From the beginning of man’s adventures on the water, the need for retrieving what has been lost to the depths has been part of the bravery and lore of oceangoing lore.

The motivations for men to venture into the hostile and foreign environment below the waves has varied over the centuries, as has the technology involved.

In the case of Edward Ellsberg (1891-1983), salvage work provided not only a venue for his unique leadership and problem-solving skills, but also an opportunity for him to document his involvement in a manner which continues to draw audiences from all walks of life.

No Cure, No Pay

In the business of marine salvage, the term “no cure, no pay” denotes the simple absolute truth involved: if the item is not salvaged, there will be no payment. In recent times, salvage operations on the grounded cruise liner Costa Concordia were initially estimated at about $300 million.

By the time the wreck was raised and finally scrapped in 2017, over $1.2 billion had been invested during the 5-year operation. For civilian efforts, time is not often the driving factor. For military salvage operations, especially during wartime, time is crucial, resources are often limited, and innovation is an indispensable trait for those leading salvage efforts.

Early Beginnings

Like many individuals throughout history, Ellsberg’s beginnings were relatively normal for the times. His childhood spanned several states, and his abilities in writing complemented his love for the sea and his thirst for knowledge. In 1909, his interest in the United States Naval Academy led to his appointment a year later.

Initially, Ellsberg was almost too small to be admitted to the Naval Academy. To meet the weight requirement of 120 pounds, he maintained a diet of milkshakes and bananas which led to him exceeding the requirement by only one pound. It was at the Academy that Ellsberg continued to lead by example and not mere authority, and his academic diligence resulted in his receiving nearly every honor available upon graduation in 1914.

Innovative and resourceful even in his early career, Ellsberg held a variety of positions for which his determination and resourcefulness were best suited. By 1925, he had received several commendations for expediting repairs and production processes. A true seeker of solutions, Ellsberg understood the imperative for safe and efficient naval operations.

Interwar Years and One-Way Submarines

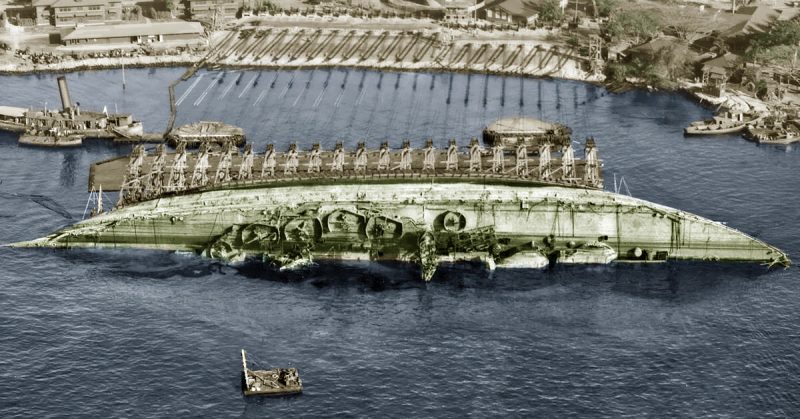

U.S. submarines during the interwar period provided Ellsberg several opportunities to bring his experience and leadership style to their full potential. The first was the loss of the USS S-51, which was rammed by a merchant steamer off the coast of Rhode Island on 25 September 1925.

Volunteering his assistance as soon as he learned of the accident, Ellsberg was soon tasked to lead the salvage efforts. With the safety and welfare of his men first and foremost in his mind, Ellsberg personally conducted dives to the wreck, and refined the tools and processes instrumental in the successful raising of the sunken submarine on 5 July 1926.

The loss of the S-4 in 1927 echoed the circumstances of the S-51 – accidental ramming by a surface ship off the New England coast. Rushing to the scene once again, Ellsberg provided support and assistance for the month he was attached to the operation. Though he was not present for the raising of the submarine on 17 March 1928, many of the men involved were part of his team in raising the S-51 and the techniques they used were the effective and familiar ones he had pioneered two years earlier.

As one of the growing number American military personnel who were increasingly critical of American isolationism in the 1930s, Ellsberg resigned his commission in the Naval Reserves in 1940. Claiming the U.S. was unprepared for entry in the inevitable war against Germany and Japan, Ellsberg and many of his contemporaries were quickly proved correct in their grim forecasts.

Massawa

Upon receiving news of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Ellsberg immediately sought to return to active duty and offered his services in the salvage efforts in Hawaii. Instead, he was sent to Massawa, Eritrea in March 1942. There, the Italian forces had completely and maliciously trashed the port prior to surrendering to the British.

Massawa’s facilities were vital to the Allied efforts in the region: Alexandria was on the verge of being lost to German advances on land, and Cape Town’s distance from the Mediterranean rendered it ineffective as a suitable repair facility for Allied warships.

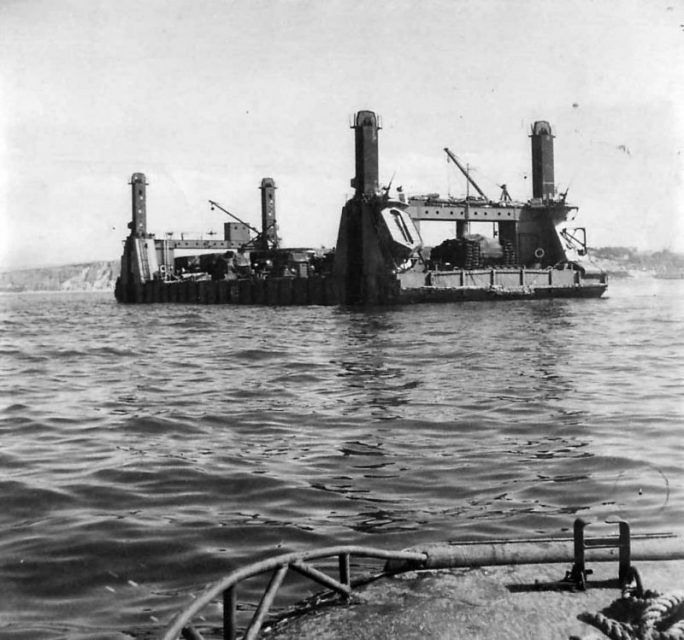

Massawa had been effectively wrecked. Forty ships were scuttled in and around the harbor, the floating dry docks were sabotaged prior to being sunk, and all support equipment and repair facilities in and around the port were almost entirely destroyed or disabled.

With very little in the way of immediate support, Ellsberg managed to rally what personnel and equipment he could and, despite the seemingly intentional bureaucratic obstructions from local British and American leadership, they managed to scavenge, steal, and repair what they could.

Ellsberg’s exploits at Massawa proved to be inspirational to the point of near incredulity. His men repaired ships faster than expected, with unconventional techniques, using equipment in ways never considered. And it was all done with a growing number of men that others had cast off as “undesirable” or “unmotivated.” Their results reflected Ellsberg’s commitment to the mission and his men, and by December 1942, Massawa was operational and effective.

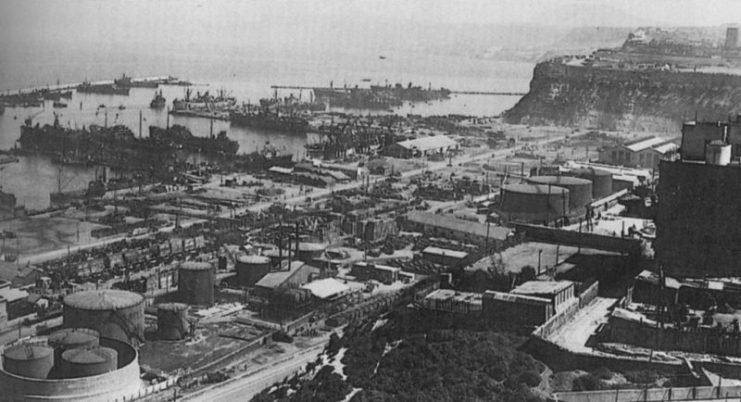

Oran

Transferred to the port of Oran, Algeria, Ellsberg found the port in a similar condition to Massawa. The Vichy French forces had scuttled 27 ships, with some blocking the entrance of the harbor. The equipment on hand was old and well-used, and the available manpower was limited to fifteen divers, mechanics, and assistants.

Again, bureaucratic inefficiency ruled the operations: the different Allied commands insisted on priorities often at odds with each other. Undaunted, Ellsberg continued as before, frequently pausing his work at the harbor to head out to sea as a sort of mobile troubleshooter and damage control master. While he excelled at both monumental tasks, his age proved to be his only major obstacle.

Normandy

At 52, the stresses of Ellsberg’s efforts compounded with the environmental extremes in Africa resulted in his reassignment to New York in 1943. Within 14 months, however, Ellsberg grew anxious to be placed closer to the front, where his skills would find better direct application.

Sent to England less than 2 months before the Allied invasion of Normandy, Ellsberg proved to be vital in the preparations to deploy artificial harbors on D-Day.

These were to be created shortly after the invasion began, for the sole purpose of providing the crucial Allied logistical beachhead on the European continent. Riding across the English Channel aboard a massive concrete breakwater being towed in the wake of the invasion forces, Ellsberg continued be an indispensable asset to the war effort.

Providing organizational assistance and his considerable engineering expertise, he helped expedite the reorganization of the logistical assets on the beaches of Normandy. Later, he became involved in scavenging enough material from one wrecked artificial harbor to guarantee the operation of the other.

Later Years

Leaving the Navy for the final time on 3 April 1945, Ellsberg turned his attention toward consulting and the task of documenting his experiences during the Second World War. In total, Ellsberg authored 17 books, ranging from fiction to non-fiction, before his death on 24 January 1983. Largely overlooked by historians, Ellsberg’s writings chronicled his experiences and attitudes on the topic of marine salvage in a manner which has no equal in naval literature.

Read another story from us: Pearl Harbor Survivor – The USS California “Prune Barge”

However, he had a dim view of being considered as an absolute authority in his field: “For I didn’t consider myself to be an ‘expert’ in anything and besides I had a very low of opinion of ‘experts’ anyway. ‘Experts’ are people who know so much about how things have been done in the past that they are usually blind to how they can be done in the future.”