Equally helpful in trying to unravel the Tonkin mystery at the time was John Galloway’s 1970 work The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution. Galloway reported that Fulbright, in his continuing quest for more information, tasked the Senate Foreign Relations Committee with getting to the bottom of the Tonkin affair. Galloway revealed that many members shared Fulbright’s sense of chagrin over how the original Tonkin Resolution hearings were handled (Galloway 102). He wanted to hold new hearings, examine any evidence which might poke holes in the administration’s case and shed light on the decision making process in place at the White House and the Pentagon. In preparation for the 1968 hearings the committee unearthed a letter written by Admiral Arnold True.

True was the author of the manual of conduct used by destroyers like the Maddox and Turner Joy, and an authority on international law. In 1964 Secretary McNamara testified that on the day of the first attack Maddox had fired warning shots at advancing North Vietnamese patrol boats. No such thing, Galloway claimed. Admiral True asserted that under international law, warships didn’t have to fire warning shots if confronted at sea (104). Galloway also disclosed details of an anonymous letter delivered to the committee urging it to demand the Pentagon provide the ‘Command and Control’ report of the Tonkin incident, which included transcripts of conversations between Johnson, McNamara and Admiral Grant Sharp, Commander In Chief, Pacific Fleet. The conversations, argued Galloway, contained acknowledgements by officials that the second attack was probably imaginary (105). The timing of these conversations, he said, was important. The President had authorized a retaliatory raid to coincide with a televised address to the nation.

Without confirmation of a second attack, the speech would have to be cancelled and the planes ordered to stand down. Galloway points out, again quoting the unnamed source that even though Sharp personally harbored some unanswered questions on the details of the incident, he confirmed the second attack to McNamara. McNamara passed the news to Johnson, who unleashed the air strike and made his address (105). The revelations undermined the government’s case about the second attack. Galloway also reported that the Johnson administration was trying to head off the new hearings altogether. It sent Deputy Defense Secretary Paul Nitze to see Fulbright who told him the administration had iron-clad proof of the second attack. The proof consisted of intercepted North Vietnamese radio transmissions claiming the assault had been carried out by two Swatows, Chinese built gunboats, and a patrol boat. The problem, argued Galloway was that Swatows don’t carry torpedoes, and the patrol boat in question only carried two. How, he wondered, could McNamara testify to Fulbright’s committee in 1964 that Maddox and Turner Joy had been subjected to repeated torpedo attacks? (107).

Galloway confirmed that when Secretary McNamara reappeared before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in 1968 he repeated his earlier claim about a second attack and offered the corroborating testimony of Commander Herrick, who now said the only doubts he had that night in the Tonkin Gulf was the number of torpedoes fired at the Maddox and Turner Joy (New York Times February 24, 1968). McNamara argued the ships were in international waters at the time, that they had no part in the commando raids on North Vietnam, and that any insinuation that the US might have provoked the attack was, in his words, monstrous. He had the committee at a disadvantage, argued Galloway, because he denied Fulbright and his colleagues’ access to the Command and Control document they had requested, citing security clearance issues. Consequently, concluded Galloway, the committee and its staff were forced to rely on information tendered voluntarily by the Defense Department (132). And when the committee wrapped up its investigation in December, 1968, Galloway concluded, it really had nothing to show except what the Johnson Administration had chosen to let them see.

It could not prove that there wasn’t a second attack, even though the earlier misgivings by the captain of the Maddox, the faulty sonar readings, cables alluding to the firepower limitations of the North Vietnamese Navy and the discovered transcripts of a captured North Vietnamese naval officer suggested it. The evidence seemed to be, in Galloway’s words concealed in ‘the labyrinth that surrounds the Department of Defense’ (137). And Fulbright, unable to penetrate that labyrinth could only express during the hearings his regret at having been the vehicle which took the Tonkin Resolution to the floor of the Senate and defended it. It would take time before all the facts would be known, but Fulbright and the Senate Foreign Relations Committee had run out of time, just as the American people had seemingly run out of patience.The Washington Post may have delivered the coup de grace to suspicions about the second raid when it editorialized that the hearings threw into question an incident which led to a resolution demonstrating national unity. “That virtue has been diminished by the attacks made on the integrity of the foundations of the Tonkin Gulf Resolution. Senators…have impaired the force and effect of assertion of national purpose. And the country thereby is left facing dangers far more serious than those it confronted in 1964” (Washington Post February 25 1968).

Success at penetrating the ‘labyrinth’ as Galloway called it, proved difficult in the years immediately after 1968. There were a spate of works between 1971 and 1975; Anthony Austin’s The President’s War, Eugene Windchy’s Tonkin Gulf and Gerald Kurland’s The Gulf of Tonkin Incidents, but none of them really were able to answer the questions raised by Galloway in 1970: why had Captain Herrick expressed initial misgivings about the second attack, only to reverse himself under oath before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee? Why hadn’t the Defense Department been called upon to explain the cables it possessed identifying the North Vietnamese ships allegedly involved in the second attack and the limited firepower they had brought to bear on the two US warships? And finally, why hadn’t anyone taken a closer look at the interrogation transcripts of captured North Vietnamese personnel which threw the attack into question? Galloway had asked the right questions in 1970. Getting to the answers was proving to be difficult. Austin and Kurland’s work focused in part on the crew of the Maddox, some of whom were skeptical of a second attack. Austin’s work belies a deep suspicion of the Navy’s actions.

He argued the service felt left out of the action in Vietnam in 1964. After all, the Army, Air Force and the C.I.A. were there. What about them? The Desoto patrols were, he claimed, were an attempt by the Navy to establish a presence and play a role in the O-Plan 34A operations. The Navy, he said, even went so far as to disregard Captain Herrick’s warning that the Desoto operations would be viewed by North Vietnam as part and parcel of the O-Plan activities and ordered him even further into harm’s way. He claimed the Navy forced events in the Tonkin Gulf to provoke a confrontation with the North Vietnamese, and that it manipulated the news of the attacks in order to manipulate the actions of policy makers in Washington. In doing so, argued Austin, the Navy deceived the Executive Branch, which in turn had to deceive Congress. Gerald Kurland wasn’t quite as suspicious of the Navy, preferring instead to accept the fact that atmospheric conditions in the Gulf that night had caused sonar operators to misinterpret what was on their screens. Windchy’s work looked at the thought process inside the White House in 1964. He claimed the Johnson Administration had grown pessimistic about the situation in Vietnam, and concluded it could only be won ‘if a bigger effort were made’ (305). He outlined the thinking behind the need for a resolution containing ‘an all inclusive war authority to present to Congress at some appropriate time’ (311). To Windchy, the events in the Tonkin Gulf coincided with what the Johnson Administration perceived as a crossroads in Vietnam. The North Vietnamese and their Viet Cong surrogates were getting stronger; the government of South Vietnam was getting weaker; and then, said Windchy, in the words of one Johnson Administration official, ‘…we had the Tonkin Gulf’ (317). But despite the digging, the labyrinth Galloway spoke of couldn’t be breached. The Defense Department continued to cling to its assertion that at the end of the day, there was a second attack. The questions left unanswered in 1968 would remain so until years after the war had ended and the pain and passion it had aroused had reached a manageable level.

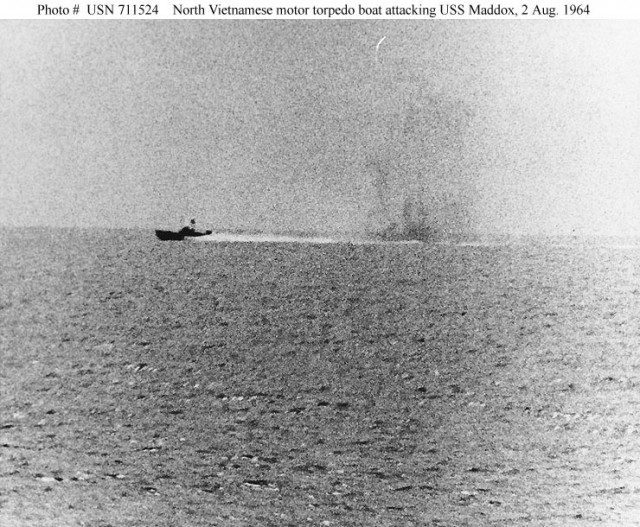

The first significant break appeared in Anthony Pitch’s 1984 article in US News& World Report. It revealed “a growing consensus within government that North Vietnam had assumed the Desoto patrols were associated with the OPLAN 34A raids…and that North Vietnamese action on August 2 was a retaliatory act” (61). The response by the Johnson administration was to continue both the OPLAN raids and the Desoto missions. There was no intention, in the words of Secretary of State Dean Rusk “…of yielding to pressure” (61). According to the Defense Department, when night fell in the Tonkin Gulf on August 4th, Maddox and Turner Joy were fending off an attack by North Vietnamese patrol boats, which according to a message intercepted by the National Security Agency, had been given the destroyers’ coordinates and told to prepare for combat. But the US News article suggested North Vietnamese intentions were unclear. A senior CIA analyst on duty in Saigon at the time saw the same message and interpreted it as an order to investigate, not attack the warships. “There was no unequivocal indication that the North Vietnamese had been ordered to initiate combat action”, he said (62). Pilots flying air cover that night were equally skeptical. One pilot, Commander James Stockdale, flying his second photo combat reconnaissance mission in as many days saw the destroyers’ wakes very clearly, but no enemy ships.

The photographs later confirmed his visual impressions (62). US News also elaborated on the skepticism Captain Herrick felt about the attack from his position on the bridge of the Maddox. “Most of the Maddox’s if not all of the Maddox’s reports were probably false”, Herrick went on record as saying (63). That Herrick shared his misgivings as well has his confusion with his superiors is well known. What wasn’t well known, at least until 1984 is why those misgivings never managed to get to policy makers in Washington. For a while, claimed US News, even Secretary McNamara was unsure of the accuracy of the news from the Gulf, and sought clarification by trying to establish direct voice contact with the Maddox. Although technically possible, the move constituted a breach of the military principle of chain of command, and offended Vice Admiral Roy Johnson, commander of the Seventh Fleet. Johnson told McNamara such communication could not be arranged, an assertion he later admitted was not true (63). McNamara then reached out to Admiral Sharp about the reports from the Gulf of Tonkin. Pressed by McNamara, Sharp, according to US News reported that the latest message from the destroyers “indicated a little doubt on just exactly what went on.” Was there a possibility that no attack occurred? McNamara asked. “Yes,” Sharp replied, “I would say there is a slight possibility.” (63)

His assessment carried particular weight, but according to US News the clinching pieces of evidence were enemy naval communications intercepted during the battle. They read: “have engaged enemy and shot down two planes. Starting out on hunt and waiting to receive assignment. Morale is high as men have seen damaged ships.” (63) McNamara’s contention such cables were unimpeachable evidence left many intelligence officials then and now unconvinced. Several National Security Agency field stations reported intercepting the same message on August 2. Only one listening post, located in South Vietnam, said it was acquired on August 4. Years later, according to US News, former CIA Deputy Intelligence Director Ray Cline looked at the cables and concluded they couldn’t be referring to the August 4 incident, but rather the August 2 engagement. “Things were being referred to which, although they might have been taking place at the time, could not have been reported back so quickly.” (63) In early 1972, Louis Tordella, Deputy Director of the National Security Agency told the Senate Foreign Relations Committee that there was no doubt in his mind that references in the August 4 intercepts to “enemy planes” and “damaged ships” pertained to the August 2 engagement. (64).

This story will be continued on Tuesday!

JOHN MORELLO, PH.D. SENIOR PROFESSOR OF HISTORY for War History Online