Imagine a Monk

What do you see? Do you imagine the traditional Zen Buddhist monks of Japan, shaven-headed men in bright robes sitting in meditation in the shade, amidst a rain of cherry blossoms? Perhaps you think of Shaolin monks demonstrating traditional kung fu techniques in their famous temple on Mount Song, or of the smiling face of the Tibetan Buddhist spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama, preaching compassion and peace to audiences across the world.

These are all fairly accurate, if somewhat stereotypical, depictions of the Buddhist monks of today, but many of the monks of Japan’s past were very different characters. From the mid 10th century to the latter 16th century, the monks of Japan were willing to don armor, pick up arms, and meet their religious and political threats in the field of combat.

It is Always Politics (10th Century)

In the 10th Century, multiple temples began a trend of militarization. The temples that stand out are the Tendai Buddhist temples of Enryakuji and Onjoji/Miidera located on Mt. Hiei near Kyoto and the Kofukuji temple in Nara. In all times, there are differences of opinion, so it should be no surprise to know that there were different factions among the temples.

The Ennin faction dominated Enryakuji Temple and the Enchin faction ruled Miidera. In 970 C.E., the temple of Enryakuji began developing and maintaining a force of warrior monks; it would be a first step toward complications.

The temples coexisted with relative peace until the faction of Miidera tried to encroach on Enryakuji’s territory. In 998, a monk named Yokei was named as abbot of the Enryaku-ji Temple. Yokei was not a sound fit for the job of abbot in Enryakuji, as he was from a rival faction and temple.

The Enryakuji Temple did not belong to Yokei’s faction, so they were understandably displeased. To show their discontent with their new abbot, roughly two hundred monks of Enryakuji launched a violent protest in the city of Kyoto. Taking the hint, Yokei resigned from his position.

Unfortunately, Yokei and his faction did not take the Enryakuji Temple’s stubbornness lightly. The monks of Miidera continued to pressure the Enryakuji Temple to accept Yokei as the abbot, but his leadership was continually rejected. In 993, after twelve years of arguing about Yokei, Miidera had finally had enough of Enryakuji’s stubbornness and launched an attack.

Once the pro-Yokei monks from Miidera forced their way inside their rivals’ complex, they burned the main temple complex to the ground. In response, the monks of Enryakuji went on their own rampage, burning forty shrines of the Miidera Temple’s faction. Having vented their frustrations on their rival’s shrines, perhaps the rivalry could have dispersed peacefully. Unfortunately, the feud would only deepen further.

Pure Escalation (11th and 12th Centuries)

The later events of 1039 prove yet again that history repeats itself and that events of the past can return with a fury. In 1039, the “powers that be” in Japan tried, once more, to place a monk from Miidera as the new abbot of the Enyrakuji Temple. Predictably, this action instantly ignited fierce opposition. As in 993, Enryakuji monks prepared to protest. This time, however, many more than the original two hundred Enryakuji monks armed themselves for their cause. In fact, around three thousand monks left Enryakuji Temple, descended on Kyoto, fought through a guard of samurai and successfully demanded that the Daimyo (feudal warlord) of the powerful Fujiwara clan cancel the decision. The Enryakuji Temple, nevertheless, was apparently still bitter, for the Miidera Temple was invaded by rival warrior monks in 1074, 1081, 1121 and 1141, their shrines left to crumble and smolder.

The temples, though they had a tense coexistence, could sometimes manage to work together against a common foe. The temples of Enryakuji and Miidera actually combined their forces in 1081 and 1117 to attack a third temple, the Kofukuji Temple in Nara. Kofukuji and Miidera lent their warrior monks to the Minamoto clan during the Gempei Civil War from 1180 to 1185.

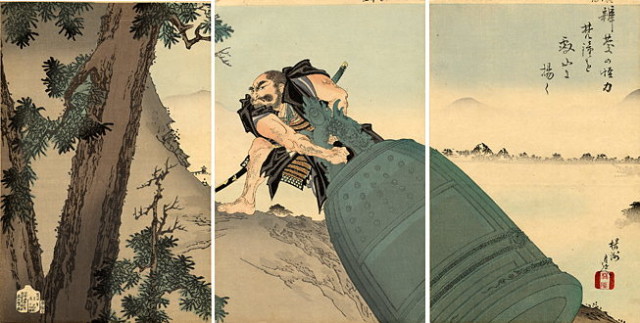

Of all the warrior monks, one stood out to become a legend. His name was Benkei. He was a member of the Enryakuji Temple who set up camp at an abandoned shrine after being exiled. His legendary story reinforced the feud between Enryakuji and Miidera, as he supposedly stole a bell from Miidera to adorn the abandoned shrine he called his home. When Benkei realized that the ring of the bell was not pleasing, he returned the bell to the Miidera Temple by means of a powerful kick, sending the bell tumbling down Mt. Hiei to its former home. At some point, Benkei dueled the warlord Yoshitsune Minamoto, and after being bested, joined the warlord’s retinue. Benkei followed Minamoto until they both met their deaths in the battle of Koromogawa in 1189.

The Lotus Sect, Ikko-Ikki and Warlords (15th and 16th Centuries)

In 1488 a Buddhist group called the Ikko-Ikki took root in the region of Kaga and conquered surrounding provinces. Another new Buddhist force arrived in 1500 in Kyoto. Naming themselves the White Lotus, they constructed twenty-one fortified temples. They helped the Shogun’s forces in Kyoto repel an invasion from the Ikko-ikki in 1528, and went on the offensive against the same group six years later. The Lotus Sect only lost their power and influence when the warrior monks of Enryakuji Temple attacked Kyoto and destroyed all twenty-one of the sect’s fortified temples.

The 16th century was both the golden age, and the downfall, of the warrior monks. The main cause of the decline of the warrior monks was the warlord, Oda Nobunaga. In 1570, Oda handed the Enryakuji Temple a defeat unlike anything they had ever experienced—he encircled their compound and burned it to the ground. Around twenty thousand monks died that day.

The warrior monks of the Ikko-Ikki brought the wrath of Nobunaga Oda upon themselves when they killed the warlord’s brother. In response, Oda waged war on the Nagashima Ikko-Ikki from 1571 to 1574. Oda herded his warrior monk opponents onto one island fortress—Nagashima Castle. The castle kept the defenders in as much as it kept the attackers out. Therefore, the Ikko-ikki had nowhere to run when Nobunaga Oda set bundles of flammable materials around the castle walls and set fire to the fortress, with the Ikko-ikki still inside. With the fall of Nagashima Castle, around twenty thousand more lives were lost to Nobunaga’s flames. In 1580, Nobunaga subdued another Ikko-Ikki force in the region of Ishiya Hanganji. This time, he let his foe surrender. Nobunaga, in this case, should be given credit for style, as he reportedly made the Ikko-Ikki leader sign the peace with blood and the Ikko-ikki compound was burnt for good measure. With the Enryakuji Temple burned, and the Ikko-ikki pacified, the warrior monks of Japan would never be the same.

Imagine a Monk, Again.

The idea of the Japanese monk as a humble person doing sitting meditation in the shade of blossom trees is still true of for the monks from the tenth to sixteenth centuries. But savor the peaceful image, for those peaceful medieval monks might explode into war at the slightest annoyance from their rivals.

By C. Keith Hansley—Read all of his articles at http://historianhut.blogspot.com

For more on Japanese warrior monks, read Stephen Turnbull’s Japanese Warrior Monks AD 949-1603, which was the source for much of this article.