War History online proudly presents this Guest Piece from Joseph M. Durante

The German Revolution occurred shortly after World War I and included all the territories in the German Empire. In just a one year period, the revolution resulted in the creation of the Weimar Republic. While it is not disputed that there was political change and war, theorists such as Samuel Huntington, Karl Marx and Charles Tilly could have debated whether the German Revolution is actually worthy of the title of a “revolution.” Before addressing the theories, it is important to note the historical context and political landscape of WWI and the German Revolution.

The end of World War I destroyed many countries belonging to the German Empire in what is remembered as the War to End all Wars. Germany and the other Central Powers were losing the war by the year 1918, and the German military was losing faith in their leader, Kaiser Wilhelm II and the military leaders. Due to the eminent destruction of Germany, Prince Maximilian of Badan became Chancellor of the German Empire. United States President Wilson and Prince Maximilian tried to transform the German government from an imperial power into a parliamentary system using Wilson’s Fourteen Points towards the finalization of World War I. In 1918, when Maximillian of Badan became Chancellor; he was ordered to negotiate the Peace Treaty with the Allied Powers. President Wilson stated that there is to be no peace while Wilhelm II remained as the head of the state.

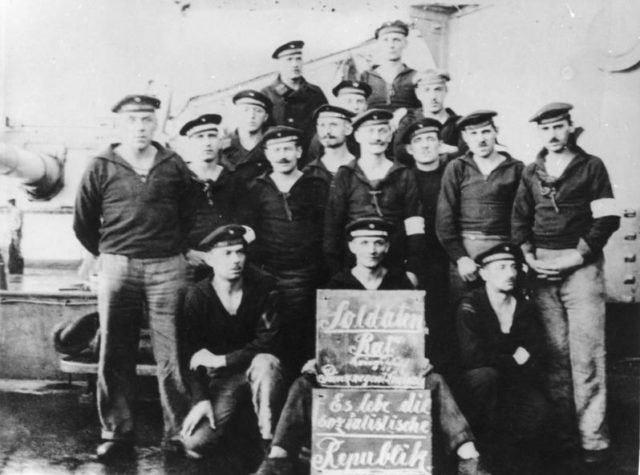

The German Revolution, also known as the November Revolution, and the first appearance of internal struggle, were caused by both failed policy and the lack of coordination between the German Supreme Command and Naval Command. On October 24th, 1918 German sailors disobeyed orders from Naval Command to engage the British Royal Navy in battle; they led a revolt at the naval ports in Wilhelmshaven located on the northern coast of Germany. This event would be remembered as the Kiel Mutiny and a beginning of the revolution.

On a different occasion, navel command in Kiel under Admirals Franz von Hipper and Reinhard Scheer engaged the British Royal Navy, without authorization from the German high command. This mutiny was strong enough to cause revolts and riots all throughout Germany demanding that the monarchy is destroyed. Sailors and citizens of the German Empire called for action against the monarchy because of the loss of the war. By November 4th, 1918, the acts of the Kiel Mutiny spread throughout Germany. By November 7th, 1918 major coastal and port cities such as Munich, Hanover, Brunswick and Frankfurt-am-Main, were seized. “Now word came in that Dusseldorf, Frankfurt-am-Main, Stuttgart, Leipzig and Magdeburg had all come under the control of quasi-revolutionary regimes; the imperial flag had been pulled down in those cities and the red flag hoisted.” All throughout Germany, riots and red flags were being raised. Those who opposed the revolutionaries were unarmed and seized under control by detainment.

Friedrich Ebert, the leader of the Social Democratic Party, and Prince Max planned to ask German Kaiser Wilhelm II to abdicate nearing the end of the war. However, the revolution reached Berlin by that time. Max, on his own accord, addressed the people the abdication of the Kaiser and cancelled the title given to the Prince of Prussia, Wilhelm the rightful heir to the throne. Shortly after Max gave his speech about the Kaiser, Ebert denounced the Empire and ordered that the government be given control to him and the Social Democratic Party.

Samuel Huntington mentioned that for revolutions to occur, through the modernization theory that the political development had lagged behind the social and economic development. By the end of the First World War, the German people believed that the government and the Kaiser had failed to protect them. After he went into hiding and it became clear that the Germans were losing the war and land around the western border of Germany was being destroyed and much of it was lost to the Allied Powers. The people truly believed that their government, their leaders, and their military could no longer support the political, social and economic lives of the people.

Huntington’s theory included a description of modernization and proclaimed that a revolution is both a characteristic and an aspect of modernization. He mentions a full scale revolution is a combination of a quick and very violent destruction of the existing political institutions. During the German Revolution, the complete destruction of the political institution really didn’t happen. At first, the group who came to power of the government was the Social Democratic Party (SDP). At the start of the war, in 1914, the Social Democratic Party (SPD) had split into two groups. The SPD stayed constant and supported Kaiser Wilhelm II, during the war, while their counterparts, the USPD, the Independent Social Democratic Party who supported peace. A leftist organization belonging to the USPD, the Spartacists or the Spartacus League, considered themselves to be Marxists.

Huntington and his Modernization Theory apply to the domestic problem and social problems. Unfortunately, the mutinies and uprisings weren’t brought about to change the social order but to change the governmental system. The sailors who mutinied believed the military officers and the government failed to achieve victory in the war. The Spartacus League was the group of people looking to change the government system to a communist or Marxist system, which would eventually bring about social change and social class change. Karl Marx, easily the most known philosopher, historian, and sociologist of the 19th Century wrote many popular writings discussing the bourgeoisie and proletariat social classes. One of his most famous work is, The Communist Manifesto, written along with Friedrich Engles, discussed a theory of revolution related to the rise of the proletariat or working class.

Marx mentions that the “bourgeoisie, historically, has played a most revolutionary part.” The bourgeoisie are those who control the means or production in a society. In the case of the German Revolution, the major factories were being controlled either by contract, or by direct control. These factories, because of the war, were producing weapons of war and the profits made by controlling the means of production were mainly spent on the war. Marx continued to explain the over production and the direct cause of it, “society suddenly finds itself put back into a state of momentary barbarianism.” Marx continues to say that it is, “a universal war of devastation had cut off the supply of every means of subsistence… and there is too much industry, too much commerce.” So, the Spartacus League would be the closest organization that would have wanted a full-scale change into communism and was the social change and linkage to revolutionary movements.

The Spartacus League, named after the ancient Thracian Rebel Spartacus who led the largest slave revolt of the era of the Roman Republic, and after the Russian Revolution of 1917, they started to think the correct course of action was to follow the Bolsheviks. The leaders and most prominent members of the Spartacus League were Karl Liebknecht, Rosa Luxemburg and Clara Zetkin. When the riots and mutinies occurred, the Spartacus League, along with the USPD, launched what was called the Spartacus Uprising. In January of 1919, the Spartacus Uprising was a power (political) struggle between Karl Liebknecht and his Spartacists against the SPD and Chancellor Friedrich Ebert. This was the political power struggle and while the two groups were fighting, unrest stood with the population of the German Empire.

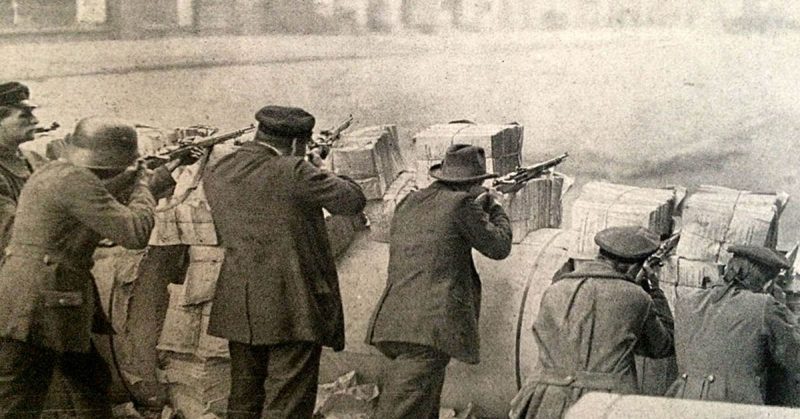

The Spartacus Uprising was planned to disrupt the Weimar Government by having ordered street demonstrations to protest businesses and to show popular unrest against the government. With the help of the Freikorps, or Free Corps, the administration of Ebert quickly destroyed the Uprising. Both Liebknecht and Luxemburg were arrested, kept prisoner, and killed while in custody of the Government and Zetkin went into exile to escape the Nazi Regime and which she died away.

The Spartacus Uprising was one of many uprisings around the German Empire. In order to avoid any more fighting and uprisings, a National Assembly took place in the city of Weimar and in return named the newly formed government, the Weimar Republic, or Weimar Regime was named. A parliamentary system was created and the Reichstag would be elected by proportional representation. The system had changed but uprisings still continued to happen around the empire. This is where Huntington’s theory plays a major role. The political system wasn’t destroyed completely, but reformed.

The Spartacists, had they been successful in obtaining power, they probably would’ve changed the social and economic state of the people. The political game of the German Empire shifted from being a conservative majority to a social-democratic elected government. According to Huntington, this was a complete revolution, for “the creation and institutionalization of a new political order.” However, Huntington would also suggest that this was not a full-scale revolution. The German Revolution did not involve “rapid and violent destruction of existing political institutions,” or “the mobilization of new groups into politics,” or “the creation of new political institutions.” But, all three of the events mentioned above must all occur to be considered a full-scale revolution. Huntington also mentions:

“If a new social force or combination of social forces (as in Germany in 1918-1919) can quickly secure control of the state machinery and particularly the instruments of coercion left behind by the old regime, it may well be able to suppress the more revolutionary elements intent on mobilizing new forces into politics (…the Spartacists) and thus forestall the emergence of a truly revolutionary situation.”

Based on Huntington’s theory of revolutions, it can be made that the German Revolution can and should be considered a revolution. For Huntington, he would have called the revolution a complete revolution, not a full-scale revolution.

Charles Tilly, another revolutionary theorist, brought about the ideas for the polities, contenders, and the state. “A contender for power is a group within the population which at least once during some standard period applies resources to influence that government,” and a polity “is the set of contenders which routinely and successfully lays claim on that government.” Contenders include the groups of the Spartacus League, the Social Democratic Party, and the Independent Social Democratic Party. The polity, who really threatened the current formation of the state, is the Social Democratic Party (SPD). The state would be the Empire and those who ruled it, Kaiser Wilhelm II, and the Monarchy.

The theories of Huntington, Marx and Tilly are all proven theories, but they do not have to all be present for a revolution to happen. In the end, there can be many factors for a revolution to occur. In the case of the German Empire; the result was the Weimar Republic. It is a Republic that gave a percentage of seats in the Reichstag to the percentage of votes they received as a political party. The governmental system changed and the monarchy was thrown out completely. Huntington explains the political struggle to keep up with the social and economic demand for change. Marx explains more generally the way the bourgeoisies use and control of the means of production and what a revolution against a non- communist system would look like. Tilly explains the groups of people that fought for power in the revolution, which all apply to the German revolution. In the end, it seems that the event certainly earned its name.

Bibliography

Watt, Richard M. The King’s Depart: The Tragedy of Germany: Versailles and the German Revolution. New York: Orion Books, LTD, 2003.

Vincent, Paul C. A Historical Dictionary of Germany’s Weimar Republic, 1918-1933. Westport: Greenwood Press, 1997. Print

Broue, Pierre. The German Revolution 1917-1923. Leiden: Kominklijke Brill NV, 2005. Print.

Harman, Chris. The Lost Revolution: Germany 1918 to 1923. London: Bookmarks, 1982. Print.

Henig, Ruth. The Weimar Republic. London: Routledge, 1998. Print.

“More Warships Join the Reds.” New York Times 11 Nov. 1918. Print.

“Red Flag Flying Everywhere in Kiel.” New York Times 10 Nov. 1918. Print.

“Ebert Says Germany Will Work for Peace.” New York Times 13 Nov. 1918. Print.

“Many German Warships Sunk by Crews During Revolution.” New York Times 17 Nov. 1918.

Stern, Fritz. Five Germany’s I Have Known. New York City: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007.

Laqueur, Walter. Weimar: A Cultural History. N.p.: Perigee – Penguin Books, 1976.

Marx, Karl, and Freidrich Engels. Manifesto of the Communist Party. Vol. 1. N.p.: Progress Publishers, 1948.

Huntington, Samuel P. Revolution and Political Order. N.p.: Yale University Press, 2006.

Tilly, Charles. Does Modernization Breed Revolution? New York City: Comparative Politics, Ph.D. Programs in Political Science, City University of New York, 1973.

All used citations are directly from the cited bibliography.