Modern armies have a simple, brutal problem: how do you punch a safe lane through mines and obstacles without putting people in the kill zone? Recently, the UK tested a remote-controlled robotic mine plough designed to push that danger forward—literally—so soldiers don’t have to ride into a minefield.

That same “standoff breaching” logic is exactly what inspired one of WWII’s strangest experiments: the Great Panjandrum, a rocket-propelled explosive wheel meant to crash into Germany’s Atlantic Wall and blow a tank-sized hole through concrete.

Then vs. Now: The Same Mission, Two Very Different Tools

- Then (1943–44): Build something that can carry a huge explosive charge across open beach sand fast, without asking infantry to drag it forward under machine-gun fire.

- Now: Use uncrewed ground systems and remote control to breach minefields and obstacles while keeping operators at distance, like the British Army’s robotic mine plough trials.

The goal didn’t change. The engineering…improved.

Why Britain Needed a Beach-Breaching Monster

As Allied planners stared down the Atlantic Wall, they knew any landing would face concrete barriers, mines, and defensive “dead zones.” The British Admiralty’s Department of Miscellaneous Weapons Development (DMWD)—famous for oddball wartime problem-solving—was tasked with coming up with ways to break fortifications quickly.

DMWD’s brief was specific: create a device that could penetrate thick coastal defenses and ideally be launched from a landing craft, because the sand in front of those walls could become a killing ground.

What the Great Panjandrum Actually Was

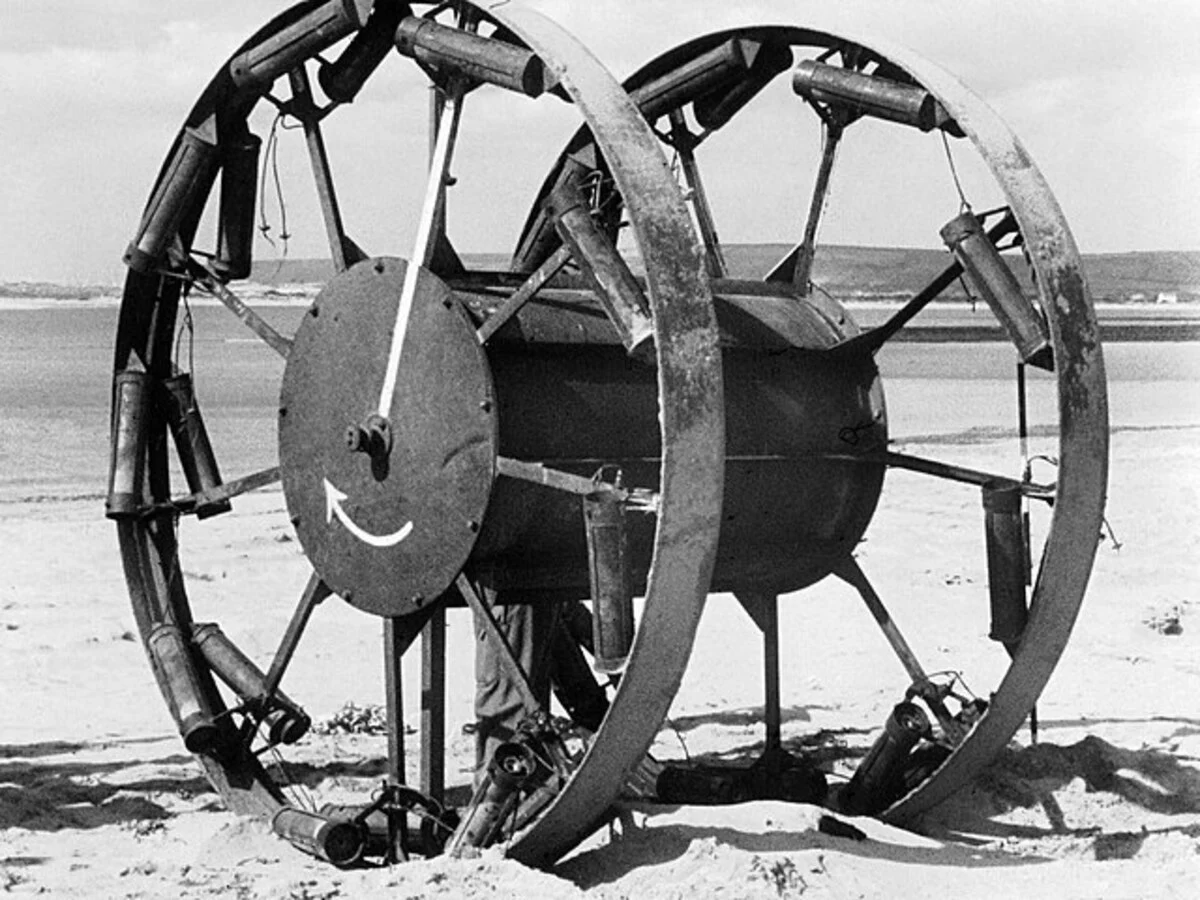

The Panjandrum was not a tank. It wasn’t even a vehicle. It was basically a giant rolling delivery system:

- Two massive wheels, about 10 feet in diameter, connected by a central drum

- The drum was intended to carry over a ton of explosives

- Cordite rockets were mounted around the rims to propel it forward like a spinning, furious Catherine wheel

One calculation behind the concept came from Sub-Lieutenant Nevil Shute (later a novelist), who estimated an enormous explosive load would be needed for a meaningful breach.

On paper, it had everything decision-makers love: cheap-ish materials, terrifying speed, and a promise to solve a deadly tactical problem.

The Trials: When “In Theory” Met “On a Public Beach”

Tests began on 7 September 1943 at Westward Ho! in Devon. The prototype was moved there in secrecy… until the reality of testing on a popular beach kicked in, and crowds turned up anyway.

Early runs used sand instead of explosives, which—given what happened next—was possibly the smartest choice anyone made. The Panjandrum would surge forward, then rockets on one side would fail, detach, or burn unevenly. The result: instead of charging straight at a wall, it would veer off course like a shopping cart with a grudge.

Engineers tried to tame it: more rockets (eventually 70+), a stabilizing third wheel, even cables to “steer” it. But the same problem kept returning—uneven thrust turns a rolling weapon into a roaming hazard. Rockets tore loose; cables snapped; the “weapon” started threatening everyone except the imaginary bunker.

By January 1944, after continued failures, the Panjandrum was effectively abandoned.

What the Panjandrum Gets Right (And Why It Still Feels Modern)

It’s easy to laugh at the footage. But the Panjandrum was trying to do something very modern: remove humans from the most lethal part of the job.

That’s why today’s breaching solutions look less like a rocket wheel and more like remote-controlled engineering systems—like the UK’s robotic mine plough concept, which aims to keep crews out of direct danger while still forcing a path through hostile ground.

In other words, the Panjandrum didn’t fail because the mission was silly. It failed because WWII didn’t yet have the control, sensors, and stability that make today’s unmanned breaching tech possible.