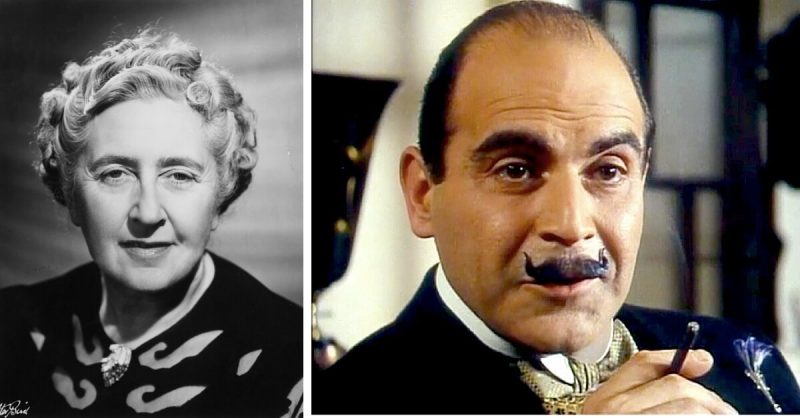

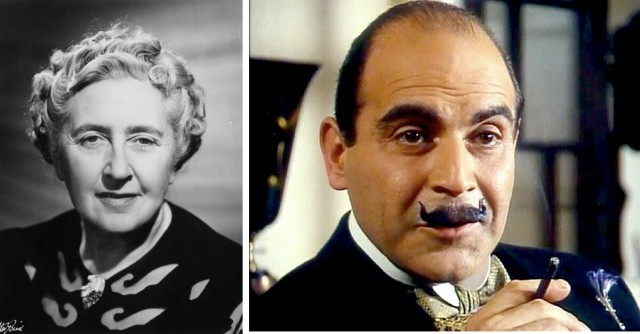

Well-founded speculation abounds that famed mystery author, Agatha Christie, used her experiences as a war time nurse in plotting and detailing the killings in her novels. While most point to WWI, at least one source says it was rather WWII in which she learned most about poisons – her favorite method of murder.

Christie was brought up in Torquay on the coast of Devon, England, in a somewhat well to do family. Her education consisted of several years with a governess, learning math and writing at a school in town, and finishing school in Paris.

Her focus at school in Paris was in music and she became an accomplished pianist. Some say she met a Belgian gendarme refugee while playing piano at a party and it was upon this man that she based her most famous character, Hercule Poirot.

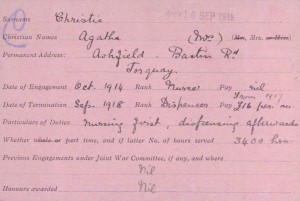

At some point prior to the Great War, Christie received her certification as a First Aid and Home Nurse, although she infers in her autobiography that this education would be little to prepare her for her duties during the war.

Just after her fiancé flew off to France with the RAF, she joined the Red Cross Voluntary Aid Detachment as a nurse. She was one of 90,000 Brits to do so. She went to work at the local town hall that had been converted into a hospital of 50 beds.

There she worked in the operating room, attended to the gruesome clean-up of amputations, and assisted the severely wounded soldiers.

According to Annabel Venning of The Daily Mail, Christie soon bucked up to the challenge, but of her first surgery, she commented , “Suddenly the theatre walls reeled about me . . . It had never occurred to me that the sight of blood or wounds would make me faint.”

While her hospital experiences and the doctors she met there helped inform her writing, it wasn’t until she returned to the hospital after a bout of sickness that she found some of her real inspiration – poisons.

She had been home sick with the flu for several weeks before returning to the hospital to find that they had completed the new dispensary. She studied for and passed exams so that she could leave the monotonous work she had been doing to work there. She learned pharmacology from the pharmacists in the dispensary and from a local druggist.

Her position was as a dispenser, which entailed mixing the medicines and tonics that make up a prescription. As a volunteer, she had worked 3400 hours without recompense, but as a dispenser, she earned £16.

Prior to the war, she had tried and failed to publish a novel. While serving as a nurse, her sister dared her to write another. She used her newfound knowledge, plus a recent interest in mysteries, to inspire her first successful mystery novel, The Mysterious Affair at Styles in which we first meet that Belgian refugee, Poirot, and in which he solves a case involving poisoning.

She said, “Since I was surrounded by poisons, perhaps it was natural that death by poisoning should be the method I selected.”

Following WWI, she became an incredibly successful novelist. When the next World War came around, she furthered her education of poisons; likely paying even more attention now that it was her method of choice.

She worked at the pharmacy in the University College Hospital in London. The chief pharmacist there, Harold Davis, who would later become the chief pharmacist for the UK Mini suggested to her that thallium could be used as a poison. After using it in her novel, The Pale Horse, doctors who had read her very detailed descriptions of its effects were able to properly diagnose real life victims. A one year old little girl was saved because her nurse was reading The Pale Horse at the very time the girl was under her care.

It was not only tools of murder that she took from her wartime hospital and pharmacy experiences; she also used them to form characterization. Writer Michael C. Gerald surmises in an article for Pharmacy in History that Christie formed a distrust of medical professionals through working with them and that this distrust plays out in her books. He points out that many of her villains are doctors and scientists and points to this quote from one of her books:

“There seems to be a kind of fashion in drugs like everything else. Doctors seem to follow one another in prescribing like a lot of sheep.”

Of Christie’s 85 books, 66 were detective novels. Forty one of those 66, involved poisons. Twenty four of her 148 short stories did as well.

Agatha Christie wasn’t all poison, murder, and intrigue, though. She knew how to have fun. She was one of the very first Britons to learn to surf standing up. Imagine that.

Sources:

- http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/books/11092925/How-WW1-shaped-Agatha-Christie-and-Poirot.html

- http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2608194/How-Agatha-Christies-agonies-war-nurse-helped-inspire-Poirot-Real-story-The-Crimson-Field-remarkable-TV-gripping-millions.html

- http://classprojects.kenyon.edu/engl/exeter/Kenyon%20Web%20Site/Chris/Learning%20to%20Write.html

- http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/agatha-christie-is-born

- http://www.jstor.org/stable/41109449?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

- http://www.jstor.org/stable/41111363?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

- Eunice Bonow Bardell – Dame Agatha’s Dispensary Pharmacy in History, Vol. 26, No. 1 (1984), pp. 13-19

- Michael C. Gerald – Agatha Christie’s Helpful and Harmful Health Providers: Writings on Physicians and Pharmacists Pharmacy in History, Vol. 33, No. 1 (1991), pp. 31-39

- The New Scientist. Aug 10, 1978. 64 pages, Vol. 79, No. 1115. ISSN 0262-4079