An army marches on its stomach, and while a Navy sails on the sea, its sailors still need feeding. In the 1790s and early 1800s, the Royal Navy had to provide rations for over 100,000 men, with no refrigeration, modern preservatives, or packaging. This proved to be a difficult task, but one which the Victualling Board tackled head on, providing their sailors with a hearty, if not diverse diet.

To better understand how the sailing men ate at the time, let us take a single ship as a case study.

In 1800 HMS Arethusa and her 280 men were sailing out of Portsmouth and had full access to the Admiralty’s stores. As she was so close to home, her crew would likely have eaten by-the-book rations, with very little being substituted due to scarcity.

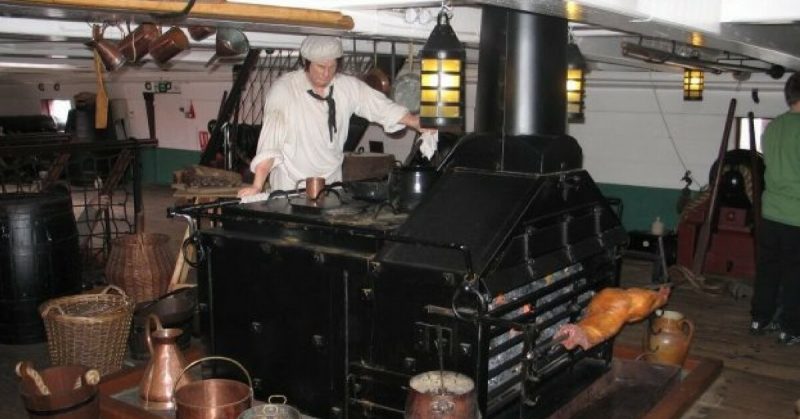

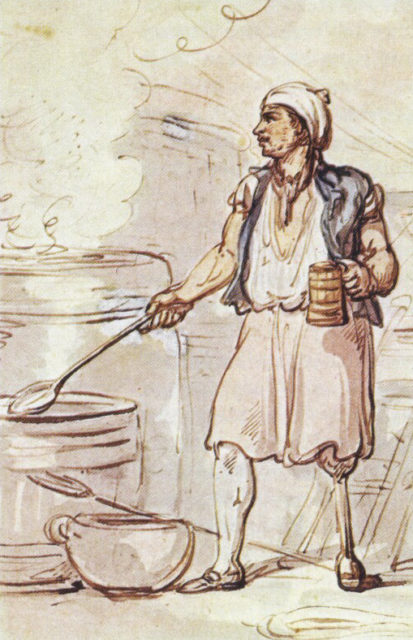

Of the 280 men, each of the ordinary sailors were formed into messes. This was the necessary administrative grouping of sailors, but functionally, it was with whom they ate. Each week a man from each mess would be made the mess cook. He would assist the ship’s cook, collect and prepare his mess’s rations. His day started early, to produce breakfast.

Each morning, the stoves would be warmed up. The breakfast ration, usually oatmeal, would have been soaking the night before, so it only required warming up. At 8 bells on the morning watch (8 AM) the oatmeal was dished out.

It was often sweetened with molasses, sugar, honey, or whatever else might be on board. Oatmeal was never unpopular, but the men preferred eggs or meat, if available. Oatmeal or whatever else, the men had 45 minutes to eat and then return to their working duties.

Immediately after breakfast, preparations for dinner, the noon meal, began. This usually consisted of meat, which brought its own problems. The only reliable method to preserve meat was heavily salting it. This allowed the meat rations to last for months at a time, but it was inedible straight out of the barrel.

Each man was allocated one pound of pork on Sunday, and Thursday; and two pounds of beef on Tuesday and Saturday. Each time this was to be served, though, it had to be carefully prepared.

The meat was soaked in fresh water for hours, with the water being frequently changed. This got it to the point of being edible, but still somewhat salty. The meat would then be boiled, or if a ship’s cook was kind, lightly fried or grilled. It could also be made into a lobscouse, or stew, cooked with potatoes, onions, and anything else the crew could scrounge.

It was served with a pound of ship’s biscuit. Hard, ¼ pound disks of flour, baked 2 or 3 times until all moisture was completely gone. The men would soak these, usually breaking them into their stews, or letting them soak up the juices from their meat ration.

The meal would also be served with a tot (alcohol ration). On Arethusa, the tot was most likely beer, as being so close to home it was easily acquired. Each man was allowed a gallon per day, keeping them happy and full, if a little drunk!

Dinner was expected to last around 1.5 hours, enough time for the men to feel full, and ready to return to their arduous work.

Next came supper; usually a pudding, made of flour, suet or butter, and raisins. The men could add whatever fruit they may have bought in port, or any meat left over from their rations.

The puddings were shaped into balls and then placed in a linen or cotton bag to be boiled. This produced a soft, filling, and often sweet meal, which did not take much effort to make.

Like breakfast, supper would last 45 minutes, after which the men might return to work, or perhaps dance and skylark on the deck.

In all, Royal Navy sailors consumed an average of around 5,000 calories a day, well above today’s suggested average. At the time, their workload required such a high intake. Men were expected to work 12 hour days, including being on watch duty in the middle of the night.

An average day would consist of climbing the rigging to adjust sails, moving vast and heavy equipment around the deck, and long hours of gun drills. More than enough to burn all 5,000 calories.

What is more, the men had no reliable protection against the weather, burning many of the calories just to keep warm!

This diet lasted for most of the 19th century and did not drastically change until steam powered refrigeration allowed for more variety in meals onboard.