The Romans and the Gauls had a bitter rivalry that lasted as long as any other in the world. One of the most humiliating events in Roman history was the nearly total capture of Rome by the Gauls under Brennus in 390 BCE leading the Romans into an embarrassing payoff for peace.

Ever since, the Romans and Gauls were quick to fight each other, with the Gauls always on the lookout for easy loot and the Romans looking to add more land and rid the world of the loathsome Gauls.

Though the Romans definitely came out of the 390 BCE engagement licking their wounds, they had grown in the following century and some before the battle of Telamon.

Far removed from the phalanx system the Romans had worked out a new manipular battle formation during their arduous wars against the Samnites.

After conquering their greatest Italian rivals, the Romans put their new manipular formation to the test against the invading Pyrrhus of Epirus, a proven commander with an elite army and elephants. The Romans proved their bravery and determination and finally ousted the great commander.

Rome then engaged in their first major war outside of Italy against Carthage. gaining vital command experience, the Romans came out of the war more assured in their naval capabilities and with holdings in the island of Sardinia.

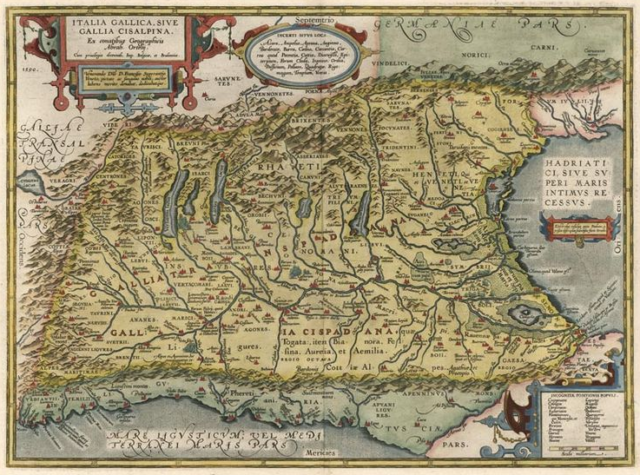

The Gauls knew of Rome’s growth but did not see it as imposing, but rather saw Rome as an even more appetizing target for plunder. The Gauls were still a major presence in northern Italy and the Boii tribe hoped to gather a group to strike straight at Rome itself. The Boii gathered allies from the Insubres and Taurisci tribes and received many warriors from the Gaesatae tribe.

The Gaesatae were some of the most feared warriors of this period, renowned for fighting nearly or completely naked and being in a warlike trance during battle. it is possible that they took some types of drugs to numb the pain from battle wounds as they seemed to be able to continue fighting through many injuries.

The combined Gallic army contained 50,000 infantry and 20,000 cavalry, more than a match for a standard Roman army typically half that size or less. The Romans, fortunately, had multiple armies in the area, two in northern Italy and one stationed on the nearby island of Sardinia if needed.

The Romans knew of the massive Gallic invasion and gathered thousands of allied forces to support their own troops. One such army ran into the Gallic force and the two armies set up camp.

The next morning the Romans saw what appeared to be a cavalry rearguard of the fleeing Gauls. The set up to chase through a wooded and hilly area but were ambushed by the waiting Gallic infantry.

About 6,000 Romans were killed but likely thanks to the manipular formation, they were able to reform and occupied a nearby hill. From here they withstood more assaults until a full consular army under Lucius Papus arrived.

The prospect of facing a fresh army and the recovering army from the previous battle was too much for the Gauls, especially as they had already collected a decent amount of booty from raiding.

They decided to march home to resupply and store their loot before striking again. They left during the night with the Romans easily following the tracks of such a massive army.

The Gauls were deep in Roman territory and had to wind through the hills, but had a clear shot home along the western coast of Italy, or so they thought. Pretty soon the Gauls’ vanguard ran into Roman cavalry scouts, a confusing find as they should have put some distance between the other two Roman armies.

The scouts actually belonged to a third Roman army, under Gaius Atilius Regulus, fresh from the nearby island of Sardinia, they coincidently landed just north of the advancing Gauls. The Romans now had three armies surrounding the Gauls; there were some hills, but no way for the Gauls to escape. Messages were sent between the Roman commanders and an attack was hastily organized.

The Gauls sent their sizable cavalry force to secure a nearby hill vital to any further advancement while they formed two lines in opposite directions and anchored their flanks with wagons and chariots.

The fight on the hill was fiercely contested by the Roman cavalry led by Regulus and probably the light infantry as the cavalry numbers do not make enough sense for the Roman cavalry to hold the ground alone.

Nevertheless, it was a tough struggle and for a long time all the waiting Gallic infantry and slowly advancing Romans could do was watch the struggle. Papus, sent his own cavalry to aid in the hill-top fight and they would eventually secure the hill after brutal fighting that would see the beheading of Regulus.

The brave Gallic infantry was more than ready to receive the attack of the Romans, despite the Romans having maybe 10-20,000 more men. All the bravery of the Gaesatae could not prepare them to deal with the new Roman way of combat that led with torrential volleys of javelins from both the skirmishers and the front ranks of infantry.

With no protective armor, the Gaesatae were decimated by the barrage, those who weren’t killed were likely severely wounded and the Romans were able to engage with a significant advantage.

The Roman style of combat with the heavy use of shield defense and swift stabbing motions of their swords countered the long windup attacks of the Gallic longswords.

Even with all the Roman infantry advantages, the fight was closely contested until the victorious Roman cavalry were able to swing down and find gaps in the wagons to flank the Gauls. The disposition of the troops in the battle meant that the Gauls were largely cut down where they stood, with little chance to flee.

Around 20,000 men escaped with the rest killed or captured, compared to around 10,000 Roman casualties, fairly high given that they had the numbers and positional advantages.

The Roman victory greatly reduced the number of enemy warriors in northern Italy and a quick punitive campaign was organized, primarily aimed at the Boii. The Romans were well on their way to finally securing the rest of Italy, but in 218 BCE, the terrifying Hannibal, and his elephants put that goal on hold for a few decades, though the Romans would continue to wage war against the Gauls in Italy throughout the second war against Carthage.

The Battle of Telamon was a great example of the efficiency of the Roman military structure. Commanders may not have had the largest single armies, but effective communication resulted in the trapping of a large and dangerous army and further cooperation allowed the armies to charge into the front and rear of the Gauls simultaneously.

With the exception of Hannibal’s victories, the Roman armies would prove to be a nearly unstoppable battering ram on the battlefield, winning victory after victory simply by way of their superior organization and adaptability.

By William McLaughlin for War History Online