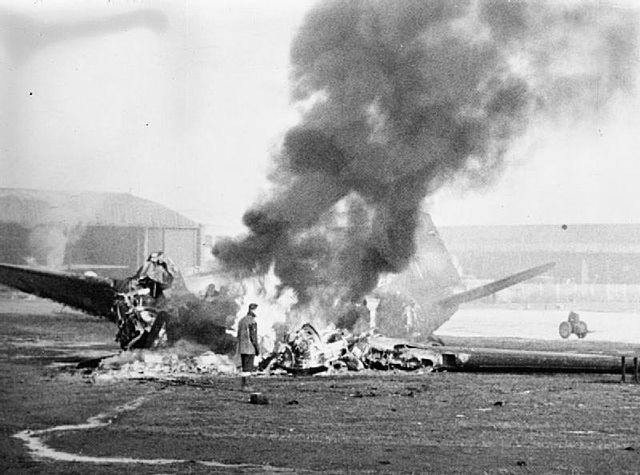

Similarly in Ghent, home to the No 131 (Polish) Wing, a number of Mk IX Supermaine Spitfire squadrons were away on a aerial bombing mission. As such, the German pilots could only target buildings, trucks and a small number of parked aircraft. Among the most heavily-damaged airfields was Metz, where the American 365th Fighter Group’s fleet of Republic P-47 Thunderbolts were strafed with machine gun and cannon fire. This not only damaged aircraft, but caused fuel tanks and munitions to explode.

Throughout it all, the Allies put up a tough fight against the Luftwaffe, inflicting a number of casualties, both human and aircraft. At around 12:00 PM that day, the German pilots left in ones and twos. An assessment of the damage caused showed that, while a good portion of the targets had suffered damage, others had escaped relatively unscathed.

The Allies suffered far less damage than the Germans

While the Luftwaffe claimed Operation Bodenplatte was a success, in terms of surprising the Allies, tactically, it crippled what remained of Germany’s weakening air forces. Of the 850 aircraft that had participated in the mission, 40 percent were destroyed or damaged. Of the pilots charged with manning them, 143 were killed or listed as missing in action (MIA), 70 had been taken as prisoners of war (POWs) and 21 had suffered various injuries. This amounted to the largest single-day loss for the Luftwaffe.

It’s reported that around half of the German aircraft downed during Operation Bodenplatte were taken out by friendly fire. When a post-mission analysis was conducted, it found that only a third of the air combat groups involved – 11 out of 34 – had launched their attacks on time and with surprise.

The Allies, on the other hand, were able to pick themselves up rather quickly after the air raids. Only 250 aircraft were destroyed, while 150 suffered damage that was subsequently repaired. Additionally, only a handful of pilots lost their lives. Within a week of Operation Bodenplatte, a number of aircraft were back in the air, destined for the Ardennes as part of the continuing Battle of the Bulge.

Why did Operation Bodenplatte go so wrong?

After-action reviews of Operation Bodenplatte revealed that the mission had been doomed by systemic flaws long before the first aircraft took off. A significant portion of Luftwaffe pilots lacked proper training, a stark contrast to the veteran aviators of earlier campaigns. Their inexperience proved disastrous—many lingered over their targets instead of striking quickly, making themselves easy prey for concentrated Allied fire.

Poor planning further sealed the operation’s fate. Several flight paths routed German aircraft directly over heavily defended V2 installation zones, most notably around The Hague, where anti-aircraft batteries were exceptionally dense. The maps crews received were rudimentary and imprecise, offering little more than rough sketches instead of dependable navigational guidance. In attempting to protect sensitive information, German command effectively sent their pilots out with almost no usable intel.

Tight secrecy also crippled coordination. Unit commanders were barred from giving complete briefings, leaving many airmen to learn their mission only minutes before takeoff. With so many details concealed, some pilots assumed they were heading out on routine reconnaissance runs—never realizing they were launching into one of the Luftwaffe’s most dangerous and ill-fated operations.

More from us: Operation Chariot: The Daring British Raid on St. Nazaire

Ultimately, the Luftwaffe’s gamble—that Allied forces would be distracted by New Year’s Eve celebrations—failed miserably. Many Allied units had scaled back their festivities, anticipating early-morning sorties, and several squadrons were already returning to base when the German attack commenced. This preparedness enabled a rapid counter, with Allied pilots shooting down numerous attackers and inflicting severe damage on German aircraft formations.