The British occupation of India was a time of dark deeds and extraordinary characters. Few left a more unusual legacy than John Nicholson.

Irish Origins

John Nicholson was born on December 11, 1821 in Ireland, which was then entirely under British rule. His father, a doctor who worked at the hospital in Dublin, died when John was nine, which led the family to move back to his parents’ hometown of Lisburn.

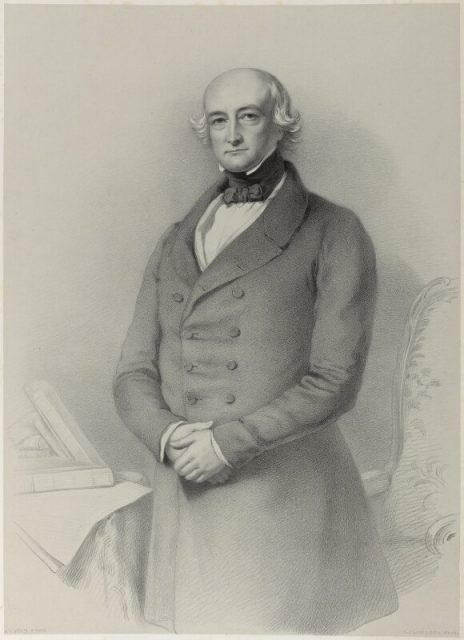

Nicholson’s uncle, Sir James Weir Hogg, was a successful lawyer for the East India Company. He had worked in India, where the Company effectively ran large parts of the country as its own private fiefdom.

Sir James supported young John’s education and then found him a position as a cadet in the Company’s Bengal Infantry. In 1839, at the age of 17, Nicholson set out to pursue a military career in India. It was a career that would consume the rest of his life.

Soldier and Administrator

Nicholson arrived just as the First Anglo-Afghan War was beginning. He soon gained experience in fierce fighting against the Afghans.

Over the winter of 1841-2, Nicholson was part of a British garrison besieged by the Afghans at Ghazni. After the garrison’s surrender, he spent months living as a prisoner in a filthy, lice-infested cell.

After being released, Nicholson returned to military service. He learned to speak Urdu and was assigned to a field force being prepared to fight the Sikhs. He took part in the First Anglo-Sikh War as a junior officer.

By the end of the war, Nicholson had gained the attention of Henry Lawrence, a senior officer and administrator. Lawrence nurtured a skilled group of administrators who took on the role of political officers, governing parts of occupied India.

Nicholson became one of these men, fulfilling the roles of tax collector, diplomat, judge, and police commander all rolled into one.

A Harsh Governor

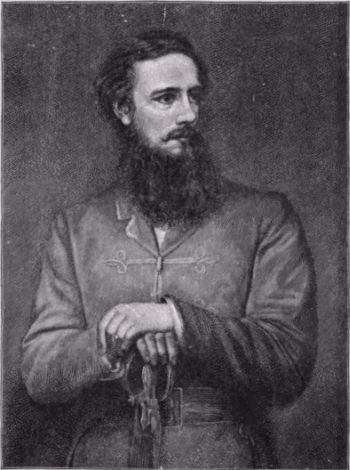

Nicholson developed a fearsome reputation. Angry and authoritarian, yet even-handed and honorable, he earned the fear and respect of the people he governed. He wasn’t afraid to get his hands dirty.

When a jihadi came to kill him, he shot the man himself. On another occasion, he hunted down a notorious bandit to his home village, killed him, and rode away with the body. The bandit’s head went on display on Nicholson’s desk, a reminder of the consequences for anyone considering defiance of British rules.

From the British point of view, Nicholson was an effective leader and District Commissioner. But he displayed a racism all too common among the Victorian officer class, one which increased tensions in the colonies.

Believing that Europeans were inherently superior to Indians, he ordered that Indians were not to ride alongside whites. When they encountered white men, locals were to dismount and salaam, showing their subservience.

This attitude extended to acts of arbitrary brutality. When faced with the possibility of enemy soldiers passing as civilians, Nicholson had the suspects parade before him, and he decided who was guilty based on his intuition. Men lived and died on his whim.

The Indian Mutiny

The peak of Nicholson’s behavior, for better and for worse, came during the Indian Mutiny of 1857, referred to by some Indian historians as the First Indian War of Independence.

This revolt, triggered by the British mistreatment of native soldiers, featured bitter fighting and terrible acts of brutality on both sides, and eventually led to a British victory. It was a victory in which Nicholson played a key role.

Nicholson led a mobile column in the war, tasked with putting down rebellion wherever it appeared in the Punjab. He pushed his men hard, sometimes making them march through the fearful heat of July days.

Though he had the advantage of traveling by horse, he pushed himself hard too, staying out in the blazing sunshine while his men rested, then riding straight into battle at the end of a march.

Nicholson’s effectiveness came as much from intelligence gathering and cunning as it did from brute force. One evening, he learned from his contacts that Indian cooks were planning on poisoning a group of British officers.

When confronted, the cooks refused to eat the poisoned soup. Nicholson force fed it to a monkey, which promptly died. Having proved the accuracy of his intelligence, Nicholson had the cooks hanged without trial.

The climax of Nicholson’s career came during the Siege of Delhi in September 1857. His flying column joined the British forces besieging the city, and when the time came for the final assault, he commanded it.

He ordered three charges against the Indians holding the Burn Bastion, and was shot leading the third of those charges.

The wound proved fatal. While British troops looted the city and punished the rebels, Nicholson lay dying. He passed away nine days after the assault, on 23 September 1857. He was only 35.

Nicholson’s Legacy

Nicholson’s death did nothing to lessen his reputation. He became a popular figure in British stories of events in India, both real and fictional, and was a hero to those who believed in the colonial cause.

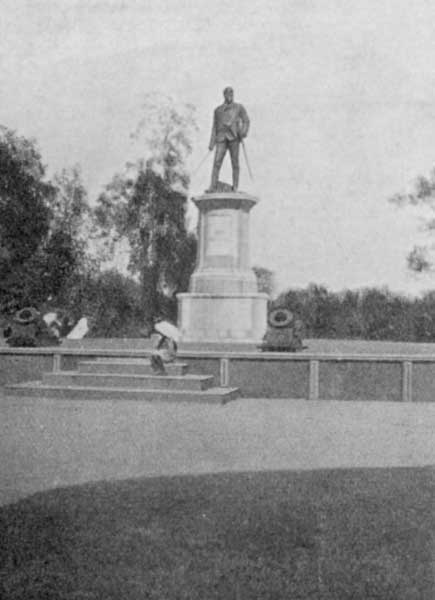

Monuments were erected to him near Taxila and in Delhi. The latter was removed following Indian independence and taken to his former school in County Tyrone. Other memorials were built in Lisburn Cathedral and later in the town’s market square.

Read another story from us: “Stoned” Soldier Started Mutiny in India to End British Rule

The most remarkable tribute to Nicholson was not built of stone but of faith. A cult sprang up around the figure of Nicholson in what is now northwest Pakistan.

There, a small group of Muslims honored the man they called Nikal Seyn as a saint, a figure who brought harsh justice to protect the poor. The Nikal Seynis lived on long after Nicholson’s death, with the last member of the cult dying in 2004.

It was a strange tribute to a remarkable and terrible man.