Amid the destruction of war, it is easy to forget those who save lives rather than taking them. The work of wartime medics is vital in saving lives both on and off the battlefield. These eight are just a few of military history’s amazing lifesavers.

Mary Seacole

Like the more famous Florence Nightingale, Mary Seacole was a volunteer who saved lives and offered comfort to British soldiers in the Crimean War of the 1850s.

Originally from Jamaica, she was in London when word spread of the terrible hardship troops were undergoing in the war. Unable to gain official support, she traveled to the Crimea under her own steam and set up the British Hotel, offering comfort and medical services to British forces.

As a black woman, Mary overcame extreme prejudice to save lives. She was largely forgotten by historians until her story was revived in the late 20th century.

Mary Edwards Walker

Even without her service in the war, Dr. Mary Edwards Walker would have been worthy of note. The only woman in her class at medical school, she graduated in 1855, despite prejudice against female doctors. When the American Civil War broke out, she was not allowed to enlist to serve in the Union army. Instead, she traveled with them as a volunteer.

She was still not permitted to work as a doctor. Walker worked her way up from nurse to field surgeon’s assistant before being granted a commission in 1863. She was captured by the Confederates while treating one of their wounded. She was accused of being a spy and became a prisoner of war; an accusation that could have gotten her killed.

In 1865, she became the only woman to receive the Congressional Medal of Honour for her work at the First Battle of Bull Run. She went on to campaign for women’s rights.

Captain Harold Delf Gillies

A New Zealand surgeon Gillies was working in London as an ear, nose and throat specialist at the start of the First World War. He volunteered with the Red Cross in France and Belgium, where he saw the horrors of the war.

Gillies became a passionate advocate for reconstructive surgery. Enormous numbers of soldiers sustained head wounds leaving many disfigured for life. He persuaded the British army to set up a reconstructive surgery unit in January 1916, under his leadership.

His team transformed the lives of thousands of men, as well as the techniques of reconstructive surgery. Without textbooks to guide them, they developed procedures to rebuild bone, skin, and cartilage. New challenges in anesthetics were overcome.

Calm, encouraging and cheerful, Gillies helped men to believe they could survive what they had undergone. By the end of the war, his unit had expanded to hundreds of beds. Doctors were coming from around the world to learn from him.

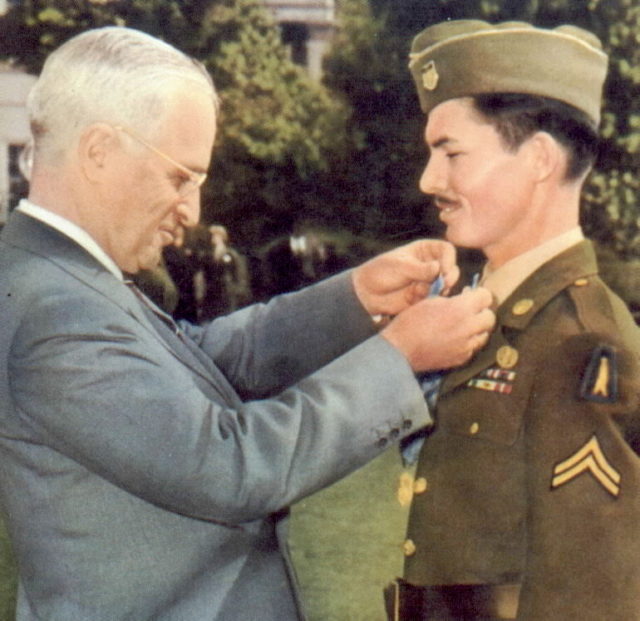

Desmond Doss

Private Desmond Doss was the first conscientious objector to receive the Medal of Honor. Joining the American army in the Second World War, he refused to kill but wanted to serve his country. Other soldiers resented him, and his superiors tried to expel him from the military, but Doss endured.

He proved his courage in battle at Guam, Leyte, and Okinawa. At Okinawa, he attended other soldiers for five hours after being wounded by a grenade and then a sniper.

Robert Bush

Also at Okinawa was the 18-year-old Robert Bush. Finding a casualty with a gaping chest wound, Bush knew the soldier needed an immediate infusion of blood plasma to survive. He inserted the tube, held up the blood bag, and began the process.

Japanese soldiers then charged at them. Drawing his pistol, Bush opened fire while still holding up the blood bag. When the gun ran out, he picked up a rifle.

Hit by shrapnel from three hand grenades, one of which hit him in the eyes; Bush kept fighting to defend his patient.

Geneviève de Galard

In 1954, at Dien Bien Phu, Galard, a French medevac nurse was stranded with troops when her plane was damaged. It was one of the greatest disasters of the Indochina War when Vietnamese forces surrounded the French army.

She helped with surgery, retrieved the injured, and ran a 40-bed ward for the severely wounded. After the French had given up on any chance of winning, Galard worked for 17 more days, until she and the rest of the medical staff were evacuated.

Gary Beikirch

On April 1, 1970, an American camp in Vietnam came under fire from the Vietnamese. Sergeant Gary Beikirch, a Green Beret medic, rushed across the battlefield to retrieve the injured. He was hit in the back by shrapnel which partly paralyzed him.

Rather than being removed from the scene Beikirch called over his assistants. With the battle still raging, they carried him around on a stretcher so he could tend to the injured. He was shot twice – once in the side and once in the stomach – but survived the battle and eventually recovered from his paralysis.

Sally Clarke

Beikirch is not the only medic to continue treating people with shrapnel buried in their back.

In 2009, Lance Corporal Sally Clarke was serving with the British Army in Afghanistan’s infamous Helmand province. When the Taliban hit her patrol with a rocket-propelled grenade Clarke, and seven other soldiers were injured. The only medic in the group, Clarke rushed between patients, binding their wounds, despite a piece of shrapnel lodged in her own back. She refused to be evacuated while the patrol needed her skills. For her actions, she received the Queen’s Commendation for Bravery.

Sources:

Taylor Downing (2014), Secret Warriors: Key Scientists, Code-breakers, and Propagandists of the Great War.