He had lived in Israel for three years, where he carried a rifle for an oil company in the Negev Desert. He’d been a cowboy on a Kibbutz, a fisherman in the Mediterranean Sea.

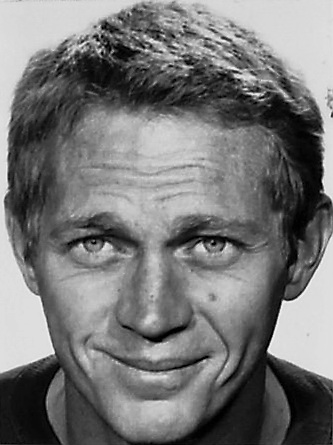

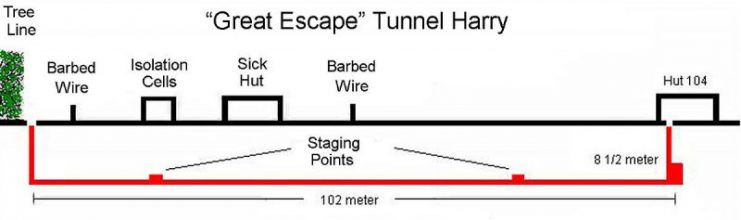

The real “Great Escape” from Stalag Luft III happened 75 years ago and was immortalized in the classic movie The Great Escape 19 years later. It made an international star of Steve McQueen, reunited with director John Sturges who had given him roles in Never So Few (1959) and The Magnificent Seven (1960). But could another actor have been launched to super-stardom instead of or together with McQueen?

Everyone knows that the famous jump over the wire that McQueen makes as Hilts racing for the Swiss border was actually performed by dirt-biker Bud Ekins. Sixteen years after the legendary stunt, Ekins was working on the Disney film Escape to Witch Mountain with an actor he had met on The Great Escape.

Ekins and his actor buddy were, according to the actor, “s***-faced” one night and Ekins quipped to his drinking companion “Ya know, if they left in all the scenes you had in that film, you’d be where McQueen, Bronson and Coburn are today.”

Ekins said those words to Lawrence Montaigne, who had played Haynes in The Great Escape. Haynes was one of the two POWs in charge of “diversions,” or distracting the German guards. He was disguised as a German for the tunnel escape, and was famously tricked into speaking English during the escape rehearsals by fellow POW Gordon Jackson.

That foreshadows how Jackson himself is tripped up and uncovered with a “Good Luck” from a Gestapo agent later in the film. You see Haynes later in the Gestapo cells, having also been captured. During the film’s poignant climax he is murdered by machine-gun along with Jackson, Richard Attenborough, and 67 others.

I learned the Bud Ekins story from Montaigne himself who kindly agreed to an e-mail interview with me in 1999. In it, he elaborated about his time on The Great Escape movie set in Germany back in 1963.

Montaigne: “One week into the shooting, Steve McQueen decided he didn’t like his role in the script and we shut down for a week while a writer came in from California to rectify his grievance. At that time, I had signed a contract for only five weeks since in the original script I didn’t escape. But when the revisions came down, much to my surprise, I got out of the camp as a German soldier (probably because I speak the language) and eventually I ran nineteen weeks on the shoot.”

Montaigne did indeed speak German as well as Italian and French and had lived in Europe for some years as a jobbing actor, stuntman, and voice-over artist dubbing Italian films into English.

He had also been a U.S. Marine, so he was comfortable with military roles. He had lived in Israel for three years, where he carried a rifle for an oil company in the Negev Desert. He’d been a cowboy on a Kibbutz, a fisherman in the Mediterranean Sea, and set up his own photography business in Rome.

From Rome he freelanced as a photojournalist, traveling all over the world to cover stories. Being part Hungarian, he claimed a “gypsy lust” for travel. As a photographer he had worked in India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and such exotic cities as Bangkok, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Kuala Lumpur.

Added to all this, in 1963 he was given a role in MGM’s new POW epic The Great Escape, based on the book by Paul Brickhill.

So what missing footage was Ekins referring to, that did not make the final product we all love so much to this day? The first cut scene occurred early in the film just after the POWs’ arrival at the new camp. John Leyton needs Montaigne and James Coburn to stage a fight “knuckles” over a battledress jacket to create a diversion so Bronson can slip into a group of Soviet workers and escape.

Robert Relyea, the film’s associate producer, directed this particular scene. Montaigne was supposed to sneak through the compound, searching for a way to get out. Two stuntmen portraying prisoners are standing by a hut, one with a walking cane.

Montaigne: “As I approach, I nod to the two stuntmen, one hands the other end of the cane to the other. I take a dramatic running leap, jump up onto the cane and they catapult me into the air, up onto the roof.”

Montaigne recalled that they did about 20 takes of this action, but despite their combined efforts, due to the 18 inch overhang of the hut’s roof they never quite achieved the stunt in a fluid motion and the sequence was abandoned. Later, you do see Montaigne jump from the roof of the hut into a pile of branches on the back of a truck that was about to leave the compound, but not the spectacular leap upward.

The second cut scene comes after Montaigne’s break out with the other prisoners.

Montaigne: “I am being pursued and I take refuge under a bridge. I take off my helmet and begin to burn my papers in order not to be captured as a spy. Then, a couple of German soldiers appear at the far end of the bridge.”

Montaigne makes a dash for freedom, but a German (Roy Jenson, the same stuntman with the cane earlier) takes a flying leap from the bridge onto him! Montaigne recalled,

Just as he is about to land on me, I turn and throw a punch and he collapses to the ground as the other soldiers capture me. Okay, so you’ve got the picture and again it is a stunt that takes perfect timing because if I don’t throw the punch at just the right moment with Roy airborne, the whole stunt goes down the hopper. Now, you’ve got to know that Roy is wearing a vest under his uniform and a wire is attached to the vest and the other end of the wire is tied off to the bumper of a car. When Roy reaches the end of that wire when he is airborne, he drops like a sack of manure. Theoretically, this stunt should have looked spectacular and we did it a number of times until Roy could barely walk with all the trauma to his person.

Of course, that cool stunt didn’t make the final cut either. What a pity, as it sounds far more exciting than the capture of Nigel Stock as Cavendish, who is simply taken while a passenger in a lorry.

The final important scene Montaigne filmed was in the Gestapo prison just after Nigel Stock explains why he had to dye his jacket and had lost his insignia. He joins Montaigne in the cells.

Montaigne: “Now, that scene in the cell was a much longer scene in which I break down and cry because I don’t know what is going to happen to us and I am scared. It was quite a good scene and I was really sorry that it never made the final cut.”

After a career of 40 years Lawrence Montaigne passed away in 2017 at 86 years old. He had memorable roles in the Star Trek series as a Vulcan, the war film Tobruk with Rock Hudson and George Peppard, and many other small roles.

Read another story from us: Paul Woodadge: Filming the Battlefields of WWII

Who knows what would have happened had his additional scenes in The Great Escape not been left on the cutting room floor? But as he said to me: “So you see, I really had quite an active role in the film but it never made it to the screen. At first I was greatly disappointed but when one considers that the first cut of the film ran some eight hours, it is easy to see that something had to go. C’est la vie.

“Good God, Paul, you’ve got me talking about things that happened nearly forty years ago! I don’t have any bad feelings about not becoming a star. I can tell you one thing; I had a ball working on The Great Escape and all the other films I did. I wouldn’t trade it in for all the money in the world.”