On the 16th of December 1944, German tanks roared out of the Ardennes forest and smashed into Allied lines. Germany’s last great offensive of the Second World War had begun, and it apparently caught the Allies by surprise.

Allied troops were ill-prepared for what became the Battle of the Bulge. They hadn’t known it was coming. The lines along the Ardennes were not strongly manned. The Germans were able to smash through them, beginning what would eventually become a costly and failed offensive.

Had the Allies really not known what was happening? Or was something else going on?

A Warning Ignored

In early December, Elise Dele, a German-speaking Luxembourger, was smuggled across the battle lines by resistance operatives. Dele had been captured by a German patrol, seen signs of the impending attack, and been questioned by the Germans about what she had seen of American operations. She decided to get out of the way of what was coming and to warn the Allies.

https://youtu.be/bqOPeXLnfF8

In Allied-occupied Luxembourg, Dele talked to the Americans, including a senior intelligence officer of the 28th Infantry Division, about what she had seen.

The news eventually reached Colonel Benjamin Monk Dickson, First Army’s chief intelligencer. Dickson had seen signs of approaching trouble. German agents had been carrying out raids behind Allied lines. Prisoners had talked of a coming offensive. Dickson put the pieces together and concluded that an attack was coming through the Ardennes.

Unfortunately, Dickson had previously drawn inaccurate conclusions, damaging his credibility. His report was ignored. But it wasn’t just Dickson. This was part of a wider pattern.

Pressure in the Ardennes

The Allies had a better intelligence service than the Germans. Between decrypted signals, aerial reconnaissance, and agents on the ground, they had plentiful sources of data. Their experienced analysts had become world leaders in piecing disparate parts together.

For weeks, evidence had been accumulating that the Germans were preparing for a push on the Western Front. Growing numbers of troops, tanks, and planes were appearing. Their concentration in the Ardennes, the scene of a previously successful offensive, implied that an attack was coming. Captured Germans talked about a coming offensive.

Allied commanders found a different way to interpret this evidence. In their view, the troops were being gathered to counter the next Allied thrust, wherever it came. This was a firefighting mission, not an offensive one. There was no need for alarm.

In the aftermath of the Ardennes offensive, the British authorities carried out inquiries into the apparent failure of intelligence that led to this faulty judgment. Their conclusions were that various intelligence sources had been misused, overused, and less effective. Small errors had accumulated into something larger.

In 1968, Major-General Strong, who oversaw intelligence at Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF), published his account of the battle. It was evasive on the course of events.

A Different View

Charles Whiting, who has extensively studied and written about the campaigns on the Western Front, drew a dramatic conclusion. In his book Last Assault, Whiting makes the case that General Eisenhower, as supreme Allied commander, knew about the coming assault. He and his senior commanders put the pieces together then chose not to counter the Ardennes offensive, or even to tell their subordinates that it was on its way.

Whiting’s case depends on indirect evidence. From the 8th to the 10th of November, Eisenhower went to visit the front lines in the Ardennes region. For three days, he talked with commanders along the line, without filing a single message. Neither Eisenhower nor General Bradley, who accompanied him, said anything about this incident in their biographies. But accounts from others indicate that they asked questions about how well the American troops could stand a German attack. There was even discussion of the fact that such an attack would be beneficial, wearing down German resources.

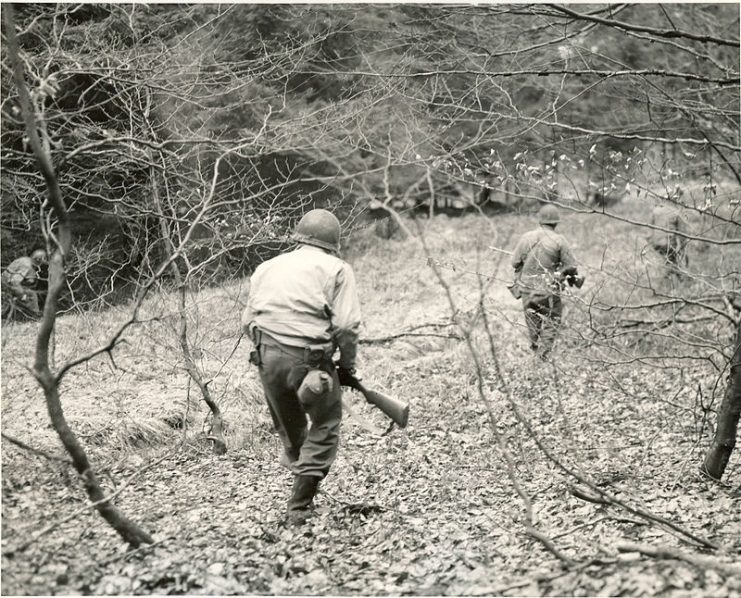

Following this trip, experienced American soldiers were cycled out of the Ardennes, replaced by fresh troops. Over the weeks that followed, information mounted about a planned German attack. Even the locals could see what was coming and took down Allied flags, not wanting to make themselves into targets when the Germans returned.

Eisenhower was ignoring a growing heap of evidence, but why?

Eisenhower’s Trap

By December 1944, the Germans were well dug in along the frontier and fighting hard to hold the Allies back. In the Hurtgen Forest, a whole sector of the Allied advance had stalled. The fighting had become a war of attrition and the Allies weren’t winning.

If the Germans were drawn into the open by launching an advance, then they would expose themselves to attack. This would leave them significantly weaker than they had been, breaking the deadlock.

In the build-up to the Bulge, all Allied armored divisions on the Western Front were disengaged from combat. It was as if they were preparing for a counterattack. But why prepare a counterattack if you don’t know an attack is coming?

If Eisenhower’s plan was to draw the Germans out then it paid off. The Germans attacked, stalled, and were counterattacked with heavy losses. It was a significant step in breaking the stalemate and winning the war.

Cover Up

If Eisenhower had planned such a cunning maneuver, why cover it up?

Because of the sacrifices involved. By deliberately weakening that part of the line and not warning troops there about the attack, Eisenhower sacrificed many of their lives for a greater goal. It wasn’t an acceptable thing for an American commander to admit to. For a man whose ambitions would one day take him to the White House, it would have been political suicide.

Perhaps Whiting underestimates Eisenhower’s conscience and overestimates his cunning. But whether through incompetence or brutal strategy, the Allies ignored huge evidence that the German attack was coming.

The Battle of the Bulge should never have been a surprise.