Rear-Admiral Horatio Nelson, the rising star of the British Royal Navy, had been pursuing the fleet of the French Republic around the Mediterranean for the last two months. The French objective was to land an invasion force on the Egyptian coast, and this had been achieved. The French land army, led by Napoleon himself, had taken the city of Alexandria by force and then proceeded inland. The French fleet, under the command of Admiral d’Aigalliers, anchored in the wide, sheltered coastal waters of Abuqir Bay, near Alexandria.

It was 1798. In the five preceding years, numerous attacks by an alliance of European powers had failed to defeat revolutionary France. The coalition of states which had opposed the new Republic had collapsed, and the only country left still at open war with France was Great Britain. At this time, Britain’s navy was her most powerful weapon, and the French were working hard to build their sea-going strength to a level where they could challenge the Royal Navy for control of the waves.

The key to the continued success of British war effort was the vast wealth generated by her colonies in the Indian subcontinent. Napoleon’s plan at the time was to secure a power base in Egypt, from where the flow of communications and money between Britain and India could be disrupted.

Nelson, at last, caught up with his enemy on the 1st of August, 1798. The only thing on his mind was the prize, and he immediately gave the order to prepare the attack.

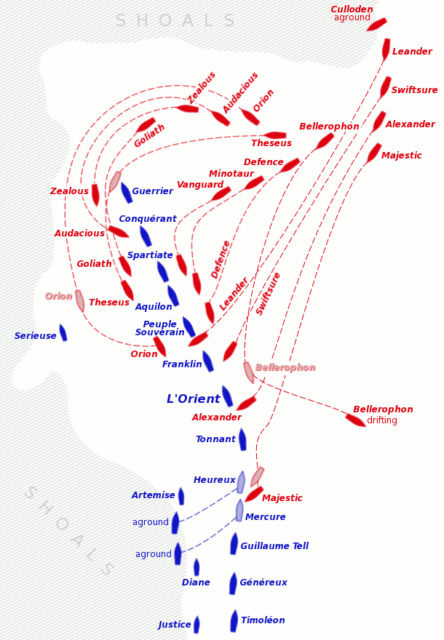

Admiral d’Aigalliers had deployed his fleet in a line of battle stretching the length of the bay. There had been some disagreement among the captains about what course of action they should take, but the Admiral’s opinion had prevailed. When Nelson found them they were deployed like an entrenched army, with the great 120-gun flagship Orient in the middle of the line.

The two fleets first spotted one another at two in the afternoon, but manoeuvring a fleet takes time, and the battle would not be joined for another four hours. The French Admiral called his captains to a council of war on the flagship. Nelson gave the orders to prepare his ships for night-fighting, fitting each with four lights on the mizzen-mast to reduce the risk of his own ships firing on one another in the confusion of battle.

Nelson and d’Aigalliers’ forces were fairly evenly matched. Both had thirteen ships of the line at their command, plus a handful of smaller vessels, but Nelson had the advantage of numbers when it came to men. The French Admiral had been forced to send foraging parties ashore under heavy guard, as Napoleon had stripped the boats of most of their food and water when he had disembarked with his army.

When Nelson’s fleet had been sighted, d’Aigalliers had given orders that the foragers and their guards should return with all haste, but by the time the battle began most of these men had not managed to rejoin the fleet.

Nelson’s fleet attacked in two lines. The first, with Nelson’s flagship fourth in line, attacked the seaward side of the French vanguard. The second line crossed right in front of the nose of the leading French ship, then swung to the left. In this way, the first four French ships were caught in a devastating crossfire.

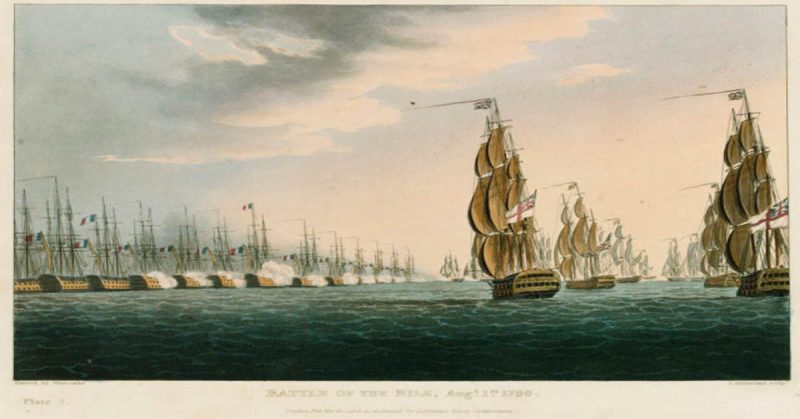

The first shots were fired at six o’clock. It had taken Nelson two months to find them, and four hours to bring his ships to bear, but by nine o’clock that evening the French fleet’s vanguard was in pieces. Two ships suffered incredible damage and loss of life before at last surrendering to boarding parties.

One had drifted near the land where it was sinking. A fourth had given determined resistance, but the captain could not challenge the weight of fire that was laid on his vessel. His ship’s masts were gone, and he was badly wounded when at last he ordered his ship’s surrender.

The British fleet was now approaching the centre of the French line, where the heaviest guns were grouped around the flagship. As they approached, Nelson’s ship took one raking broadside which killed more than a hundred men. The Admiral himself was wounded, but the ship which had landed the blow was quickly subdued by the combined fire of the British advance.

The lead British ship was a three-masted 74-gunner named Bellerophon. She had gone forward from the main battle and engaged the French flagship, and for hours, they had duelled at close range. The French Admiral d’Aigalliers was killed on board, hit in the belly by a speeding cannonball, but his ship fought on. Eventually, the Bellerophon could fight no longer, so the wounded captain ordered the anchor cut and she drifted away.

On board the French flagship Orient, a fire had broken out below decks. The ship was heavily damaged but still far from surrender, and the crew scrambled to quench the flames. Five British ships, including Nelson’s flagship, were now in the range of the Orient. Broadside after broadside rocked the huge vessel, and the flames began to spread.

The Orient became a towering inferno under the bright moon, and the British began to withdraw with gun ports closed. The sparks and flames licked high into the night, roaring and crackling. All around the surface of the water was choked with the bodies of the dead, with wooden debris, men swimming and little boats full of people rowing desperately away from the blazing ship.

The sudden explosion of the Orient‘s powder magazine was deafening, and the shockwave rocked the attacking vessels and knocked their crews flat. When the British sailors recovered and gazed across the water they saw only a few pieces of burning shrapnel. The Orient was no more.

The fighting continued right through the night. During the hours of darkness, fresh British ships arrived to reinforce the attack. After the destruction of the Orient the remaining French ships were thrown into chaos, and one by one they were surrendered or destroyed.

By late morning of the next day, it was all over. Two ships of the line and two small frigates managed to escape the destruction, led away by Villeneuve, the French second in command. The British had captured nine ships and destroyed four, and they had taken almost a thousand prisoners. It was a resounding victory for Nelson, and his fame, his wealth and his reputation were secured.