Before the official establishment of the position of Joint Chiefs of Staff in the United States Military in 1947, there served a man who was in all senses the first de-facto Joint Chief throughout World War 2.

There were Generals and Admirals such as MacArthur, Halsey, Nimitz, and Eisenhower, who would serve with great fanfare in this great war, but there was one man who would have the President’s ear throughout. Admiral William D. Leahy was a personal friend of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and although Admiral Leahy retired in 1939, Roosevelt would call upon this trusted confidant to help him run the war.

Admiral Leahy would exert great influence over the war effort and assist the President in making some of the most difficult decisions of the war. But the Admiral would often lament the one historically monumental decision for which he couldn’t persuade the President to come to his point of view.

From Ensign to Admiral

Born to an Irish-American family in 1875 Iowa, William Leahy would follow in his father’s footsteps and serve in the military. His father, a Civil War veteran, had attended West Point, and while that was initially the plan for Leahy, he would go on to attend the United States Naval Academy and graduate in 1897.

Serving as a Midshipman aboard the USS Oregon, he would see his only in person combat of his long, storied career when the Oregon made its famed run around the straights of Magellan and arrived in time for the Battle of Santiago during the Spanish-American War.

He was commissioned an Ensign in 1899 and would serve on 11 different ships over the next eight years to include those in service during the Boxer rebellion. In 1907, he would take a post as an instructor at the United States Naval Academy in the area of Chemistry and Physics.

In 1909, he would take back to sea and prior to the run-up to World War 1 would serve in a variety of fleet and administrative positions. It is during this time that he would establish a close relationship with then Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt. This meet up would prove to be of great importance for the future war ahead.

After America joined World War 1, Leahy would find himself in command of the transport ship USS Princess Matoika in 1918. During this tenure, he would be awarded the Navy Cross for his leadership and command transporting troops to France through U-boat infested waters.

After the war, he would bounce back and forth from duty at sea and high-level administrative positions within the Department of the Navy. By 1936, he would hoist his four-star Admiral flag aboard the USS California as Commander in Chief of the Battle Force.

Route to the Joint Chiefs

In 1937, he was appointed Chief of Naval Operations. He would serve in this role for two years as he sought to prepare the Navy for a future conflict that seemed just on the horizon. Admiral Leahy would be put on the retired list in 1939 with long-time friend Roosevelt letting him know not to get to settled into being retired should a war break out.

He would serve as Governor of Puerto Rico in 1939 and then Ambassador to Vichy France in 1941 before being recalled to Washington in early 1942.

Roosevelt, his friend and Commander in Chief, desired to have a point of contact for the three service Chiefs, Admiral Ernest King of the Navy, General George Marshall of the Army, and General Henry Arnold of the Army Air Forces. It is reported that the service Chiefs were not fond of this idea, but agreed when the widely respected Admiral Leahy was picked for the task.

In July of 1942, Admiral Leahy was appointed to the position of Chief of Staff to the Commander in Chief. It was actually Leahy who had proposed the idea of the Joint Chiefs to Roosevelt as it allowed for better coordination of the war effort. And with Admiral Leahy at the head, it was here that he would serve as the first de-facto Joint Chiefs of Staff and hold the ear of one of the most powerful men on the planet.

As the war continued, Admiral Leahy would almost always be at Roosevelts side. He traveled with him to the Middle East for the Tehran Conference and helped guide the policy that would not only navigate the war but set the stage for the post-war world.

He was seen as such a pivotal figure for the war effort that he was asked to go home to Iowa during the D-Day invasion as it was thought that it would lead any German agents to believe such a monumental attack couldn’t take place while Admiral Leahy was away from Roosevelt.

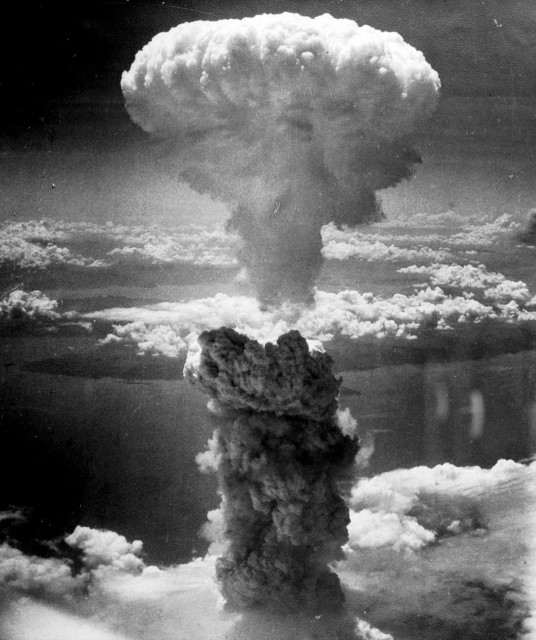

The Atomic Bomb and Admiral Leahy

In December of 1944, Leahy was promoted as the United States Navy’s first Fleet Admiral. Despite this 5 star ranking and his personal relationship with FDR, Admiral Leahy couldn’t get the President to agree with him when it came to the future notion of dropping the Atomic bomb on Japan.

Admiral Leahy believed that Japan was already on the verge of defeat, and they could be talked into surrender without dropping the Atomic bomb and without an invasion of Japan. When FDR died in April of 1945, he continued his service to the Presidency, but the decision to drop the bomb would fall to President Truman.

The rest is history as Truman made the fateful decision and one can’t help but wonder if history would have taken a different course if Admiral Leahy’s longtime friend had still been the President in August of 1945.

For Admiral Leahy’s part, he would go on to lament that decision as he said, “It is my opinion that the use of this barbarous weapon at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan. The Japanese were already defeated and ready to surrender because of the effective sea blockade and the successful bombing with conventional weapons… My own feeling was that in being the first to use it, we had adopted an ethical standard common to the barbarians of the Dark Ages. I was not taught to make wars in that fashion, and that wars cannot be won by destroying women and children.”

The world will only know the history that we were given and to speculate how the alternative would have turned out is educated guessing at best. But beyond dispute is the fact that the first Joint Chiefs of Staff had an immeasurable impact on the conduct of World War 2.

He might have disagreed with the decision to drop the Atomic bombs, but that course of action rests in a future we will never know.