In the 1830s, a pastry chef made an appeal to the French king. As a result, France invaded Mexico, Corpus Christi in Texas was affected, a left leg still resides in two different countries, Cinco de Mayo came to be, and chewing gum was invented.

It all began in 1821 when Mexico broke away from the Spanish Empire. The result was a series of governments with about 20 different presidents over the next 20 years, as different factions vied for control of the new country.

In 1828, President Guadalupe Victoria kicked Lorenzo de Zavala (Mexico’s state governor) out of office. Unfortunately for Victoria, Zavala had the support of General Antonio López de Santa Anna. As a result, Mexico City was plunged into its usual chaos as supporters of both sides battled each other for control of the government.

In the aftermath, Zavala won. Neither side cared about civilian casualties or the damage they wrought – something all of Mexico would later regret for decades to come.

For among the things destroyed was a French pastry shop in the Tacubaya district belonging to a Monsieur Remontel. Not only had Mexican soldiers destroyed it, but they had also looted his shop’s supplies and merchandise. Furious, Remontel asked the government for compensation, but they ignored him.

In 1833, Santa Anna became president – the first of his 11 terms. Two years later, a large chunk of northern Mexico seceded to become Texas, so Santa Anna rode forth to take it back.

Though he defeated the rebels at the Battle of Alamo, they defeated him at the Battle of San Jacinto. The loss of Texas not only destroyed his reputation, it also plunged the country into further financial ruin.

Since the French had loaned millions of francs to bankroll Santa Anna’s attempts to retake Texas, they weren’t exactly happy, either. So when Remontel again asked for compensation in 1837, this time to King Louis-Philippe of France, he struck gold.

Baron Antoine Louis Deffaudis set sail and asked the new president, Anastasio Bustamante, to pay Remontel 60,000 Mexican pesos for his ruined shop. But the pastry chef wasn’t the only Frenchman to have suffered.

French businessmen had been forced to make numerous “loans” to government officials over the years, so Deffaudis demanded compensation for that, as well. Bustamante refused.

So Deffaudis returned on March 21st, 1838, with ten warships and a new ultimatum – cough up an additional P600,000 by April 15th, or else.

Bustamante still refused, so on April 15th, Captain Charles Louis Joseph Bazoch of the Herminie (a 60-gun French frigate) blockaded the major port of Veracruz. When negotiations failed, Louis-Philippe ordered a blockade of Mexico from the Yucatan to the Rio Grande.

Another meeting was held on November 15th, but the French now wanted an additional P200,000 to cover their expenses. The Mexicans balked, so Rear Admiral Charles Baudin attacked the city’s fort at San Juan de Ulúa and began the Battle of Veracruz on November 27th, which ended the next day when the city fell.

In the face of this threat, Mexico’s fighting factions finally united, so Bustamante told the French where to stick it. Santa Anna, who had retired in disgrace, offered his services to the government. Having no choice, they accepted.

He rushed to Veracruz and led a counterattack on November 30th. During his charge, French cannon fire blew out a finger on his right hand and hit his left leg above the knee, requiring amputation and a retreat (though not necessarily in that order).

The leg was preserved and buried with full military honors in Mexico City (where it remains to this day), forcing Santa Anna to use a wooden prosthetic. Instead of handicapping him, however, it made him a hero – the symbol of Mexico’s resistance to France. And with that, Santa Anna reentered politics.

But there was still the matter of the French. To get around the blockade, Mexicans had to smuggle goods in and out of Corpus Christi in the Republic of Texas (which hadn’t yet joined the American Union).

America also entered the fray. Distrustful of Mexico and anxious to maintain cordial relations with France, they joined the blockade by sending over the United States Revenue Marine (USRC) Woodbury – a 120-ton topsail schooner with four 12-pound and one 6-pound cannons.

This put the neutral Texans in a bind. There was concern over how the Americans might react. There were also fears that the French might blockade them, as well. Still, the money was good, so they welcomed the smugglers.

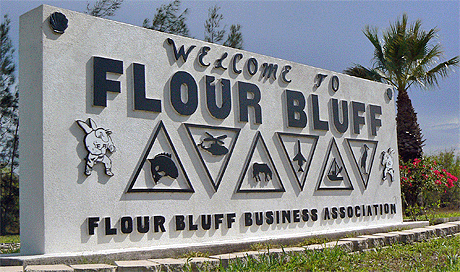

Things changed in July when Mexico sent soldiers into Corpus Christi Bay to secure their supplies. Texas responded by raising a large militia which reached the bay on August 7th. The Mexicans fled, leaving behind over 100 barrels of flour and some steam engine parts. And that’s how Flour Bluff got its name.

Desperate, the Mexican government appealed to Britain, which sent Ambassador Richard Packenham to mediate on December 22nd. The negotiations went on for three months, but Remontel finally got his money on March 7th, 1839.

Mexico also had to pay Deffaudis’ original demand of P600,000. In a generous mood, France let them off the hook for the extra P200,000 before withdrawing their fleet two days later. Mexico was now broke.

It got worse. In 1845, America annexed Texas. This led to the Mexican-American War (1846 – 1848) because Mexico still considered Texas to be theirs.

During the Battle of Cerro Gordo on April 18th, 1847 the Fourth Regiment of the Illinois Volunteer Infantry launched a surprise attack on Santa Anna’s camp. He escaped but left his leg behind – which is why it now rests in the Illinois State Military Museum.

The Mexican-American conflict was another blow to Mexico’s economy, leading to yet another war with France since the latter were still owed millions. This culminated in the Battle of Puebla on May 5th, 1862. Despite the odds, Mexico won, and they’ve celebrated Cinco de Mayo (5th of May) ever since.

But Texas was truly lost, so Santa Anna was again in disgrace. He was exiled several times, but never gave up his dreams of retaking Mexico. In 1869, the 74-year-old was living in Staten Island, New York when he had an idea.

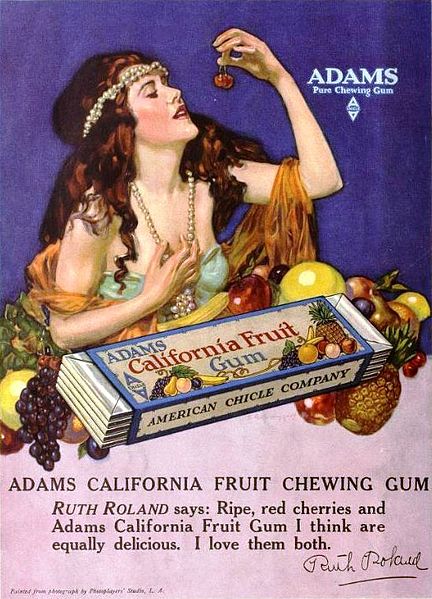

He imported tziktli (a gooey sap) to America, hoping to replace the rubber used in carriage wheels and make enough money to raise an army. He worked with Thomas Adams (an American scientist) on the formula, but failed.

Adams, however, developed Chiclets, and thus was born the chewing gum industry.