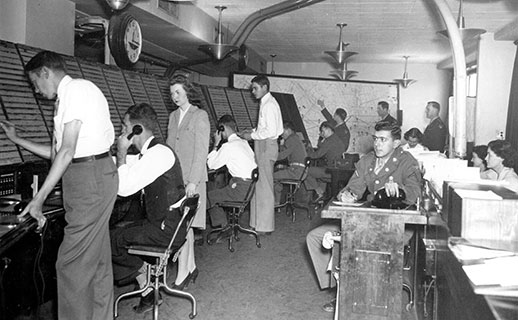

With men overseas in Europe and the Pacific during World War II, women were needed to fill the positions they’d previously had. Many male-dominated industries became inundated with female workers, many of whom paved the way for future generations. One organization to allow women to join was the Civil Aeronautics Administration (CAA), with many taking on roles as air traffic controllers.

United States enters World War II

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, was the catalyst that saw the United States enter the Second World War. Prior to it, US President Franklin D. Roosevelt had been weary about joining the conflict, but an attack on American soil meant he could no longer avoid the inevitable.

With the country at war, the War and Navy Departments placed additional airports under the control of the Civil Aeronautics Administration. This meant taking over operations at local airports, on top of their work with en route airway traffic centers.

With the push for every able-bodied male to join the US military, the CAA enacted a new personnel policy, which stated that “no person shall be selected for employment in the CAA who is eligible for military service.” This resulted in the launch of extensive recruiting efforts geared toward those who were unable to enlist: women and older male civilians.

Training was fast tracked

Civil Aeronautics Administration Administrator Donald Connolly hoped to have 1,200 new air traffic controllers trained by June 30, 1943. The organization set up training centers across the country, including in New York; Chicago, Illinois; Kansas, Seattle, Washington; Atlanta, Georgia; and Fort Worth, Texas. Each was responsible for recruiting, hiring and training its own personnel.

Training began on November 1, 1941. Those eligible had to be between 20 and 45 years of age, have a private pilot’s license, and have 18 months of air traffic control experience or a high school or college education. Training consisted of four weeks of theory, followed by on the job training in a control tower. In all, it took six months to complete.

By late 1942, 40 percent of CAA trainees were women. They were given salaries of $1,800 a year, with an increase to $2,000 upon “satisfactory completion” of their training.

When the Second World War came to an end, many women left the organization to raise their families, as men returned to their pre-war roles. A few stayed on the job, rising through the ranks of the CAA and, later, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA).

Mary Chance VanScyoc

While historians debate who the first female air traffic controller was, many believe it was Mary Chance VanScyoc.

VanScyoc had a life-long love affair with flying, which began in 1935 with her first flight alongside Clyde Cessna. After completing her first solo flight in 1938, she became an aviation student at Wichita State University. In June 1942, VanScyoc began training at the Denver Airway Traffic Control.

Upon starting work that July, her first role was in the “B” board in the Denver tower, which communicated with flight stations, air bases, pilots and airline operators with filed flight plans. The information was then forwarded to “A” board, where it was “plotted on strips of paper.” The lack of radar and computer systems meant there wasn’t a way to verify the information delivered from “B” board. As such, they had to estimate arrival times based on aircraft speed and other variables.

VanScyoc eventually transferred to “A” board, and during her time in Denver earned her commercial pilot’s license. She moved back to Wichita in 1944, where she trained assistant air traffic controllers and earned her flight instructor rating. This led her to focus on being a flight instructor, and she left her role as a controller in 1947.

While life took her in a different direction, VanScyoc never lost her love for flying. She took helicopter lessons and made her first solo flight at 64. She also volunteered at the Kansas Aviation Museum. When she was 74, she flew a World War II bomber, and in 2002 she was inducted into the Kansas Aviation Hall of Fame.

We might never know the identity of the first female controller

While many consider Mary Chance VanScyoc to have been the first female air traffic controller, others argue Mary Gilmore, Ruth Thomas, Marian McKenna Russell or Madelyn Brown Pert likely were.

The reason behind this uncertainty is a dearth in records. When Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the First Supplemental National Defense Appropriation Act to allow the Civil Aeronautics Administration to expand its operation of airport control towers to include those run by the local airport authority, things became rather hectic.

More from us: Lumber Jills: The Women Who Made Up Britain’s Timber Corps

Want War History Online‘s content sent directly to your inbox? Sign up for our newsletter here!

To staff these towers, the CAA hired those who were already employed by the local airport authority. This created scarcity in the records, making it unclear if women were among those hired when the organization took over operations in November 1941.