War History online proudly presents this Guest Piece from Samuel B. Parker.

Desperate times call for desperate measures.

But just how desperate can measures be before they’re considered preposterous, absurd, or even unthinkable? Some measures are so desperate that they seem positively destined to end in disaster and ignominy.

The men behind these seemingly suicidal maneuvers, however, did not like to be told the odds.

3. Chamberlain’s Charge, Battle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg was not only the single deadliest military confrontation of the American Civil War, it also ranks among the bloodiest armed engagements in United States history. All told, some 50,000 soldiers were killed, wounded, captured, or went missing in the course of the three days of fighting in early July of 1863. Over 20,000 men who participated in the campaign were never to return home.

The Battle of Gettysburg was crucial for both factions of the War Between the States. The Union victory marked a major turning point in the ongoing civil conflict, and Confederate forces never recovered from the devastating and decisive defeat; General Robert E. Lee and the Confederate troops did not win a major battle after the Battle of Gettysburg, nor did they manage a successful offensive excursion on the heels of the Union’s greatest victory.

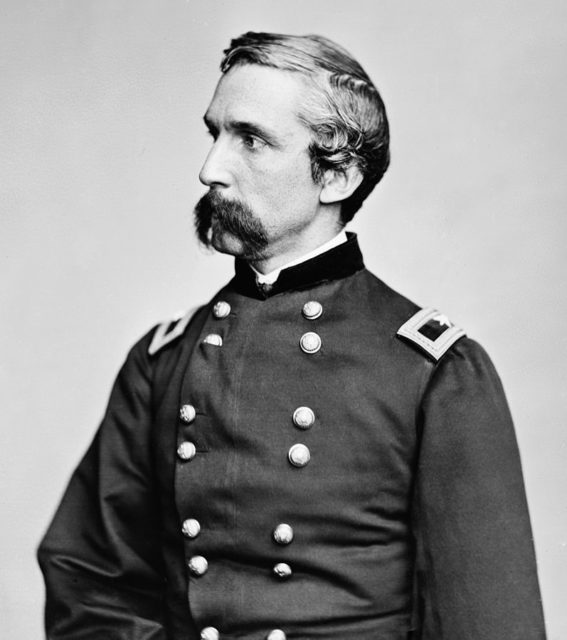

President Abraham Lincoln, General Ulysses S. Grant, and the Union owed much of this to General (then Colonel) Joshua Lawerence Chamberlain.

Before volunteering to serve in the Union army at the outset of the Civil War, Chamberlain was a college professor at Bowdoin College in Maine. Originally entering the service as a Lieutenant Colonel of the 20th Maine Regiment, he achieved the rank of Colonel subsequent to the promotion of his superior officer, Adelbert Ames.

During the Battle of Gettysburg, the 20th Maine under the command of Colonel Chamberlain was ordered to assist in the defense of a highly strategic position known as Little Round Top; Colonel Chamberlain’s regiment was stationed at the very end of the Union line, and he was instructed to hold the hill at all costs. Little Round Top was situated at the far left side of the Union defense at Gettysburg, and thus forfeiting the position would potentially result in a complete and catastrophic Union defeat. Colonel Chamberlain and his men were manning the most important position in the most influential battle of America’s most consequential war.

They more than lived up to the challenge.

On July 2nd, 1863, several days into fighting at Gettysburg, Colonel Chamberlain and the 20th Maine were attacked by the numerically superior 15th Alabama Regiment commanded by Colonel William C. Oates. The initial Confederate advance was fierce and proved disastrous for the 20th Maine; after multiple concentrated strikes against the Union column in an attempt to flank the position, Colonel Oate’s 15th Alabama had inflicted heavy casualties and the 20th Maine had nearly doubled back on itself.

With ammo running out and with the Confederate outfit on the verge of victory, Colonel Chamberlain, in a last-ditch attempt to preserve the Union defense, ordered a suicidal charge headlong into enemy fire.

Leading the way, Colonel Chamberlain enjoined his troops to fix bayonets and draw swords. Although easily outnumbered and outgunned, the 20th Maine rushed brazenly down the hill directly into oncoming gunfire, shocking the men of the 15th Alabama and halting the Confederate advance. Chamberlain’s Charge eventually broke the Confederate line and forced the enemy brigade into full retreat.

The actions of Colonel Joshua L. Chamberlain saved the day, allowing the Union to hold its vital position at Little Round Top, which ultimately played a significant role in affording the eventual victory at the Battle of Gettysburg to the Union Army. Colonel Chamberlain’s actions merited a Medal of Honor (he became a recipient in 1893) and allowed the Union to take control of the American Civil War.

2. Defense of Athens, First Greco-Persian War

The First Greco-Persian War is among the most remarkable military upsets of all time, and much of that is due to the sheer nerve, courage, and heroics of the Athenian army under General Militades at the Battle of Marathon.

In 499 B.C., the Persian Empire had subjugated the entirety of the known world and Persian rule had been solidly imposed for over fifty years. As a result, it came as a great surprise when a small revolt broke out among isolated cities located in the Greek province of Ionia. Declaring themselves an autonomous and independent state, a handful of Ionians attempted to come out from under the heavy hand of the Persian authorities. Athens lent its support to the rogue Anatolian cities, and though the Ionian rebellion was easily and quickly repressed (with austere consequences for those who had taken part), Athens’ participation in the uprising served as a convincing pretext for a total Persian invasion of Greece.

Vowing to overthrow and destroy Athens for its encouragement of the Ionian insurrection, King Darius the First of Persia amassed the most immense invasion force in ancient history. The First Greco-Persian War began nearly a decade after Darius first began plotting the annexation of Greece, as the Persian army of over a million strong crossed the Dardanelles in 492 B.C.

After attaining submission from all Greek territories with the exceptions of Athens and Sparta, Darius turned his attention to these defiant regions. Marching on Athens, the Persian armed forces met heavy resistance in the Greek reinforced countryside just outside the city of Marathon.

The allied Greek forces had assembled before the city walls in an attempt to salvage the war effort and drive the Persians from their homeland. Though vastly outnumbered and facing far superior weapons technology, strategy, and tactics, the Athenians lead by General Militades were determined not to yield the city without a fight.

The Persian onslaught proved overwhelming and unstoppable, and the Greek defense soon began to capitulate under the weight of the most elite, sophisticated, and highly trained military of its day.

Running out of options, Greek General Miltiades elected to try for a head-on charge, spurring on and marshaling his troops with a simple command: “At them!”

Expecting the seemingly suicidal maneuver to be a feint or a ruse, the Persian line did not prepare for the impact of the frontal assault; the Persian defense folded in surprise and panic after being surrounded and pressured toward the center, and subsequently flanked by the left wing of the Greek infantry, which had previously remained out of sight. Quickly collapsing, the Persians broke formation and the Persian commanders ordered a full retreat.

The Greek victory during the Battle of Marathon marked the turning point of the First Greco-Persian War, as the Persians were subsequently ejected from Greece by the defenders. The actions of General Militades and the Athenian troops brought unity amongst the Greek city-states, ensuring ultimate victory in the Second Greco-Persian War and reshaping the military climate and landscape.

1. Doolittle’s Raid, World War II

By the spring of 1942, the United States had finally parted ways with its longstanding insistence on international neutrality, having entered World War II aligned with the Allied Powers of the United Kingdom, France, and the Soviet Union, among others.

The United States’ decision to join the war effort was influenced by numerous different factors, but the dramatic shift in public opinion, geopolitical policy, and military approach was driven primarily by the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor Naval Base in Oahu, Hawaii on December 7th, 1941. As such, the American people and the American military alike were hungry for revenge.

As of April 1942, the forces of the Japanese Empire had orchestrated and conducted a series of swift and coordinated attacks, seizing key American positions in the Philippines and on Wake Island and Guam before the U.S. Pacific Naval Fleet had even recovered from the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Eyeing imperial conquest, the Japanese Navy was setting the stage for complete domination of the South Pacific.

But the Americans were not to be pushed around, and they responded quickly.

In America’s fast retaliatory offensive against the Japanese mainland, Lieutenant. Colonel James H. Doolittle led a fleet of sixteen American Mitchell B-25 medium-range bombers on a daring raid over Tokyo.

Doolittle served with distinction in World War I and was widely hailed as a highly skilled pilot during the inter-war period. Upon his promotion to Lieutenant Colonel in early 1942, Doolittle promptly volunteered for the top-secret mission in the late stages of the planning process. His request to lead the mission was approved.

The raid targeted factories and warehouses that produced and stored wartime goods and materials, weapons, and planes. Though the attack (which later became known as “Doolittle’s Raid”) did little actual damage, it served to discredit the Japanese government’s claim that the homeland was untouchable and invulnerable, to frighten the Japanese citizenry, and to provide a much-needed boost to American morale. As a result, the raid was and is viewed as a brilliant success.

The catch, however, was that there was no simple plan of escape. Because of the limited range of the B-25 bombers and their inability to land on the USS Hornet aircraft carrier from which they had taken off, the American pilots and crews were forced to crash land in China and escape the Japanese-occupied country on foot. Going into the raid, Lt. Colonel Doolittle and his men knew that they were punching a one-way ticket; they were fully aware that they would be forced to ground their crafts in enemy territory and elude Japanese troops until they could find a way to exit the heavily-garrisoned nation.

Miraculously, of the eighty men who participated in the mission, only three were killed in action and only eight were captured; the remaining sixty-nine combatants managed to slip past the searching Japanese military and across the Chinese border to safety.

Lt. Colonel James Doolittle later received the Medal of Honor for his compelling leadership and heroism, and though World War II was ultimately resolved by use of explosives and incendiaries which drastically dwarfed those dropped by Doolittle and his men, the raid remains one of the most influential and decisive American maneuvers of the Second World War.