Fighting Joe Hooker is one of the stranger figures of the American Civil War. As a general, he was aggressive in both his outlook and his tactics. However, when given command of the Union Army of the Potomac, that aggression evaporated. He acted with timidity and defensiveness that brought failure, but not the end of his war or his military career.

Origins of a Soldier

Like many officers leading both armies in the Civil War, Hooker was a graduate of West Point Military Academy. After leaving the academy, he was a lieutenant in the artillery, fighting against the Seminole Indians, then served on the Canadian border and as an adjutant at West Point.

In 1846, war broke out with Mexico. Hooker served on the staff of various commanders, building up his knowledge and experience of leadership. He fought in the storming of Chapultepec, showing the boldness that was characteristic of his military style.

After Mexico, Hooker remained in the army for several years but frustrated at not achieving his ambitions, he returned to civilian life in California.

Entering the Fray

When the Civil War began, both sides sought volunteers and men to lead them. It was the opportunity for Hooker to fulfill his thwarted dreams.

He gathered a unit of local volunteers and began drilling them ready to fight for the Union. However, it quickly became apparent that most of the war would be fought in the East.

A generous friend gave Hooker the funds he needed to go to Washington. There he petitioned men of influence, some of them old contacts, to give him a command. He rejected an offer of a position as a regimental commander, believing that he deserved something higher. Eventually, after a decisive encounter with Abraham Lincoln, he gained the backing he needed and was made a brigadier general in the United States Volunteers.

On the Offensive

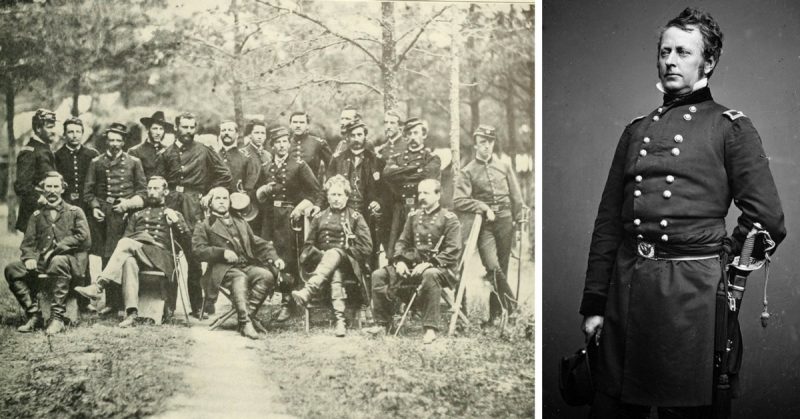

Given command of a brigade and then a division in the Army of the Potomac, Hooker was eager for aggressive action. He bucked against the cautiousness of the men he served under, in particular, General McClellan.

Hooker did well at that level. At Williamsburg, he engaged the rear guard of the retreating Confederate army, throwing his men into the fight rather than waiting for other Union forces to catch up. The result was an indecisive battle which bought the Confederates the time they needed for their retreat. Hooker’s decisive action there won him praise and a promotion to Major General.

Second Bull Run to Fredericksburg

As McClellan continued his inactive approach to the war, Hooker was transferred to the Army of Virginia. There he took part in the Union defeat at the Second Battle of Bull Run. He was made a corps commander.

Returning to the Army of the Potomac, Hooker’s corps led the first assault at the bloody Battle of Antietam. His aggressive leadership inspired his men until an injury took him off the field.

Back at Fredericksburg in December, Hooker again found himself frustrated under Burnside’s lackluster leadership. Despite his best efforts and his men’s losses, the Union army withdrew.

Commander of the Army of the Potomac

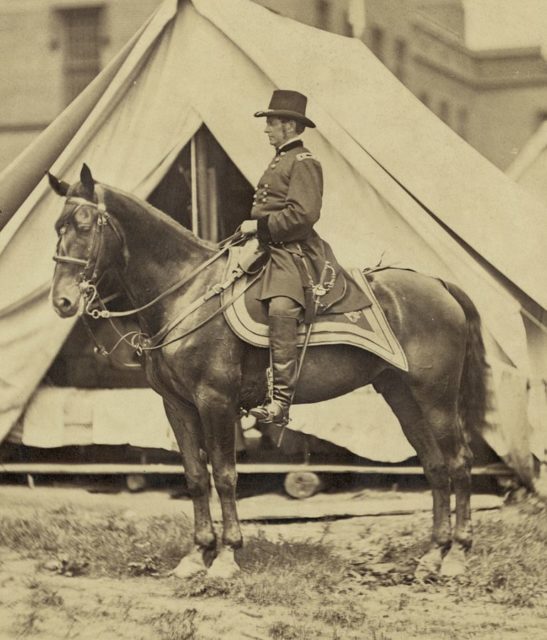

At last, in January 1863, Hooker was put in command of the Army of the Potomac. After two disastrously passive commanders, Lincoln believed he had given the army to a man aggressive enough to get the job done.

Hooker set about reforming an army in trouble. Morale was low and administration inadequate. Fortunately, “Fighting Joe” was the perfect man for the job. His inspiring leadership and care for his troop’s well-being restored their morale. He reformed everything from the quartermaster system to the way units were identified. He brought in leaders he trusted.

At last, Hooker and the Army of the Potomac were ready to go on the offensive.

Chancellorsville

Hooker brought his army into position near a mansion at Chancellorsville, outside Fredericksburg. Outnumbering the Confederates there two to one, it was his chance for victory.

Instead of attacking he waited for Lee to come to them. When Lee attacked on May 1, Hooker had his forces retreat from their advantageous ground. A flanking maneuver by Stonewall Jackson caught him by surprise, and his right flank routed.

The battle was split between two sites nine miles apart – the woods around Chancellorsville and the area around Fredericksburg. On May 3, Hooker ordered John Sedgwick to seize the heights behind Fredericksburg and attack Lee’s rear. His forces, at Chancellorsville, still did not attack.

As the battle raged, a cannonball destroyed the post that Hooker was leaning against. He recovered, but his lost nerve did not return.

Hooker’s passivity allowed Lee to divert most of his forces into an assault on Sedgwick on the heights outside Fredericksburg. Most of Hooker’s commanders wanted to go on the attack; the Union had greater numbers, and half their forces had not yet joined the fight.

However, Hooker had no confidence in himself. He retreated, conceding the battle.

(Apocryphal painting depicts the wounding of Confederate Lt. Gen. Stonewall Jackson on May 2, 1863).

After Command

Within two months, Lincoln removed Hooker from his post as commander of the Army of the Potomac. Hooker was clearly not cut out for the job.

He remained a general, returning to the role of a corps commander. At that level, he once again showed the skill that had led to his promotion. He took part in the battles of Lookout Mountain and Chattanooga and the Atlanta Campaign. His leadership in those actions helped to repair his reputation. However, he remained discontented with the men above him.

After the War

Hooker remained in the army for some time after the war. He took part in the funeral procession for his friend Abraham Lincoln. He married at the age of fifty but ill health bothered him, and he did not have a comfortable retirement. He died in October 1879 at the age of 64.