Helmets were first introduced to American soldiers in 1917, as a way of protecting servicemen from suffering head trauma while fighting in Europe. One of the most well-known helmets ever released is the M1. While effective, no one could have guessed it would actually increase the chances of someone dying on the battlefield.

The development of the M1 helmet

When the United States officially entered World War I in 1917, the military was without combat helmets. The soldiers arriving in Europe were issued British Mk I Brodie helmets or French M15 Adrian ones. The US was eager to create one that would protect troops from the horrors of trench warfare, but also distinguish American soldiers from those serving with other countries.

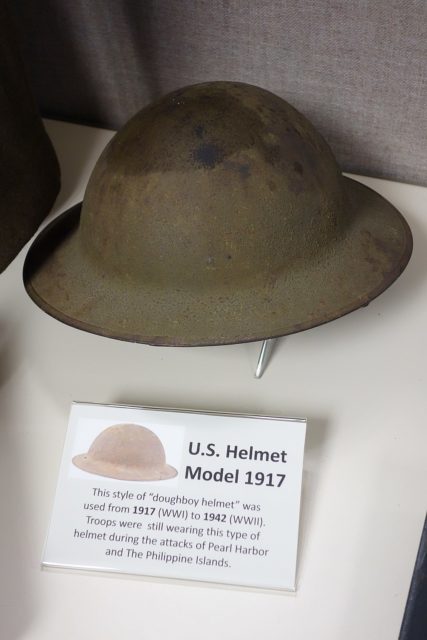

As a quick solution, the M1917 variant of the Brodie helmet was born. By the end of the war, 2.7 million had been produced. While the helmets offered moderate protection, they had several design flaws. They were not properly balanced and were ineffective against lateral fire.

Once the war was over, the US military launched a project to create a safe, sturdy and unique-looking combat helmet. Eventually, the Infantry Board settled on a better version of the M1917: the M1917A1, or “Kelly” helmet. However, when World War II began, officials knew they needed to prepare for the worst and resurrected the search for the perfect helmet. A report about a new design was published, which read:

“The ideal shaped helmet is one with a dome-shaped top and generally following the contour of the head, allowing sufficient uniform headspace for indentations, extending down in the front to cover the forehead without impairing necessary vision, extending down on the sides as far as possible without interfering with the use of the rifle or other weapons.”

The new helmet used the M1917 shell as its basis. The brim was trimmed off and replaced by a visor and “skirt-like” extensions that protected the entirety of a serviceman’s head. It was also given a liner and suspension system that was based off of the helmets worn by football players, with an adjustable chin strap to prevent it from moving.

Following its approval, the helmet entered production in April 1941 and was given the “M1” designation. It would see use with the US military until 1985.

Don’t lose your head

During WWII, 22 million M1 helmets were manufactured, and nearly every American throughout Europe and the Pacific was equipped with one. Additional ones were produced during the Korean War and Cold War, with improvements being made periodically.

Most liked the helmet, especially its coverage around the back of the neck and head and the addition of a visor to keep the rain out. The outer part could be removed from the inner plastic insert and filled with water for cleaning, shaving and even soaking tired feet. It was also used to dig holes and cook with.

The versatility of the helmet made it a huge asset, but there was debate about how to wear the chinstrap. Soldiers were told to wear it around their chin to secure the helmet, but rumors soon spread that it could easily pull the head back after an explosion, or that the enemy could grab it from behind during hand-to-hand combat and pull a soldier’s head back, exposing their neck.

The most dramatic story about the M1 chinstrap reported that the impact of a nearby explosion could break one’s neck when the heavy metal helmet was forced backward. This tale was supposedly false, but the Infantry Board eventually introduced a pressure-release buckle that allowed the chinstrap to manually release after an explosion.

Even without the threat of explosion, the chinstrap could potentially allow the helmet to slip down and impair a soldier’s vision, or a blow to the head could force the head backward and affect balance. Regardless of how it happened, all of these possibilities exposed a vulnerable portion of the body – the neck – leaving soldiers at risk of injury from gunshots, shrapnel or even an enemy wielding a knife.

To avoid the “snap-back” issue, most wore the chinstrap unbuckled or fastened at the back of the head, but going against protocol made this method equally dangerous to the front-facing chinstrap method.

Today’s high-tech helmets

Ultimately, the M1 helmet survived longer than the dangerous chinstrap rumors, as it was used by the US until the introduction of Personal Armor System for Ground Troops (PASGT) kevlar helmets in the 1980s. The new helmets provided increased ballistics protection and ergonomics.

The M1 is stilled used today in India, Turkey and Iran, and other variants, such as the Japanese Type 66, are modeled after the prolific helmet.

Modern kevlar helmets tackled the chinstrap debate head-on (no pun intended) by creating multiple straps to keep the helmet on during an explosion. The US Special Operations Command has developed the Advanced Combat Helmet, which allows communications devices to be integrated directly into the helmet.

More from us: The History of the US Navy’s TOPGUN School

The future of combat helmets looks even more high-tech, with models possibly including suspension technology and shock-absorbing webbing to reduce concussions and head injuries.