In the South Western Pacific Ocean, there is an island that is part of the Vanuatu archipelago, called Espírito Santo. Just off the coast of this island, there is a massive underwater dumping ground called Million Dollar Point, named so because of the millions of dollars worth of war material disposed of there.

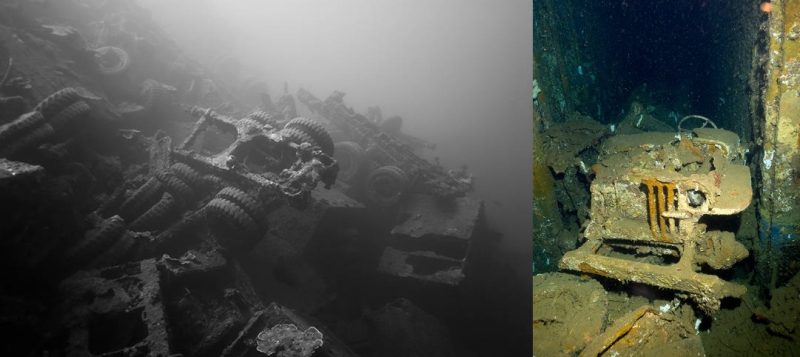

The dumping ground is a popular diving destination and divers report an unbelievable magnitude of wreckage: tractors, forklifts, six-wheel drive trucks, bulldozers, semi-trailers, jeeps, bound sheets of corrugated metal, sealed boxes of clothing, and cases of Coca-Cola.

The abandoned war materials were not discarded by the Ni-Vanuatu, the citizens of Vanuatu, nor by the Franco-British Condominium who ruled Vanuatu (known at the time as New Hebrides) from 1906 until 1980. No, it was discarded by personnel of a WWII American military base named ‘Buttons.’

After World War II had ended, at some point between August 1945 and December 1947, the US military immersed equipment, vehicles, and supplies under water at ‘Million Dollar Point.’

The travel writer Thurston Clarke describes the scene: The Seabees battalion built a ramp leading into the Pacific and every day the Americans soldiers drove bulldozers, trucks, tractors, jeeps, and ambulances into the channel, as the Seabees locked the vehicle’s wheels and jumped clear at the last second.

Engine blocks cracked and hissed, and the steam was rising as they hit the water. Some Seabees were actually weeping as the equipment forever disappeared in the murky depths. The Ni-Vanuatu who were witnessing the destruction of wealth, the likes of which their island would never see again, at least in their lifetimes, thought the Americans were going mad.

Despite salvage efforts, the dumping ground remains astonishing. One diving website states that Million Dollar the point is, “a monument to the futility of war.”

‘Buttons’ was one of two military bases that the Americans constructed on the archipelago. Shortly after ‘Buttons’ was built, the other, called ‘Roses’ was established on the nearby island of Efate. The military bases on Santo and Efate went up very quickly; in just weeks, as a matter of fact, and several islands within the boundaries of the Franco-British Condominium’s authority were transformed into lively American military hubs.

With the belief that a land invasion of Japan was inevitable in the continuance of the war – the Manhattan Project remaining top-secret, and indeed, thought would be a failure until the last tests had been completed – American manpower and equipment flowed into the archipelago region.

Between the military base at Efate and the airstrip on Santo there were half a million American soldiers processed. (In comparison, the entire native population of Vanuatu during this time was 60,000).

Images by Danger

As it turned out, however, the South Pacific theater had been oversupplied for its brief stint in the war, and combat-based military activity on Vanuatu was short-lived. Action quickly moved north toward Japan, and barely six months after the bases’ completion, Vanuatu comprised the extreme rear of the American line.

Although both bases performed important roles in the battles of Guadalcanal—Efate had the chief hospital, and Santo, which possessed the southernmost American airstrip, received wounded soldiers and combat equipment—they were primarily utilized as holding grounds and outfitting stations.

As a Major Heinl reported to National Geographic in August 1944, “jungles [were] cleared to make way for miles of stacked munitions and supplies.”

The storage on Vanuatu was never touched again, except to be thrown away. Despite the merchandise stockpiled on Santo and Efate, American industry continued to produce and ship new products; it was economically advantageous for the American military to use these rather than to rehabilitate the storage.

When the war ended, the Vanuatu holdings constituted a daunting pile of poorly organized, mislabeled crates.

To compound the problem, four years in the jungle had deteriorated some of the material; shipping costs were expensive, and only a handful of soldiers remained on the islands to sort and distribute the cargo. And as if that wasn’t enough, the enormous quantity of surplus—the “miles” of supplies—presented a major allocation dilemma. Santo and Efate were not unique in this situation.

The Philippine naval base at Calicoan, for example, was completed just two weeks before V-J day. Equipped for 5,500 men, the base immediately abandoned its initial mission—to support the final push in the Pacific.

![285169_10150343087467254_535262253_10132580_8135646_n[1]](https://www.warhistoryonline.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/64/2015/05/285169_10150343087467254_535262253_10132580_8135646_n1.jpg)

![205843_10150343087497254_535262253_10132581_6207335_n[1]](https://www.warhistoryonline.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/64/2015/05/205843_10150343087497254_535262253_10132581_6207335_n1.jpg)

![205927_10150343087522254_535262253_10132582_1539960_n[1]](https://www.warhistoryonline.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/64/2015/05/205927_10150343087522254_535262253_10132582_1539960_n1.jpg)

![226072_10150343087612254_535262253_10132587_6768472_n[1]](https://www.warhistoryonline.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/64/2015/05/226072_10150343087612254_535262253_10132587_6768472_n1.jpg)

![262506_10150343087687254_535262253_10132588_5416643_n[1]](https://www.warhistoryonline.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/64/2015/05/262506_10150343087687254_535262253_10132588_5416643_n1.jpg)

![262922_10150343087567254_535262253_10132585_2610484_n[1]](https://www.warhistoryonline.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/64/2015/05/262922_10150343087567254_535262253_10132585_2610484_n1.jpg)

![263391_10150343087797254_535262253_10132590_3494205_n[1]](https://www.warhistoryonline.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/64/2015/05/263391_10150343087797254_535262253_10132590_3494205_n1.jpg)

![292319_10150343087742254_535262253_10132589_1371536_n[1]](https://www.warhistoryonline.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/64/2015/05/292319_10150343087742254_535262253_10132589_1371536_n1.jpg)

![292650_10150342543727254_535262253_10126202_201090_n[1]](https://www.warhistoryonline.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/64/2015/05/292650_10150342543727254_535262253_10126202_201090_n1.jpg)

![292689_10150343087427254_535262253_10132579_2254176_n[1]](https://www.warhistoryonline.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/64/2015/05/292689_10150343087427254_535262253_10132579_2254176_n1.jpg)

![293025_10150342542752254_535262253_10126191_7973309_n[1]](https://www.warhistoryonline.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/64/2015/05/293025_10150342542752254_535262253_10126191_7973309_n1.jpg)