The Battle of the Atlantic stands as the longest continuous campaign of the Second World War. During this time, the German Kriegsmarine dominated the mid-Atlantic, deploying U-boats to torpedo merchant vessels and passenger liners. Determined to protect vital transatlantic shipping routes, the Allies began exploring an unusual solution—an ambitious idea known as Project Habakkuk.

Steel and aluminum were in short supply

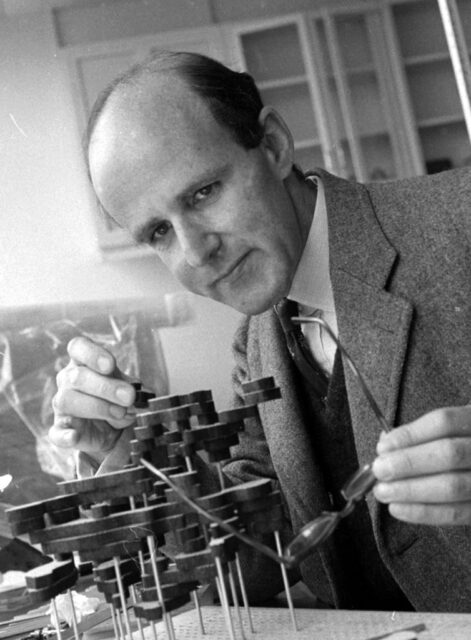

Project Habakkuk came from the mind of scientist Geoffrey Pyke. He was considered a brilliant mind who had support of Prime Minister Winston Churchill, Admiral of the Fleet Lord Mountbatten and Irish scientist J.D. Bernal.

Pyke came up with the idea for the aircraft carrier during a visit to the United States, during which he organized the production of M29 Weasels for Project Plough. He’d been in search of a cheap and effective way to protect vessels that were well out of reach of Royal Air Force (RAF) patrols, as steel and aluminum were in short supply. His answer: ice.

Constructing an aircraft carrier out of ice

According to Geoffrey Pyke, ice could be manufactured with one percent of the energy needed to produce an equivalent mass of steel. As it was considered virtually indestructible at the time, he proposed that an iceberg – natural or artificially made – should be leveled on top to create a runway and hollowed out to allow for storage.

The unique aircraft carrier would be nearly 2,000 feet long by several-hundred feet wide, with a draft of 150 feet. If everything went according to plan, the vessel could carry 100 twin-engine bombers and 200 fighter aircraft.

Wood pulp is thrown into the mix

Winston Churchill was enthusiastic about the proposal and wanted work to start on the aircraft carrier immediately. Toward the beginning of 1942, Geoffrey Pyke and J.D. Bernal asked molecular biologist Max Perutz if such a ship could withstand the conditions of the Atlantic. Perutz, with his knowledge of ice and glaciers, explained that natural icebergs have a tendency to roll over without warning. They’d also be too small for an airstrip.

To create a more stable vessel, Pyke decided to use Pykrete, a mixture of 14 percent wood pulp and 86 percent water. It could be machined like wood and cast into shapes like metal, and would create an insulating shell when placed in water. With wood providing reinforcement and ice acting like steel rebar, Pyke claimed it was stronger and more bulletproof than regular ice. There was also the added bonus that it would melt slower and not sink.

Max Perutz points out another potential issue

Despite Geoffrey Pike’s enthusiasm, Max Perutz pointed out that issues were likely to arise if the Pykrete wasn’t cooled to -16 degrees Celsius. To work through these deficiencies, he conducted several experiments in London, United Kingdom.

Perutz surmised that the aircraft carrier could be built out of the mixture only if the surface was protected by insulation. The vessel would need an onboard refrigeration system and ducts to ensure the temperature was evenly distributed.

Moving work on Project Habakkuk to Canada

Neither the United States, nor the Royal Navy wanted to take part in Project Habakkuk, so it was decided a prototype would be constructed at Patricia Lake in Jasper National Park, Alberta, Canada. The ice blocks would be produced at nearby Lake Louise, and the construction would be done by conscientious objectors from Canada.

Geoffrey Pyke assured Winston Churchill that the aircraft carrier could be built in as little as 14 days and would be completed by 1944. The British prime minister ordered a single ship, with a promise of more if the first was successful.

While the initial cost of production was slated to be £700,000, it quickly ballooned to £2.5 million. The Canadians also thought it impractical to build the ship during the spring, with the warmer weather ahead. Paired with Max Perutz’s concerns, it soon came apparent to Pyke and J.D. Bernal that they couldn’t meet the 1944 deadline.

Increasing demands for Project Habakkuk

As development continued, expectations for the proposed aircraft carrier grew increasingly ambitious. The Royal Navy required a vessel capable of traveling 7,000 miles, featuring a hull resistant to torpedoes and sturdy enough to endure rough seas. They also insisted on adding a traditional rudder for steering, abandoning the original concept of using motors to guide the ship. This created a major design challenge, as the rudder would have needed to stand nearly 100 feet tall—a problem engineers were never able to solve.

With complications piling up, naval architects set to work drawing up three alternatives of the original Project Habakkuk concept. Their proposals were presented in August 1943. Although many favored the second option, none proved entirely satisfactory.

Lord Mountbatten withdraws his support

The growing list of concerns eventually led to the abandonment of Project Habakkuk. Construction would be too costly, and it was also found that the amount of material needed would be more than an entire fleet of regular aircraft carriers.

Lord Mountbatten eventually withdrew his support for the project. His reasoning surrounded outside events that had taken place during the carrier’s construction. Portugal had allowed the British to use its airfields in the Azores, and long-range aircraft had been introduced. As well, the Royal Navy had begun escorting merchant ships across the Atlantic, in the hopes of protecting them from German U-boats.

What became of the aircraft carrier built for Project Habakkuk?

In December 1943, a final meeting was held, during which it was concluded that “the large Habakkuk II made of pykrete has been found to be impractical because of the enormous production resources required and technical difficulties involved.”

The prototype aircraft carrier took three summers to completely melt, with the metal components coming to rest at the bottom of Patricia Lake.