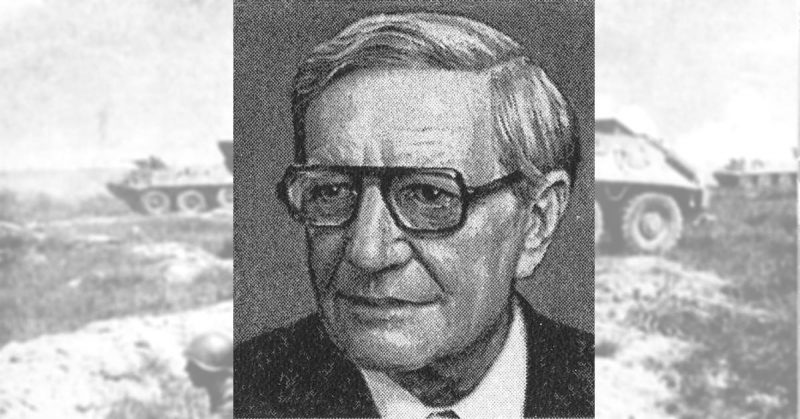

Harold “Kim” Philby, British journalist and intelligence agent, is one of the most famous traitors of the Cold War. Part of the infamous Cambridge spy ring, he used his position at the heart of the British establishment to feed information to Soviet Russia.

Does Kim Philby deserve to be labelled the biggest traitor ever?

A Very British Background

Kim Philby embodied the 20th century British established, as the nation faded from a global empire, through a prominent position in the Second World War, into a secondary player in the Cold War. Born on 1 January 1912 to a member of Britain’s Indian Civil Service, his nickname was taken from a Rudyard Kipling novel. He attended private schools and then Cambridge University, receiving a prestigious education that embedded him in Britain’s social elite.

Early Espionage

The nature of espionage, with its secrecy and lack of complete records, makes it hard to be certain about Philby’s story. Though his fellow Cambridge graduate Guy Burgess has often been credited with recruiting him to Soviet intelligence, the real link was probably his first wife Litzi, through whom he was recruited in 1934. A true believer in Communism, and an anti-Fascist activist alongside Litzi, Philby was a natural recruit for the Soviets.

One of Philby’s first tasks was to make a list of others worth recruiting. These included Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean, men who would become hugely significant later in his life.

After studying Russian at the School of Slavonic Languages in London – a top recruiting ground for British diplomats and intelligence operatives – Philby went into journalism. Travelling to Spain in February 1937, he reported on the Civil War from the side of General Franco’s right-wing forces. Franco had support from Nazi Germany, including military equipment, and Philby provided information on this to both British and Soviet intelligence. He was now a double agent.

The War Years

Philby was shocked by the partition of Poland between Germany and Russia at the outbreak of World War Two, and stopped reporting to his Russian handlers.

Meanwhile, he was recruited to the British War Office, and from there to the newly formed Special Operations Executive (SOE) in July 1940. This began his rise through the British intelligence services. Initially tasked with training saboteurs to be deployed against the Germans, he then moved on to work in counter-intelligence.

Given his new role, the Soviets were quick to reactivate Philby as one of their agents. With the USSR now fighting against Nazi Germany, Philby started working for the Soviets again. But they became suspicious that he was feeding them false information, as he insisted that Britain was not training agents to infiltrate Russia.

In August 1945, Philby’s cover was almost blown. Konstantin Volkov, a Russian defector, offered to reveal the names of Russian operatives within British intelligence. Fortunately for Philby, he was given the task of bringing Volkov in. By informing the Russians and moving slowly, he ensured that Volkov never reached the west, and so saved his own skin.

Shortly after, another defector mentioned a British journalist who had spied for the Russians in Spain – the first clues to Philby’s treachery. But for now he was still seen as loyal, and in 1946 he was awarded the OBE.

Our Man in Washington

After serving for a short time in Turkey, Philby was made chief British intelligence representative in Washington in September 1949. As well as liaising with the CIA, he had access to sensitive information travelling between Washington and London, making him hugely valuable to the Russians. But even before he reached Washington, the seeds for his downfall had been sown.

By intercepting Russia communications, the British had discovered that there was a mole in their embassy. Philby realised that this was Donald Maclean, and was left with the difficult task of trying to identify the mole while also trying to protect Maclean.

This situation was made worse by the arrival in October 1950 of Guy Burgess – unstable, alcoholic, and yet another Russian spy in the embassy.

In May 1951 Burgess was sent back to Britain after offending the Americans. Maclean was also back in Britain, and Philby knew that he was about to be interrogated as chief suspect in the mole investigation. Philby contacted Burgess with the intention that he get Maclean to escape alone. Instead Burgess fled to Moscow with Maclean.

Under a Cloud

Burgess’s departure with Maclean threw suspicion onto Philby. He was interrogated by MI6, and resigned before he could be dismissed. Lack of evidence meant that he was officially cleared of all charges in 1955.

In the meantime, he returned to journalism. In August 1956 he moved to Beirut as Middle East correspondent for The Observer and The Economist.

No longer employed by MI6, he also lost contact with Soviet intelligence.

Discovery and Flight

In 1961, Major Anatoliy Golitsyn of the KGB defected to the USA. Questioned by British agents, he confirmed suspicions that Philby had been the “third man”, spying for the Russians alongside Burgess and Maclean. Nicholas Elliot, an MI6 agent who was friends with Philby, was given the job of obtaining a confession. Philby confessed to Elliot in late 1962, but would not then sign a written confession, instead arranging another meeting for this.

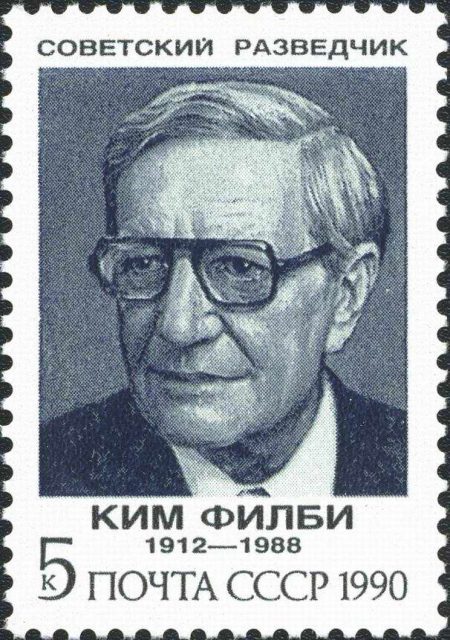

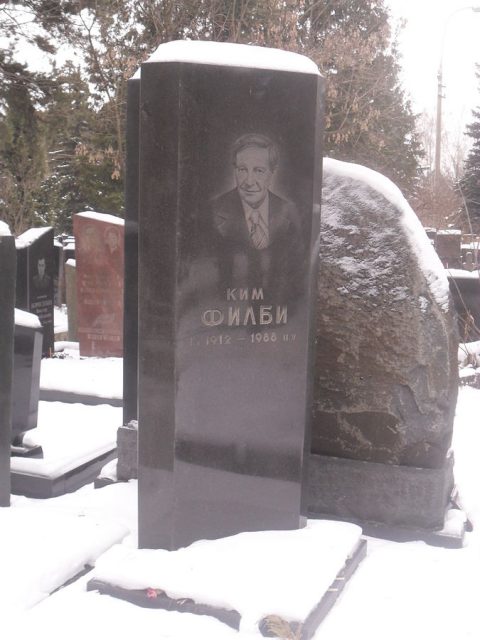

On 23 January 1963 Philby disappeared, slipping out of Beirut and making his way to Russia. He lived there until his death in 1988, disappointed by what he saw and by the Russians’ refusal to use him within the KGB. He had hoped to become one of their greatest assets, but instead found himself treated with suspicion. The KGB were unwilling to trust a man who had already roused suspicions, and who had a history of playing both sides.

The Greatest Traitor?

Was Kim Philby the biggest traitor ever?

His treachery to his country is beyond doubt, though its impact is hard to judge. Historian Michael Smith has argued that his actions led to the death of perhaps hundreds of agents, but given the nature of espionage this is impossible to prove. Philby remained loyal to his Communist beliefs, even though he had to hide them for decades. But his treatment of his family, who he abandoned to flee to Russia, counts heavily against him.

Philby was hugely embarrassing to the British, and this has expanded his reputation. But with so many men and women working in secret, betraying friends, nations and principles for the sake of espionage, is he the biggest traitor ever? Almost certainly not.