There are many misconceptions about the medical treatment received by soldiers during the Civil War. Contemporary newspapers often carried exaggerated tales and horror stories of amputations being routinely carried out without anesthesia.

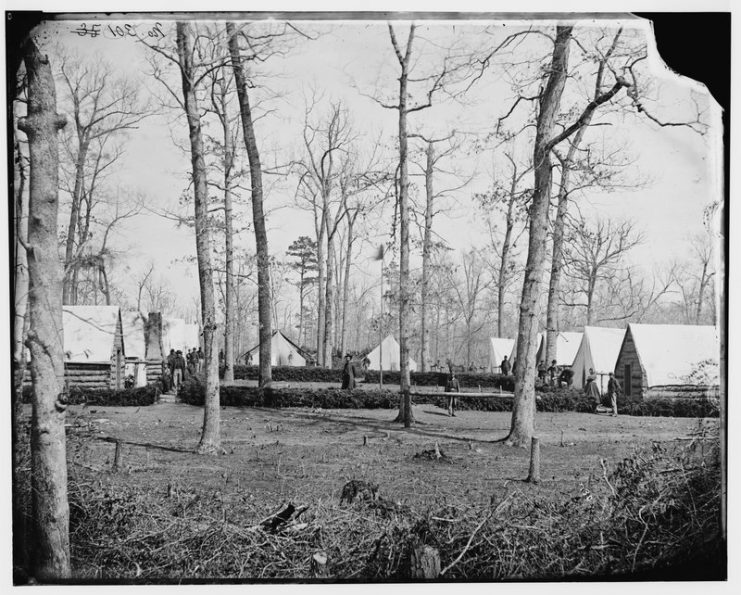

Given the limited medical knowledge available and the pressure under which doctors and nurses had to work, the medical care was probably as good as it could have been under the circumstances.

Because of the sheer numbers and complexity of treating the wounded, doctors working on the battlefield often developed new techniques and treatment. They were working in such extreme conditions that they were forced to think “outside of the box.” This resulted in new ways to approach a problem.

A significant number of these medical breakthroughs came about during the Civil War.

Amputation

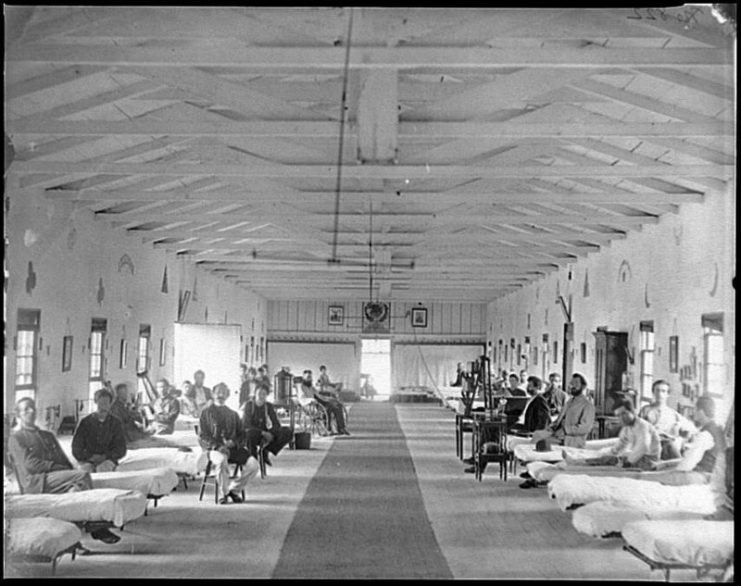

Seriously wounded limbs were difficult to treat. Most of the remedies used were ineffective at either promoting healing or combating infection which was often the cause of death.

Treatment of these wounds was also time-consuming. When there were large numbers needing treatment, such as after a major battle, there was no way of providing care to everyone.

Amputation of the limb was initially seen as a last resort but, if done properly, it could actually lead to a reduction in mortality rates. Despite being brutal, it saved many lives.

The procedure could be completed in around six minutes by an experienced surgeon. The patient was given anesthesia in the form of a chloroform-soaked handkerchief place over his nose.

As surgeons did more amputations, they were able to refine the process and save more lives. They learned that results were best when they cut as far from the heart as possible. They also avoided cutting through joints.

It is estimated that around 25% of patients died as a result of the surgery, while with the older methods only 25% survived.

Improvements to administering anesthesia

At the beginning of the Civil War, the standard method was to use a cloth soaked in chloroform. But chloroform is extremely volatile, and its active ingredients evaporate very quickly. As a result, a lot of chloroform was needed to ensure the patient got enough to knock him out.

Administering chloroform in this way meant that a lot of the chemical was wasted. This is bad enough at the best of times, but during war when everything was in short supply, it was disastrous.

The solution to this problem led to the first inhaler being invented. A small sponge soaked in chloroform was placed at the narrow end of a cone and the wide end put over the patient’s mouth and nose.

Because delivery was more direct, less chloroform was needed. Instead of the standard two-ounce dose, only half an ounce was required to get the same result. Consequently, more patients could be treated with the limited supplies available.

Chest surgery

Chest wounds were among the most difficult to treat on the battlefield, with only 8% of soldiers surviving. Fortunately, a young medic named Benjamin Howard took an interest in helping these patients where other doctors simply gave up.

Howard got to the root of the problem. He understood that it was not the wound but its effect on the lungs that was fatal. Such injuries are referred to as sucking chest wounds because the wound was a hole in the chest which allowed air to travel into the lungs. This usually led to a fatal lung collapse.

Howard treated such injuries using layers of bandages and an ointment called collodion which forms a seal when dry. This made the chest airtight again, allowing the lungs to function normally.

Howard’s new procedure resulted in four times as many soldiers surviving their chest wounds. It was soon adopted as a standard procedure, saving many lives.

Use of quinine to prevent malaria

Many soldiers’ deaths were due to diseases which became more prevalent during the war. The battlefield created the perfect conditions for infection to spread and for parasites to thrive.

One of the most frequently encountered diseases was malaria. It was particularly common in states along the Mississippi River Valley, New Orleans, and Arkansas where rates were 75% higher than average.

At the time, doctors had little understanding of the disease. They were not aware that it was carried in the saliva of mosquitos and transferred through mosquito bites.

The real breakthrough was the discovery by William H. Van Buren in 1861 that the disease could be prevented by taking quinine as a protective measure rather than waiting until symptoms of the fever began, by which time it was often too late.

Quarantine

Another major killer was yellow fever. This disease was also more prevalent in the south where conditions encouraged its spread.

Again, medical knowledge was limited, and no one knew what caused this disease. The most doctors could do was to observe patterns and try to understand when it appeared and under what conditions it spread.

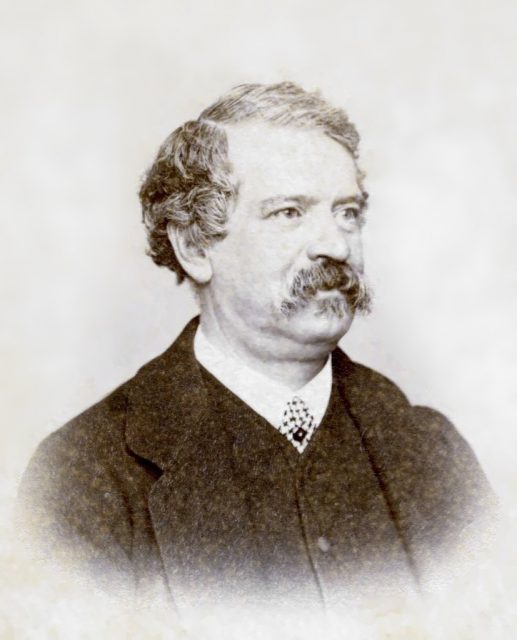

It was noted that the fever seemed to get worse when a new ship arrived at a port. Yellow fever became known as the strangers’ disease because it was often seen in people who had just arrived off a ship.

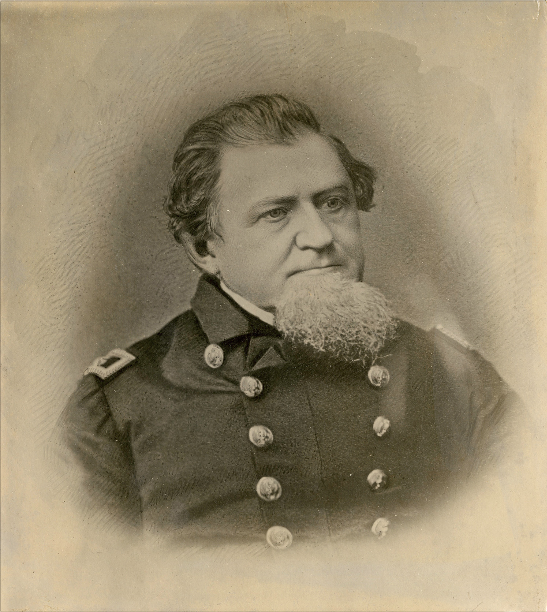

Jonathan M. Foltz, a naval surgeon, was given responsibility for keeping Louisiana free of yellow fever. He was given permission to let only those he considered fit come ashore. He was offered an enormous salary of $1,000 per month but was told he would lose it if there was a single new case.

Read another story from us: Ambroise Paré – 16th Century Surgeon and Father of Military Medicine

Foltz decided that every ship had to wait 40 days and stay at least 70 miles offshore before anyone could disembark. As a result, Louisiana became almost free of yellow fever, and the practice of quarantining became used widely to control infectious diseases.

Very little good comes out of war. But it is encouraging to know that the foresight and ingenuity of doctors and surgeons, serving under the most challenging circumstances, have left such a remarkable legacy behind.