War History Online proudly presents this Guest Piece from Manolis Peponas

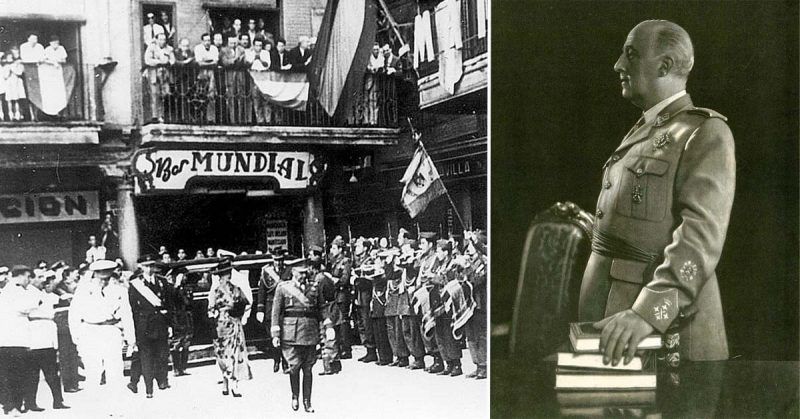

The dictatorship of general Fransisco Franco in Spain was one of the most despotic regimes during World War II. Receiving reliefs by Nazi Germany and fascist Italy, Franco beat the republican forces. In the spring of 1939, he was able to govern Spain as the winner of a bloody civil war which lasted almost three years. Some months after, German troops invaded to Poland and World War II began. Allies believed that a cooperation between Franco and Hitler was predictable and Franco had to “fight” for his political survival.

In ideological sector, however, there were some significant differences between fascist states and Franco’s Spain. First of all, Franco was a conservative general, not a far-right politician like Hitler or Mussolini. His cooperation with Falange was necessary because they had the same enemy: the elements of Spanish Republic. Moreover, Falange, perhaps the most remarkable fascist organization in Spain, was never powerful. When Franco was feeling some pressure from Falangists like Serrano Suner was able to isolate them.

However, the most important thing was that Franco never planed a “fascist revolution”. In fact, he tried to restore the privileges of the traditional class which ruled the country before the 1930s’. Of course, British diplomats were able to recognize all of those differences and knew pretty well that Franco’s regime had not so many similarities with Nazi Germany.

However, the key factor for Franco’s survival was the weak political opposition that he had to face. As S. Grover Rich noted: «There are those who place great faith in the possibility of a peaceful removal of General Franco in favor of a more “popular” government. Popular with whom? No force can come to power without at least the support of the Army, and in view of its present makeup Army blessings would imply approval by landowners and the Church also. The most that realistically can be hoped for is the establishment of a puppet monarchy, the reigns of government remaining in their present hands. Even should something better be obtained, what would come of efforts at land reform, or of attempts to weaken the power of the Army or the Church? The lesson of the Spanish Civil War is clear to those in doulbt» (S. Grover Rich, p. 398).

Those people who confronted Franco were divided into a lot of groups. Organizations associated with the Popular Front, for example, moved in Mexico after the occupation of France by German troops. On the other side, in Portugal and Switzerland, there were monarchists who asked the restoration of Don Juan, the exiled Pretender of the throne. Both of them were weak and it was impossible to antagonize Franco.

Moreover, every government which anticipated Franco knew pretty well that any move to replace Franco with a regime favorable to the Allies would have driven him straight into the Germans’ arms or else precipitated a Wehrmacht invasion of the Iberian Peninsula. Consequently, until the removal of the German threat to Spain with the Liberation of France in 1944, overt cooperation with the Spanish opposition was considered at best irrelevant and at worst perilous.

Only as the war-time strategic factor lost its immediacy could the terms of Britain’s relationship with Spain change. It was then, after the general election of July 1945, specifically to the new Labour government of Clement Attlee and to his Foreign Secretary, Ernest Bevin, that responsibility for Britain’s relations with the Spanish opposition fell for the rest of the decade (Dunthorm, p. 6).

In conclusion, there were a lot of reasons that could explain why Allies never tried to abolish Franco’s regime. The most serious was that, without having an alternative political solution for Spain, every attempt against Franco would be too risky. A German invasion supporting the Spanish dictator was always possible, so before the collapse of Axis, it was necessary for Allies to respect the Spanish neutrality.

Sources:

1. David J. Dunthorn, Britain and the Spanish Opposition 1940-1950, Palgrave, 2000

2. S. Grover Rich, “Franco Spain: A Reappraisal”, to: “Political Science Quarterly”, Vol. 67, No. 3 (Sep., 1952), pp. 378-398

3. Denis Smith, Diplomacy and strategy of Survival – British Policy and Franco’s

Spain, 1940-41, Cambridge University Press, 1986

4. Richard Wigg, The Survival of the Franco Recime, 1940-1945, Routledge, 2005