World War II wasn’t just a conflict of tanks, planes, and soldiers—it was also a battle fought in the shadows of intelligence and counterintelligence. Both the Allies and the Germans depended on espionage and secret operations to gain strategic advantages. While we might think of modern spies equipped with high-tech gadgets, much of the most valuable intelligence during the war was gathered through surprisingly low-tech means. One of the most vital pieces of information for both sides early on was something seemingly simple yet crucial: accurate weather data.

Weather played an important role in World War II

Germany was far behind the Allies

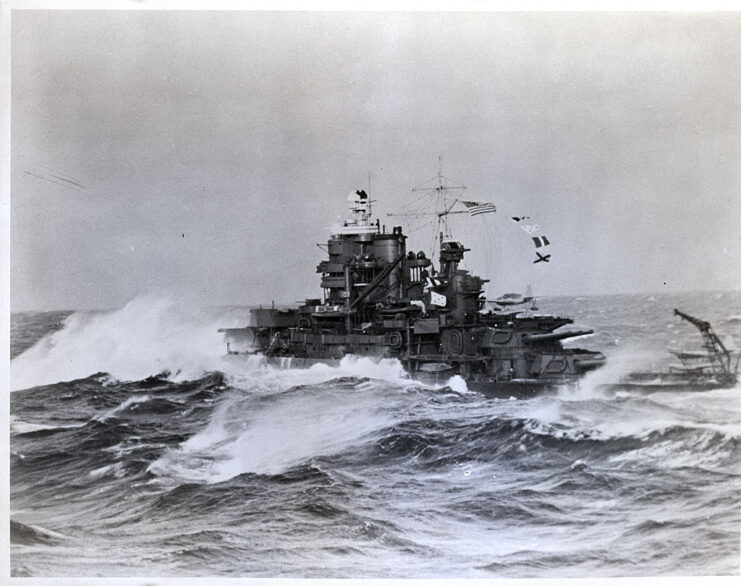

Since the Germans were behind the Allies in the race for meteorological data, they used specially-modified aircraft, ships and U-boats to retrieve weather information. However, these missions proved to be quite dangerous. The Allies would easily destroy or capture a lonely weather vessel, and the aircraft weren’t of much use either.

They needed a way to collect the same amount of data as the Allies, but to do that, the German military needed weather stations on the North American continent: enter the Wetter-Funkgerät Land (WFL).

Wetter-Funkgerät Land

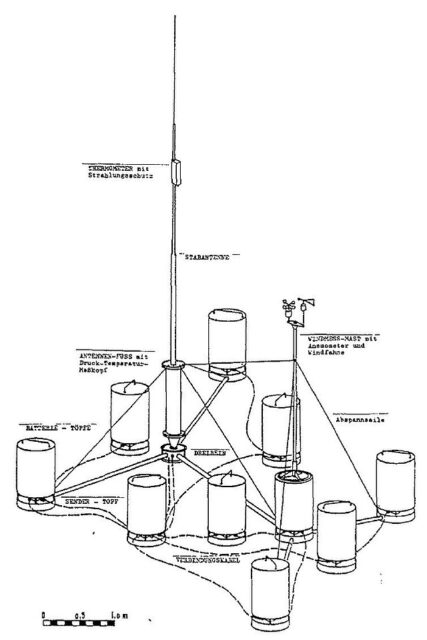

Scientists at Siemens developed an automatic weather station capable of transmitting data every three hours via radio waves on 3940 kHz. Known as the Wetter-Funkgerät Land, twenty-six were manufactured; 14 were placed in Arctic and sub-Arctic regions, including Allied-occupied Greenland, and five were stationed around the Barents Sea. Two were designated for North America.

The WFL featured an array of specialized instruments, including two masts. One of these masts held the anemometer, which measured wind speed and direction. It also included a telemetry device that automatically recorded data and transmitted it via a radio signal. Powered by rechargeable nickel-cadmium batteries, it could operate for up to six months.

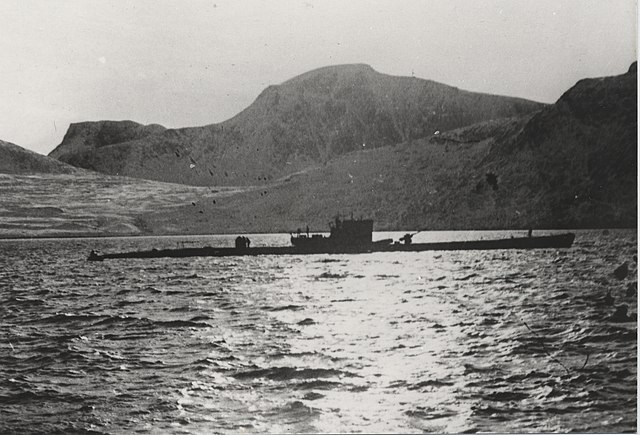

Two U-boats were assigned to install the automatic weather stations in North America. U-537 was the first and only one to successfully deploy the WFL, codenamed “Kurt.” The second, U-867, was sunk in 1944 near the Norwegian coast by a Royal Air Force (RAF) bomber.

Installing the Wetter-Funkgerät Land on North American soil

U-537, under the command of Kapitänleutnant Peter Schrewe, carried two German meteorologists—Dr. Kurt Sommermeyer and Walter Hildebrant—on a mission unlike any other during World War II.

The journey to their destination was treacherous, not because of Allied patrols, but due to harsh Arctic weather. The U-boat encountered a violent storm and collided with an iceberg, causing serious damage. It lost its anti-aircraft gun and suffered a leak in the hull—problems that would have to be addressed once they reached land.

On October 22, 1943, U-537 arrived off the northern coast of Labrador. Captain Schrewe was determined to install the weather station in a remote location, far from any population centers. This was a challenge, as the region was inhabited by the Inuit, who frequently traveled through the remote areas while hunting. The success of the mission depended on keeping the weather station hidden for as long as possible, so Schrewe selected a secluded spot in Martin Bay, at the northeastern tip of the Labrador Peninsula.

Once anchored, a scouting team went ashore to survey the area. Soon after, the meteorologists and several crew members began assembling the 100-kg automatic weather station, known as Wetter-Funkgerät Land. Armed guards were posted around the perimeter to protect the operation from any unexpected visitors. Meanwhile, the rest of U-537’s crew worked on repairing the submarine to prepare for the journey home.

Camouflaging Weather Station Kurt

Weather Station Kurt was disguised with impressive detail. The equipment was marked with the logo and name of a fake organization called the Canadian Meteor Service, and empty American cigarette packs were scattered nearby to make the site look like it had been set up by Allied forces. At the time, civilians weren’t given much information about military operations, so the deception seemed likely to work. German planners also assumed that even lower-ranking Allied military personnel might see the station and ignore it, not wanting to raise questions.

U-537, the submarine that deployed the station, spent just 28 hours on the North American coast before heading back across the Atlantic. Near Grand Banks, Newfoundland, it was attacked three times by Canadian aircraft while being patrolled by sea and air forces. The crew fought off all three attacks and escaped, though they did not sink any enemy ships during the mission. After 70 days at sea, U-537 returned to Lorient in German-occupied France on December 8, 1943.

Becoming a forgotten part of World War II-era history

Weather Station Kurt only worked for a few weeks before failing, and it remained undiscovered long after World War II was over. In 1977, geomorphologist Peter Johnson was conducting research near Martin Bay when he stumbled upon the site. He thought it was a Canadian military outpost and simply marked it as “Martin Bay 7” on the map he kept during his research.

Around that same time, a retired Siemens engineer named Franz Selinger was writing a history of the company. He went through Kurt Sommermeyer’s papers and learned of the station’s existence. He subsequently notified the Canadian Ministry of Defence.

More from us: The Devastating Invasion That Kicked Off the Second World War

In 1981, Weather Station Kurt was officially discovered, standing on the same spot where the Germans had left it over 30 years prior. It was dismantled and taken to the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa, Ontario, where it remains on display to this day.