The Romans were fervent followers of chariot racing. While the movie Ben Hur provides us with a modern interpretation of the sport, the actual events in ancient times were even more exciting, dangerous, and deadly.

Throughout the Roman Empire, from Jerusalem to Rome, people gathered to watch the racers compete.

The Circus Maximus in Rome was the largest arena in the empire. Historians believe that it could hold 250,000 people or a quarter of the entire population of Rome.

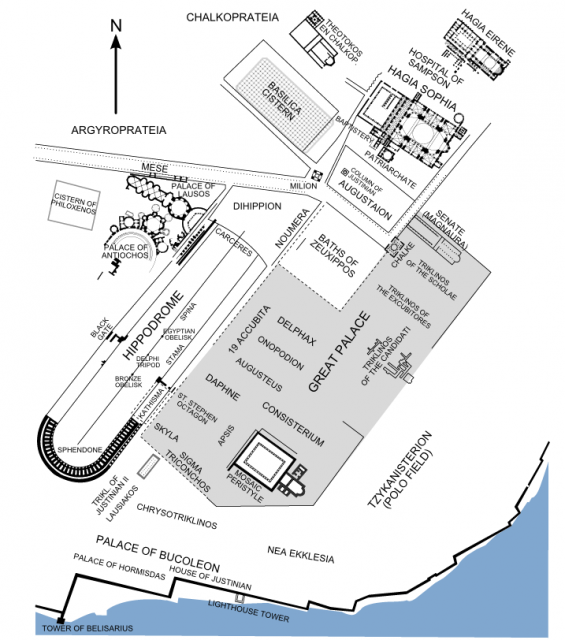

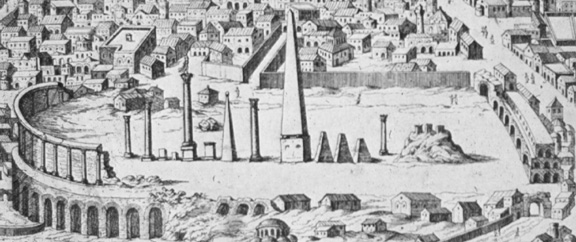

When Rome began to descend in importance, Constantinople began to rise. They built the Hippodrome racetrack. Expert opinions on capacity range from 30,000 to 100,00 people.

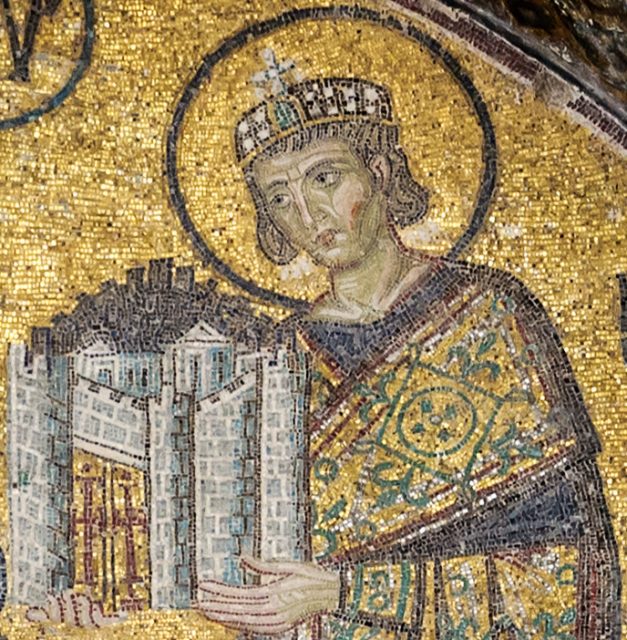

Constantine the Great was the first Roman emperor to convert to Christianity. He also became very interested in chariot races. He had the Hippodrome remodeled to make it one of the most prominent buildings in the city.

It was one of four buildings to frame the city’s central square along with the Senate, imperial palace, and Christian cathedral.

People arrived in droves for the races. Some even slept in the stands to save their seats. In Constantinople, there were two teams: the Blues and the Greens.

Charioteers were idolized by fans numbering in the tens of thousands. Each charioteer piloted a chariot drawn by four horses known as a quadriga.

They raced around an oval track which was about 150 feet (almost 46 meters) wide. They frequently traveled at speeds that were not safe.

Laps were taken around the spina (spine) in the center of the track. The spina was decorated with spoils captured in war.

Maneuvering around the sharp turns at the ends of the spina was often the cause of crashes and injuries. The horses had to be slowed to make the turn, but they still were moving at 20 miles (32 kilometers) per hour.

The charioteers were the professional athletes of their time. They were admired for their skill and their bravery. One charioteer could have 10,000 fans.

One of the best-known charioteers was Porphyrius. He began racing in the provinces and worked his way up to race in the Hippodrome. Accounts describe him as good looking and gifted with amazing athletic abilities.

The Hippodrome races were tightly linked to politics. Leaders were constantly trying to use the race to their own advantage.

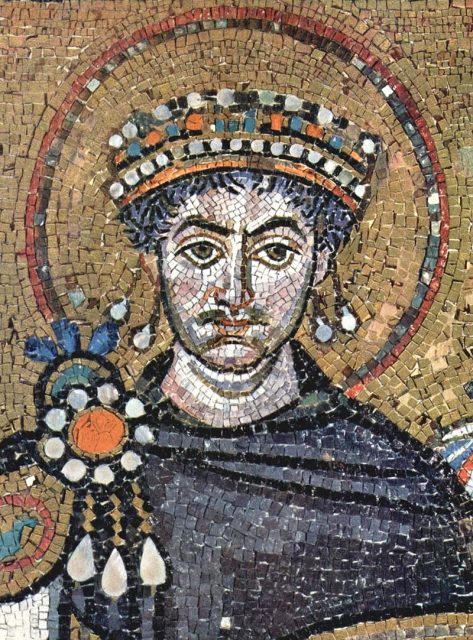

In AD 532, the tension between the Greens and the Blues was at its highest point. At the same time, the population was upset with Emperor Justinian after he raised taxes to pay for his recent military victories.

After fighting commenced between the groups of fans in the Hippodrome, Justinian had seven members of each side executed in a show of strength designed to restore order.

However, one person from each group survived the execution. The crowd immediately rushed the two men to a church where they were given sanctuary.

Believing that the men had been spared by an act of God, the crowds turned on Justinian and began rioting and looting.

Justinian first thought to flee, but his wife, the empress Theodora, convinced him to stay, saying that she preferred death to running away. So Justinian sent out his troops who slaughtered 30,000 men in the Hippodrome.

This occured at the height of popularity for the chariot races. Within a hundred years, the people would be distracted by wars against the Persian Sasanids and then the Arab Muslims.

After that, the rulers in Constantinople would lack the resources to fund the extravagant races.

Read another story from us: Decline of an Empire: The Fourth Crusade’s Sacking of Constantinople

Today, what is left of the Hippodrome is still in Istanbul. The outline of the track is still visible.

But the place of so much violence is now a peaceful park with little to remind visitors of the rich history that occurred there.