American interventionism and imperialism is infamous throughout Latin America, and inevitably results in significant anti-American sentiment. Although the U.S. has normally been able to simply ignore this resentment, there have been occasions when it came back to bite them. The Tampico Affair was one such occasion.

America vs. Mexico

In 1914, the idea of American “Big Stick” foreign policy was still very much in effect. In fact, Mexico was already on bad terms with the United States due to previous interventions.

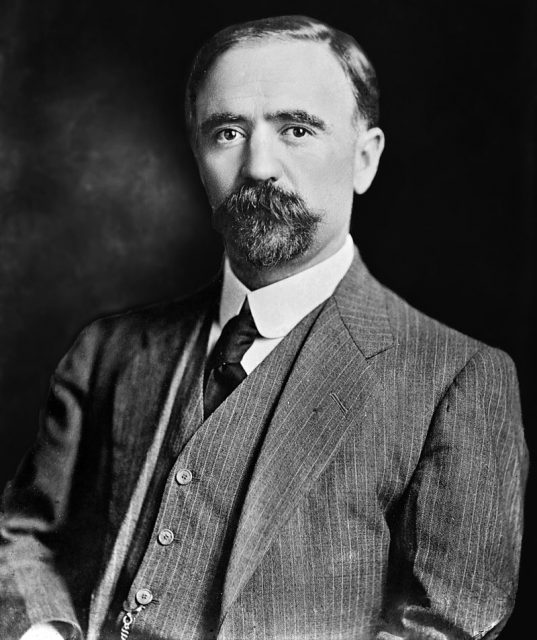

Since the Mexican-American War, the United States had repeatedly intervened, politically and at times militarily, to protect American economic interests. The United States also recognized and backed different Mexican regimes during revolutions. In 1913, the U.S. Government backed a coup against President Francisco I. Madero which resulted in his murder.

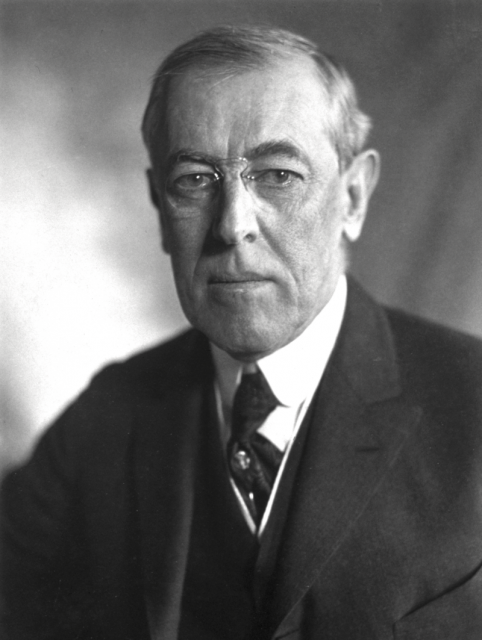

At the time of the Tampico Incident, America had denounced the new Mexican President, Victoriano Huerta. This contradictory foreign policy was a result of differences between the current U.S. President Woodrow Wilson and previous President William Taft.

Mexico’s Civil War erupted again as rebels attempted to overthrow the new regime. Soon, relations between the U.S. and Huerta’s regime became hostile despite that fact that the U.S. helped put him in power.

The Incident

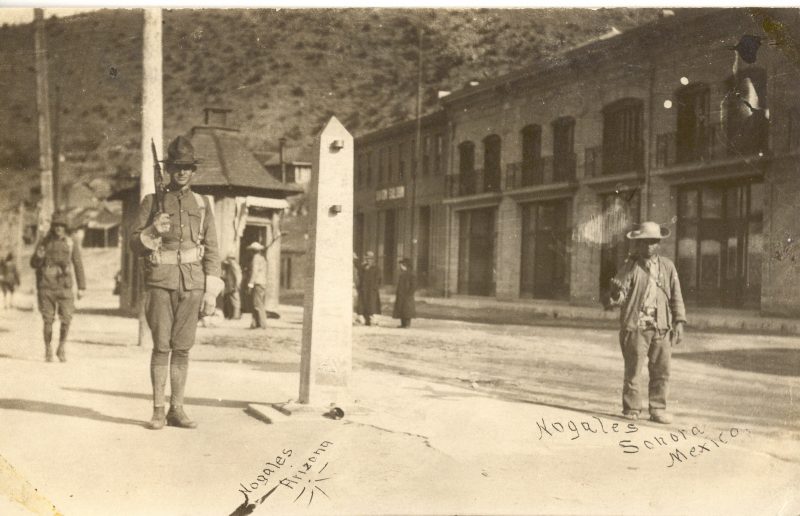

The Tampico Incident occurred against this backdrop, and almost led to a full blown war in 1914. As tensions rose between the U.S. and Mexico, Woodrow Wilson decided to send American ships to protect American lives and business interests. The USS Dolphin was stationed off the coast near the city of Tampico.

Although the city was held by Huerta’s forces, no conflict had taken place between the Americans and the forces holding the city. In fact, the Dolphin had offered several 21-gun salutes to celebrate the anniversary of a great Mexican military victory.

The Dolphin began to run low on fuel, and needed to purchase some from the city. Although the city was besieged by a rebellious army, nine American sailors nonetheless went ashore to make the purchase. They traveled in a whaling ship flying the American flag, and soon landed in an area near the front lines.

As they moved the fuel to their boat, a group of Mexican soldiers showed up to ask them what they were doing. Unfortunately, none of the Americans spoke Spanish, and none of the Mexicans spoke English. Unable to determine why these foreigners were taking their supplies, the Mexicans detained the sailors.

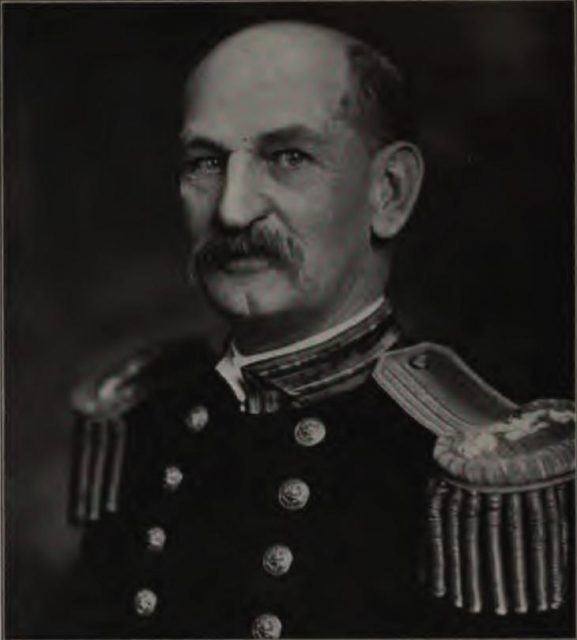

Once the Americans were taken to the police station, they were quickly allowed to leave, and given an apology from the police. It seemed that the incident was over and it was simply a harmless misunderstanding. However, Rear Admiral Henry Mayo was not so forgiving. He demanded that the Mexicans raise the American flag, give it a 21-gun salute, and that Huerta’s national government formally apologize.

Huerta refused, insulted at the thought of raising a foreign flag over his city. Communications broke down between Huerta’s government and Congress. Woodrow Wilson asked for permission to land a military force to take the city, and Congress obliged.

The Attack

In reality, the Americans did not wait for Congressional approval. In fact, the invasion began two days earlier. Woodrow Wilson was really just looking for an excuse to attack Mexico, and now he had it.

After American forces gathered off shore, anti-American protests raged throughout Mexico. Ironically for a fleet sent to “protect Americans and American interests,” their actions led to riots that destroyed American businesses. American flags were burned in the streets.

However, the Mexicans knew they were outmatched, and mostly retreated from the city as the Americans landed. The Americans did not encounter much resistance until they reached the fortified naval academy. During the night of April 21-22, a large number of American reinforcements landed.

The Mexican forces in the academy retreated during the night but, unbeknownst to the Americans, they were replaced by citizens who took up its defense on their own accord. Under the false belief that the city was totally under control, Americans advanced in parade formation towards the building and encountered heavy fire. In retaliation, American ships bombarded the city.

Once the Americans took the building, their casualties numbered 19 killed and 72 wounded. Mexican losses were far higher, at around 150 to 170 soldiers killed and between 200 and 250 wounded. Mexican civilian casualties were not recorded, although civilians were killed in the fighting.

The Retaliation

Although the fighting ended less than a month later with the Niagara Falls Peace Conference, Mexico did not forget what happened. Many Americans were evacuated from Mexico as relations deteriorated, driving the countries further apart.

Meanwhile, World War I was raging on in Europe and the Middle East. Although Mexico had positive relationships with several other Allied nations, they refused to help the Americans. As Americans went to Europe, Mexico reiterated its neutrality. Mexico even economically supported Germany by protecting German businesses and trading with the German Empire.

Read another story from us: Between Two Rivers: Opening Shots of the Mexican-American War

Mexican trade with Germany during the war contributed only slightly to Germany’s ability to keep fighting. However, between that trade and not fighting alongside the United States, Mexico was able to be a thorn in the Americans’ side. The American government never got a formal apology, and dropped the issue at the peace conference.